It was once said of Coach John “Whitey” Piurek:

“Those young men who have played for and survived Whitey will tell you it wasn’t easy. But eventually they realize that they’ve become better men because of the experience.”

Piurek was a significant New England sports figure due to his contributions as a player, coach, official, scout, and administrator. He’s the only Connecticut coach to win state titles in three different sports. Over a career spanning a half century, he earned state, regional and national recognition for his dedication to high school athletics, particularly in baseball, football and basketball. His life and career reflected a deep commitment to the values of discipline, hard work and respect for the game.

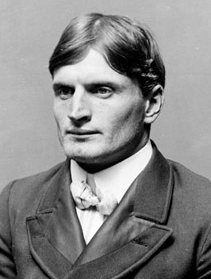

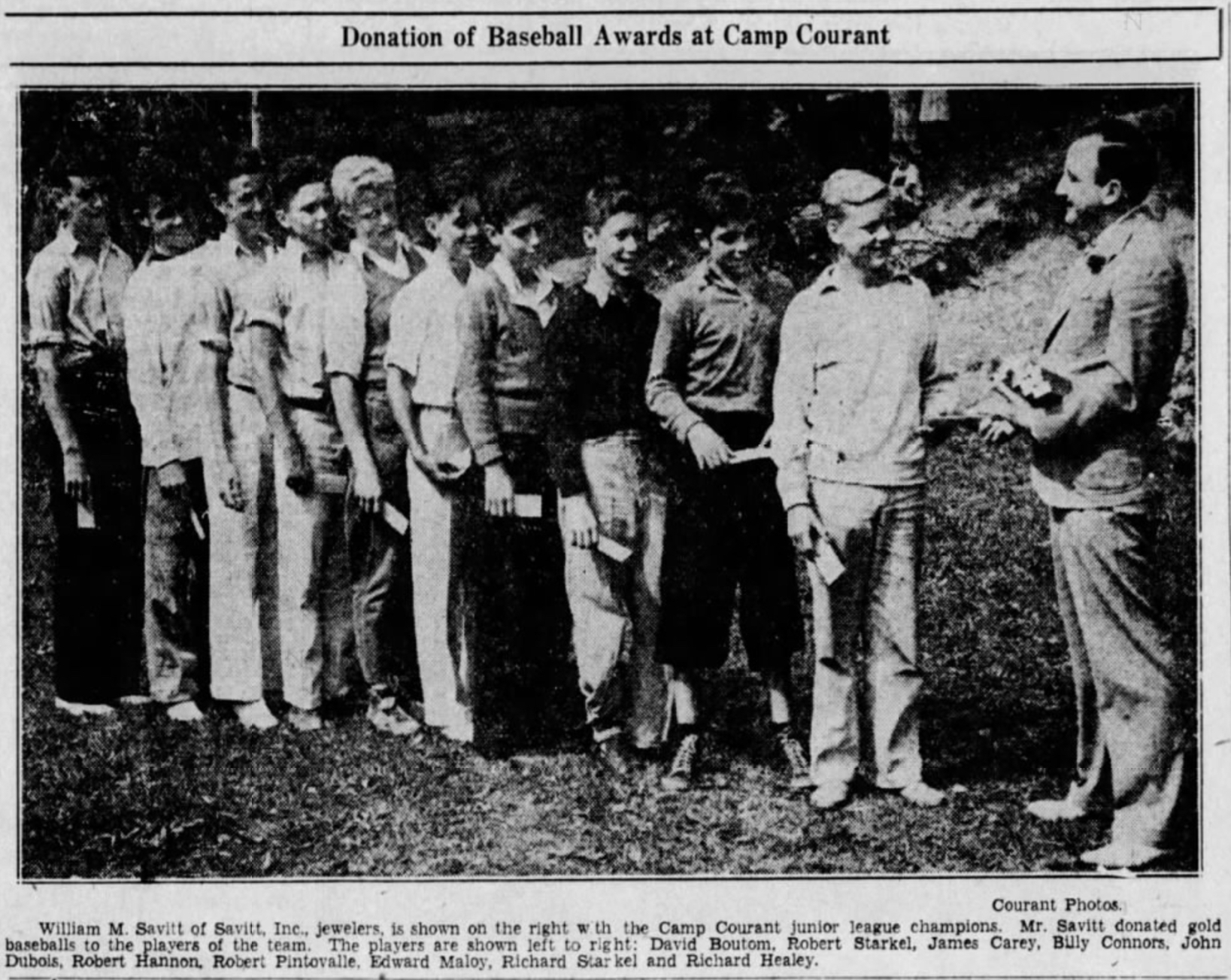

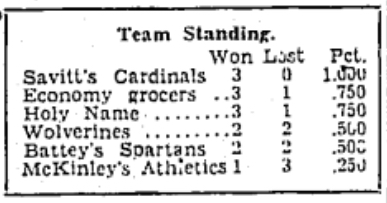

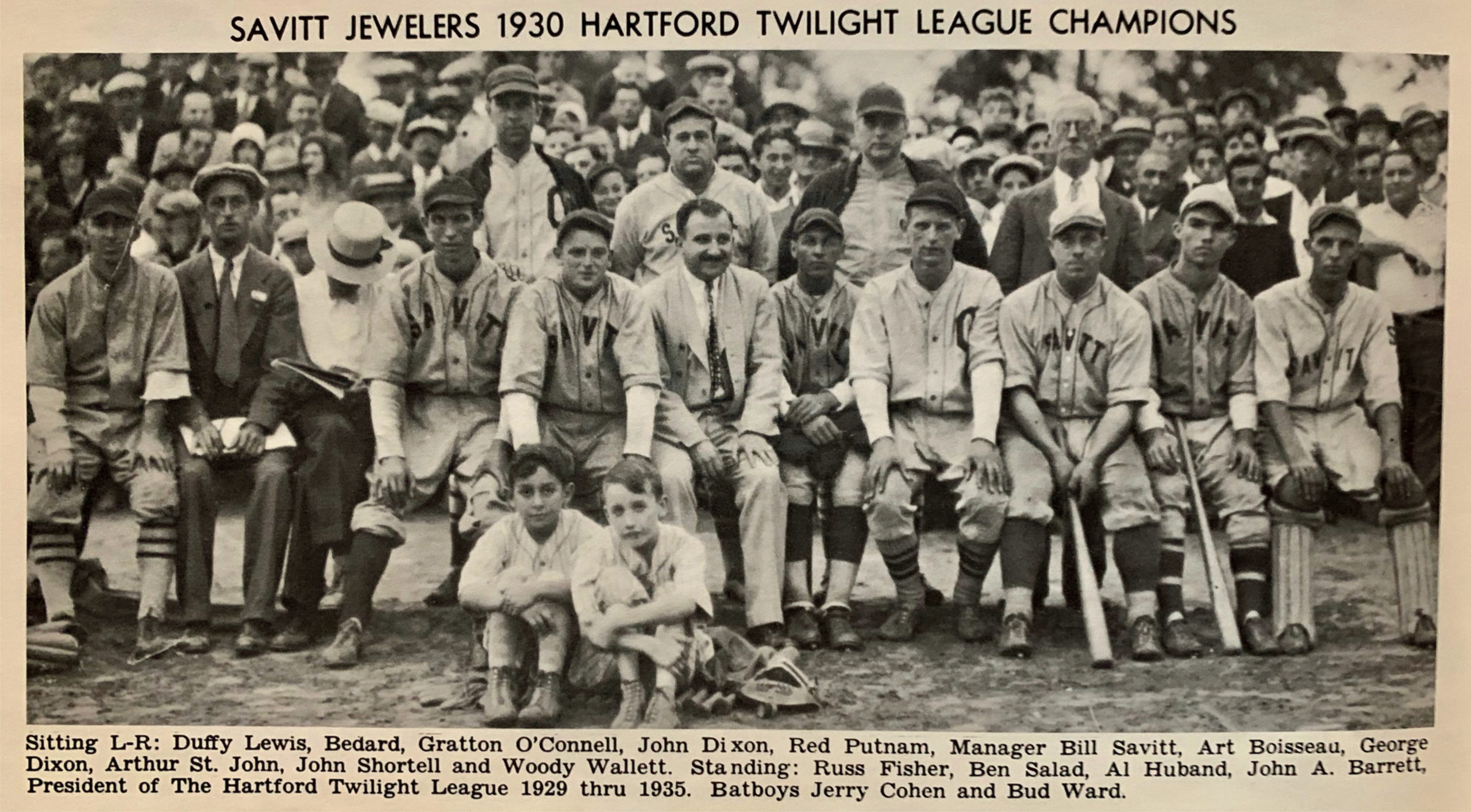

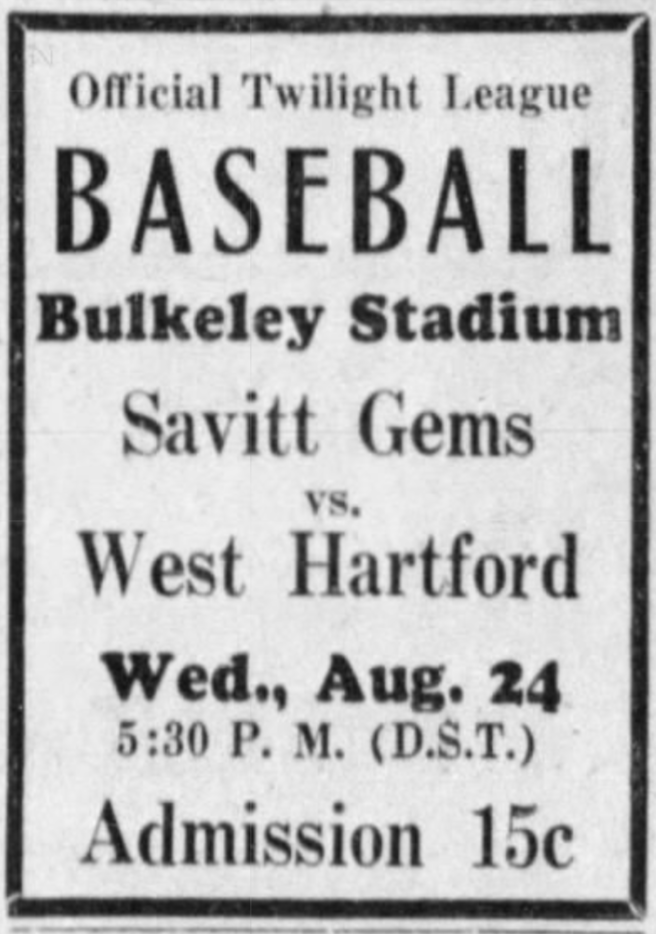

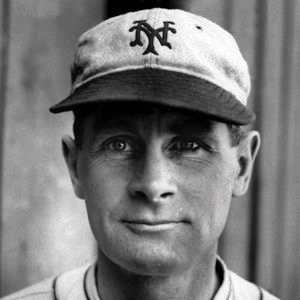

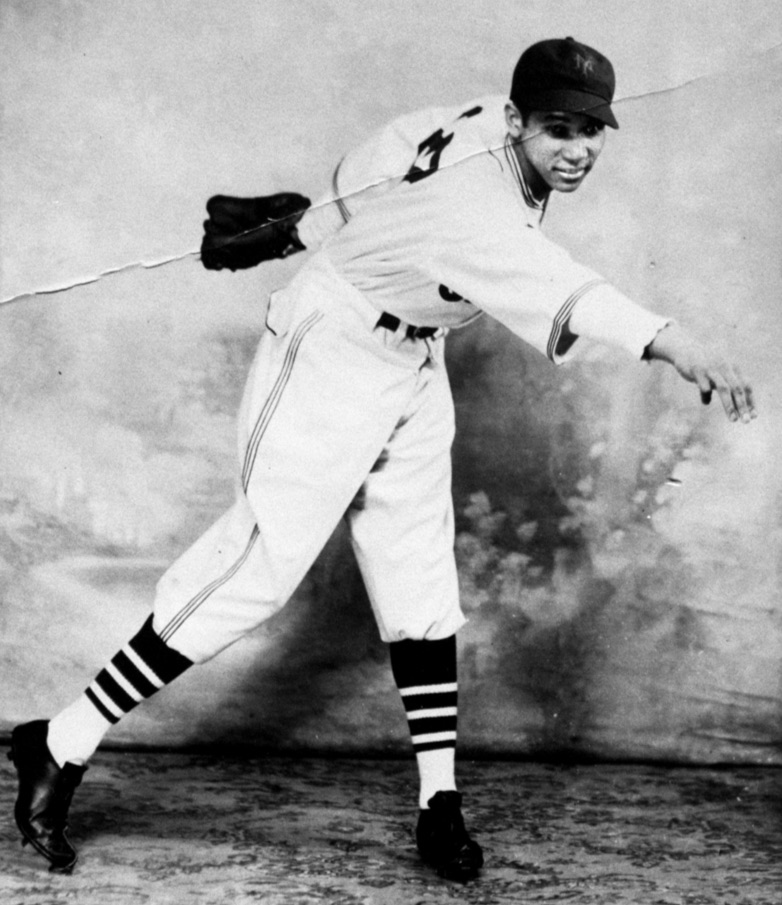

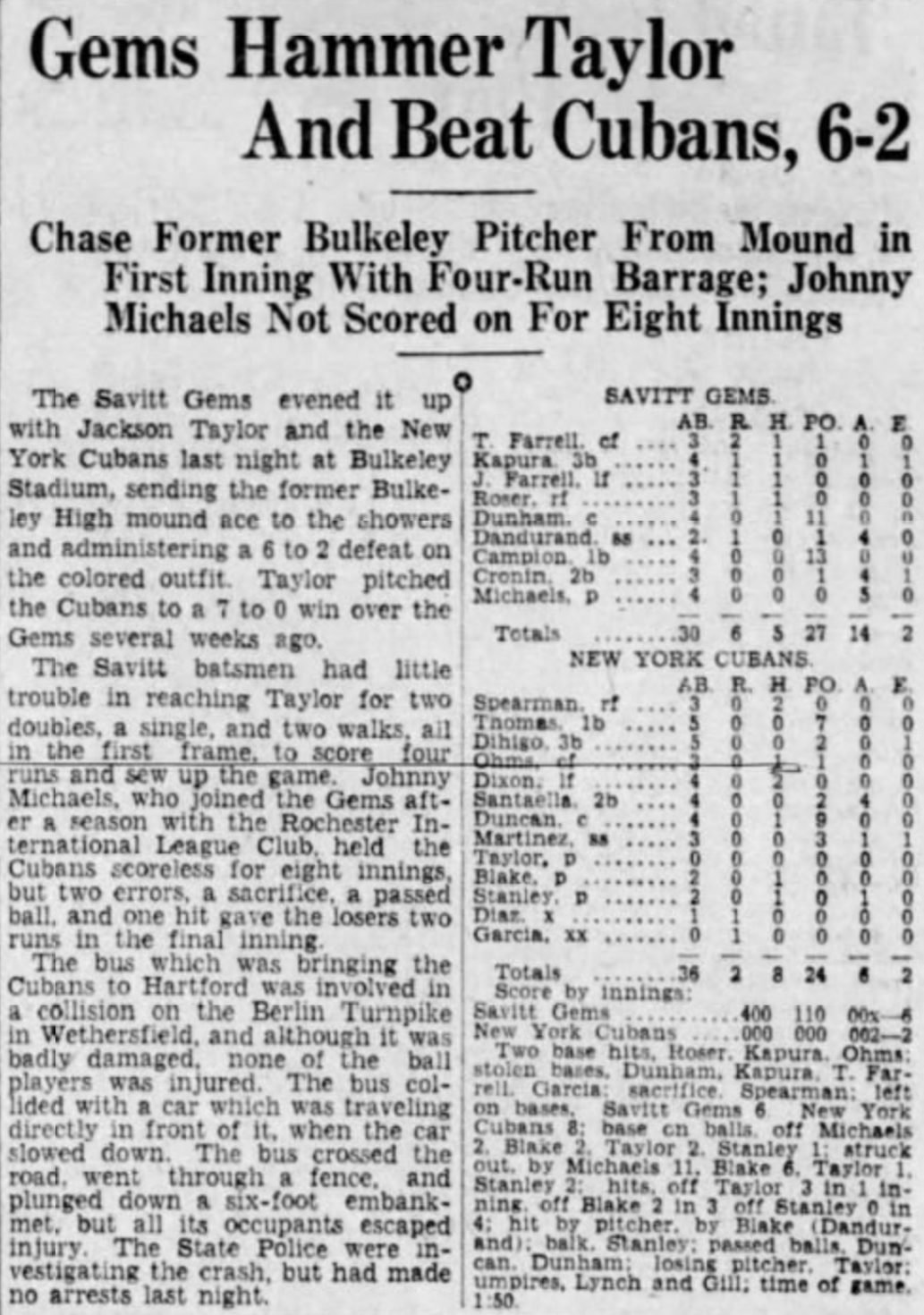

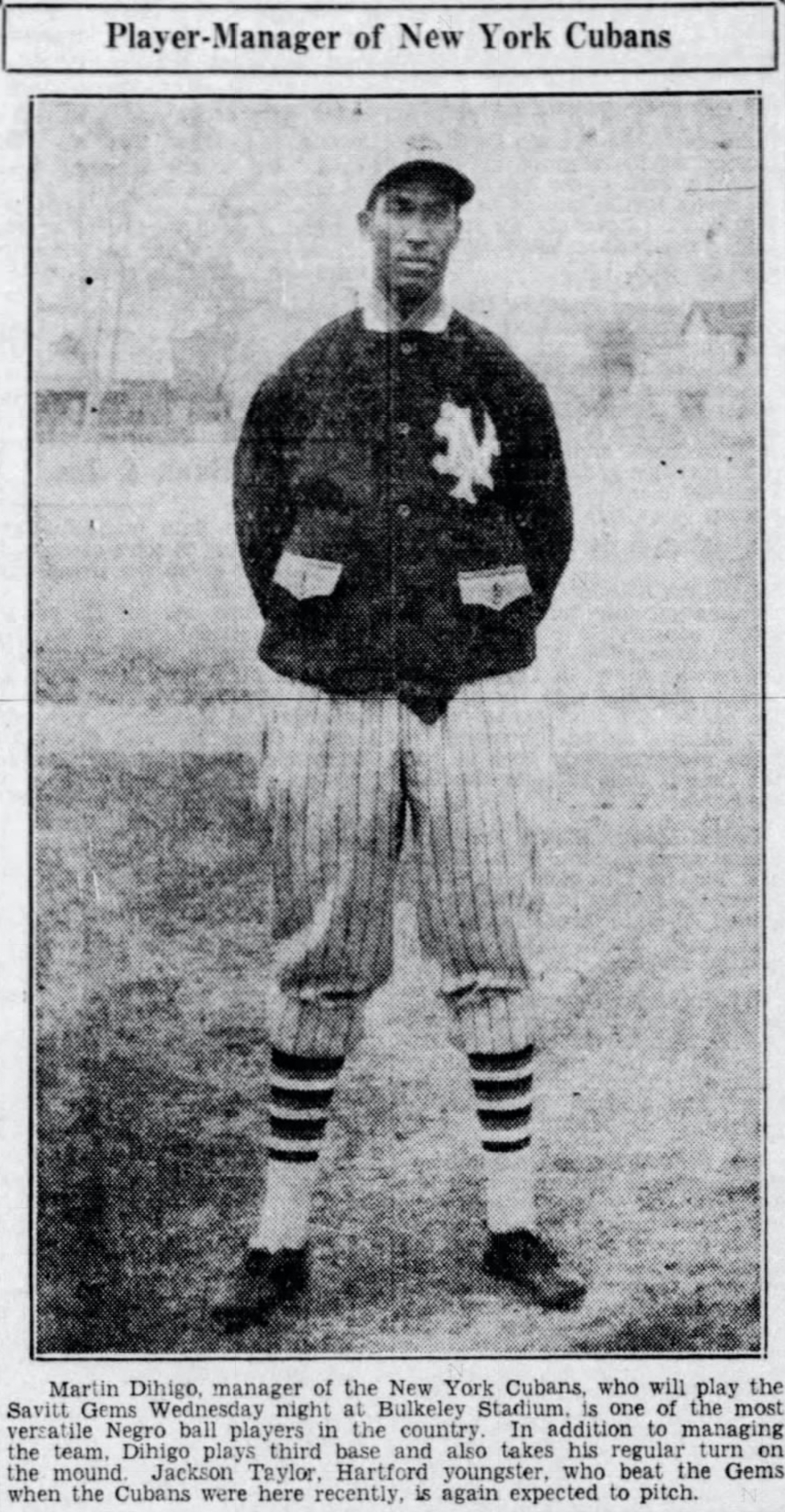

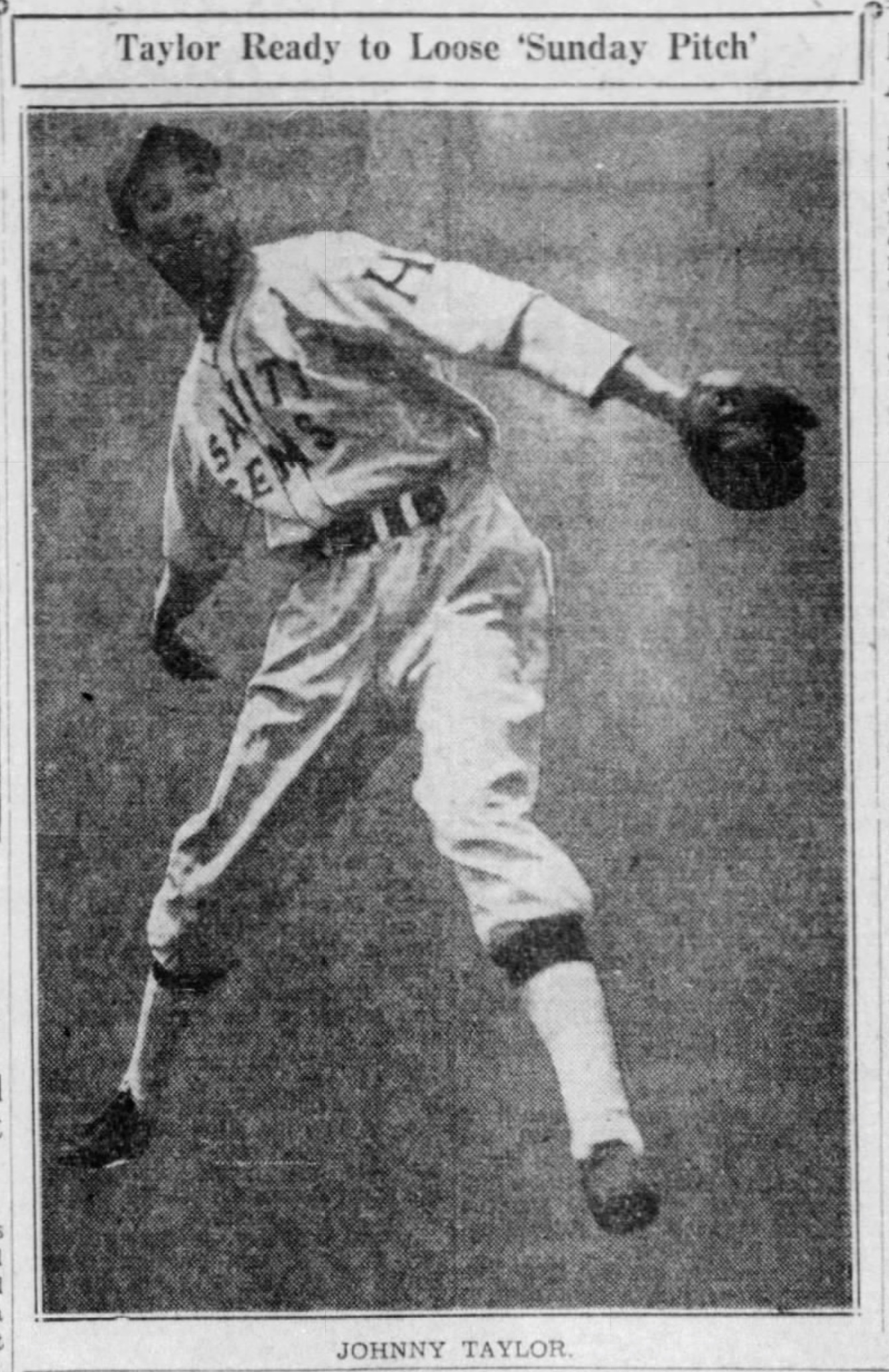

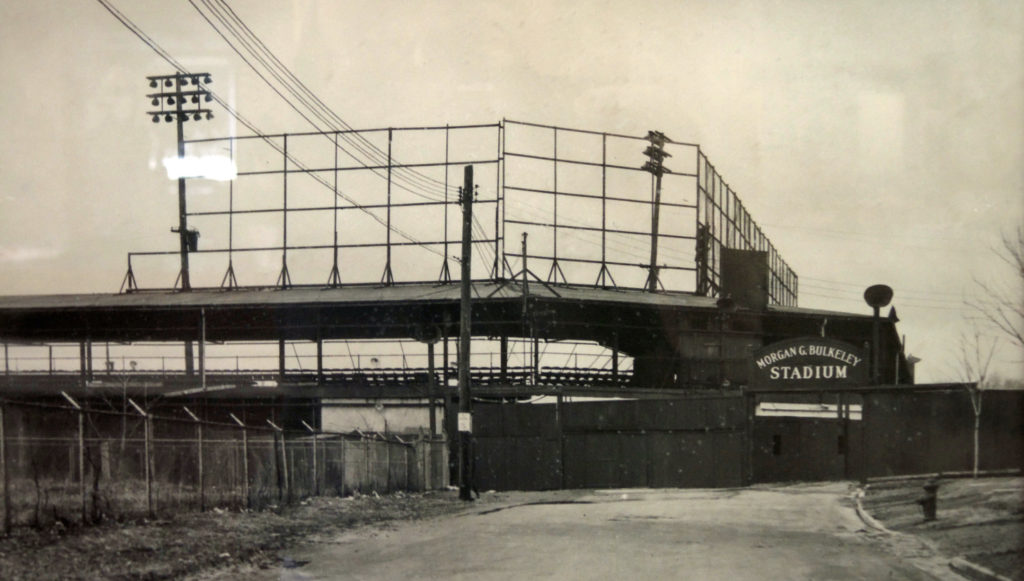

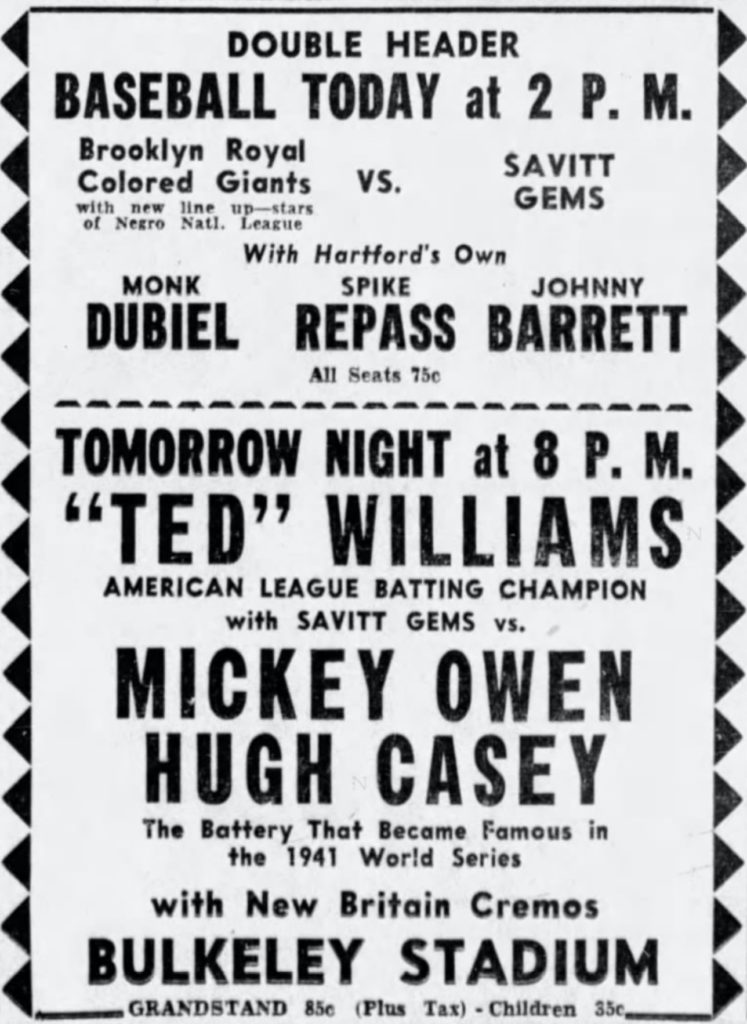

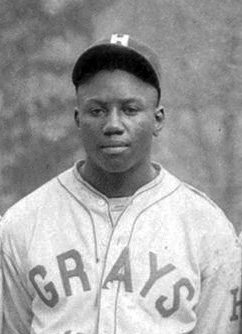

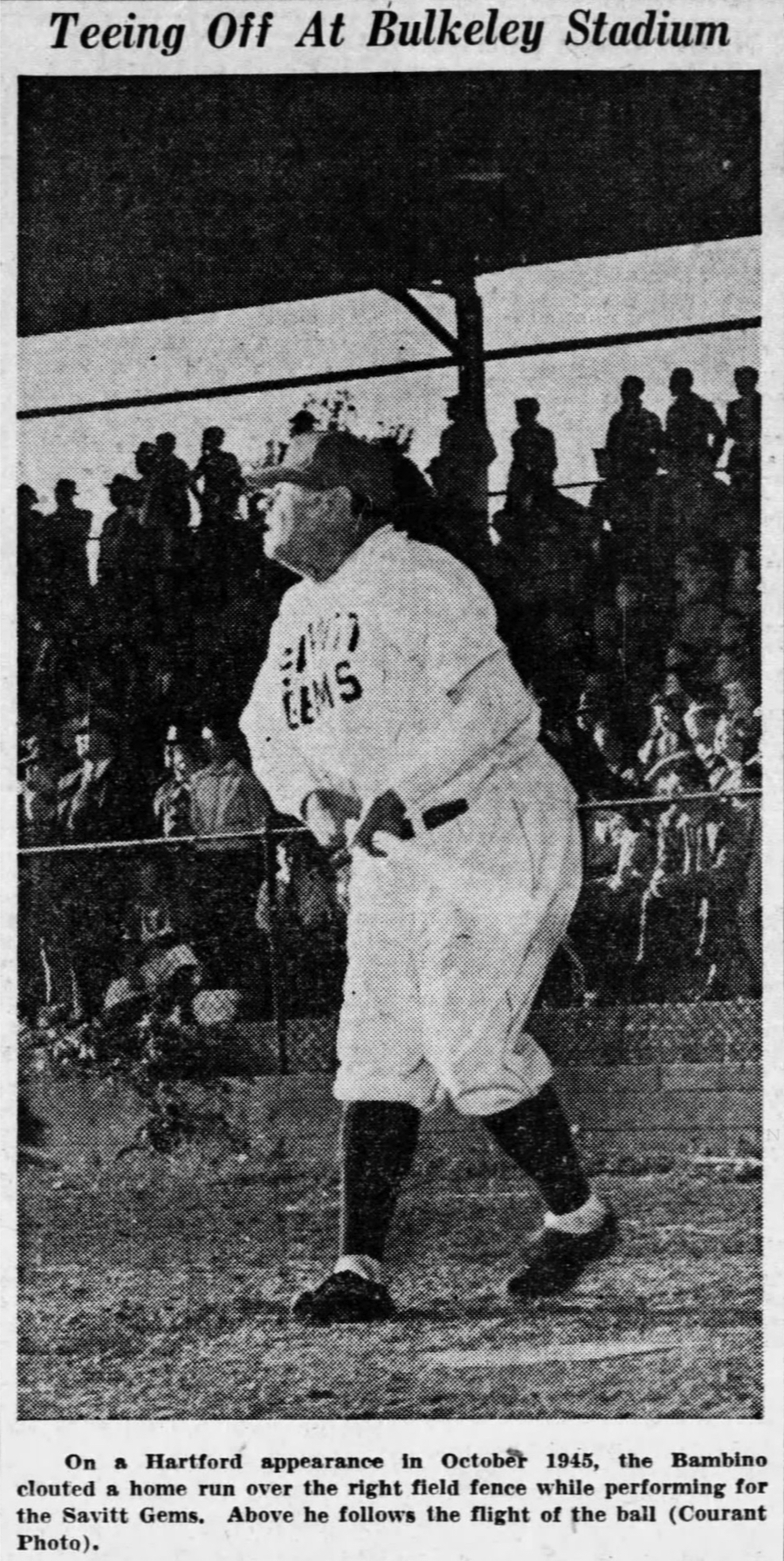

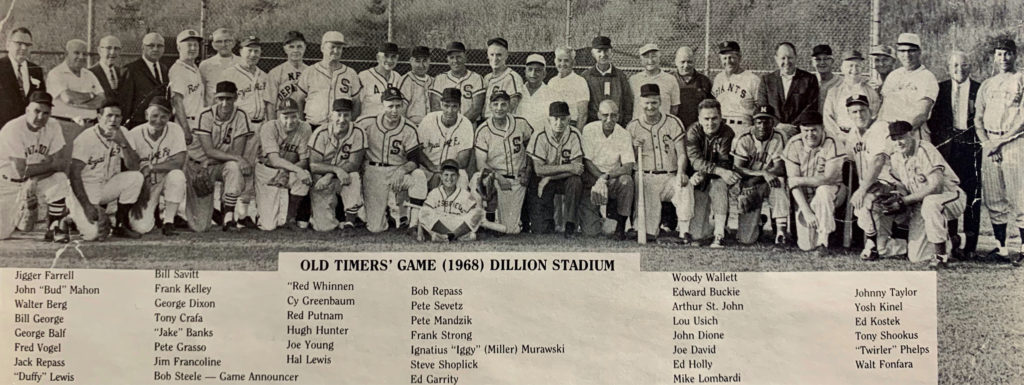

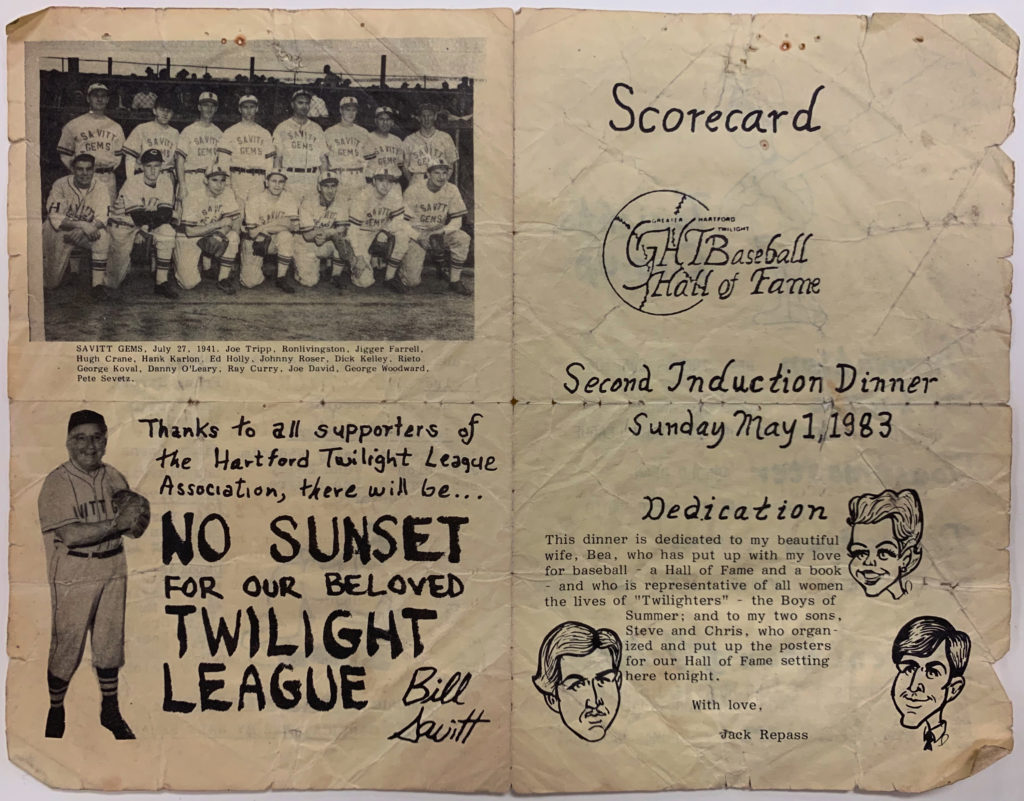

Piurek was born on June 11, 1915, in Enfield, Connecticut. He excelled in multiple sports as a youngster at Hartford’s Bulkeley High School. He was a speedy shortstop for the Maroons under the legendary head coach, Babe Allen. His teammates included two of Hartford’s greatest ballplayers, Johnny Taylor and Bob “Spike” Repass. Piurek graduated from Bulkeley as valedictorian of the Class of 1935. That same year, he competed in the Hartford Twilight League with a club known as Check Bread. Hartford Courant reporters called him, “a natural” and “one of the most promising schoolboy baseball players ever to step into spiked shoes in this state.”

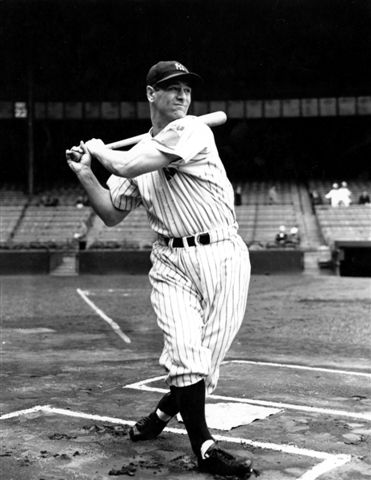

Piurek attended Holy Cross College, where he joined a top-rated program coached by Jack Barry – a Meriden native formerly of the Million Dollar Infield. Barry chose Piurek to be captain of the Crusaders and he became a highly scouted shortstop and first baseman. He was selected to play in the Cape Cod Baseball League and snatched all-star honors with the Harwich Mariners. After receiving Dean’s List honors, a bachelor’s degree from Holy Cross, and a masters degree from Catholic University, Piurek pursued professional baseball.

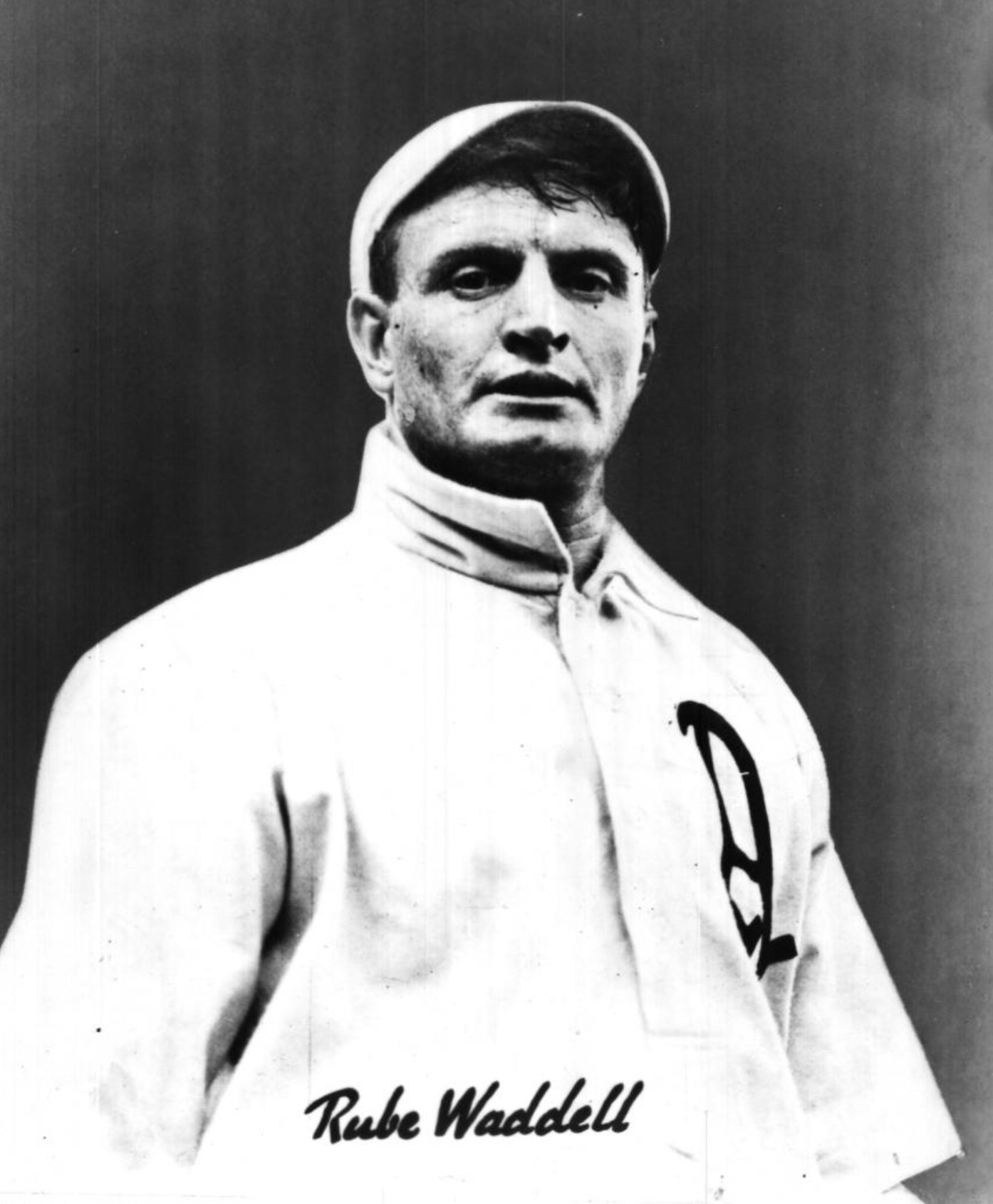

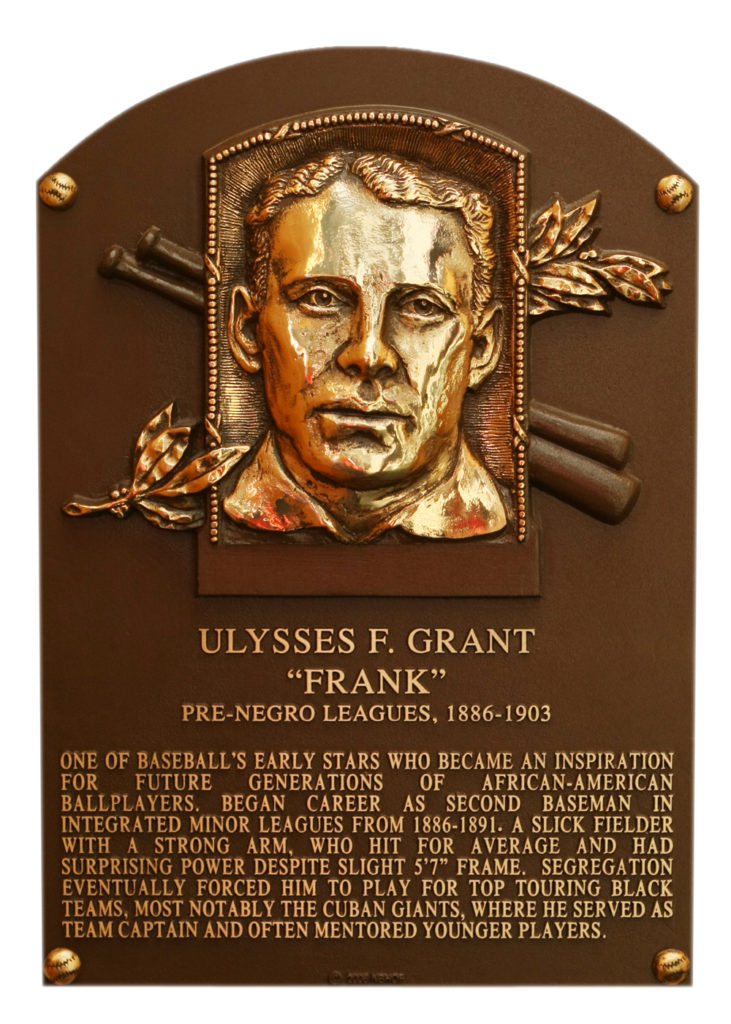

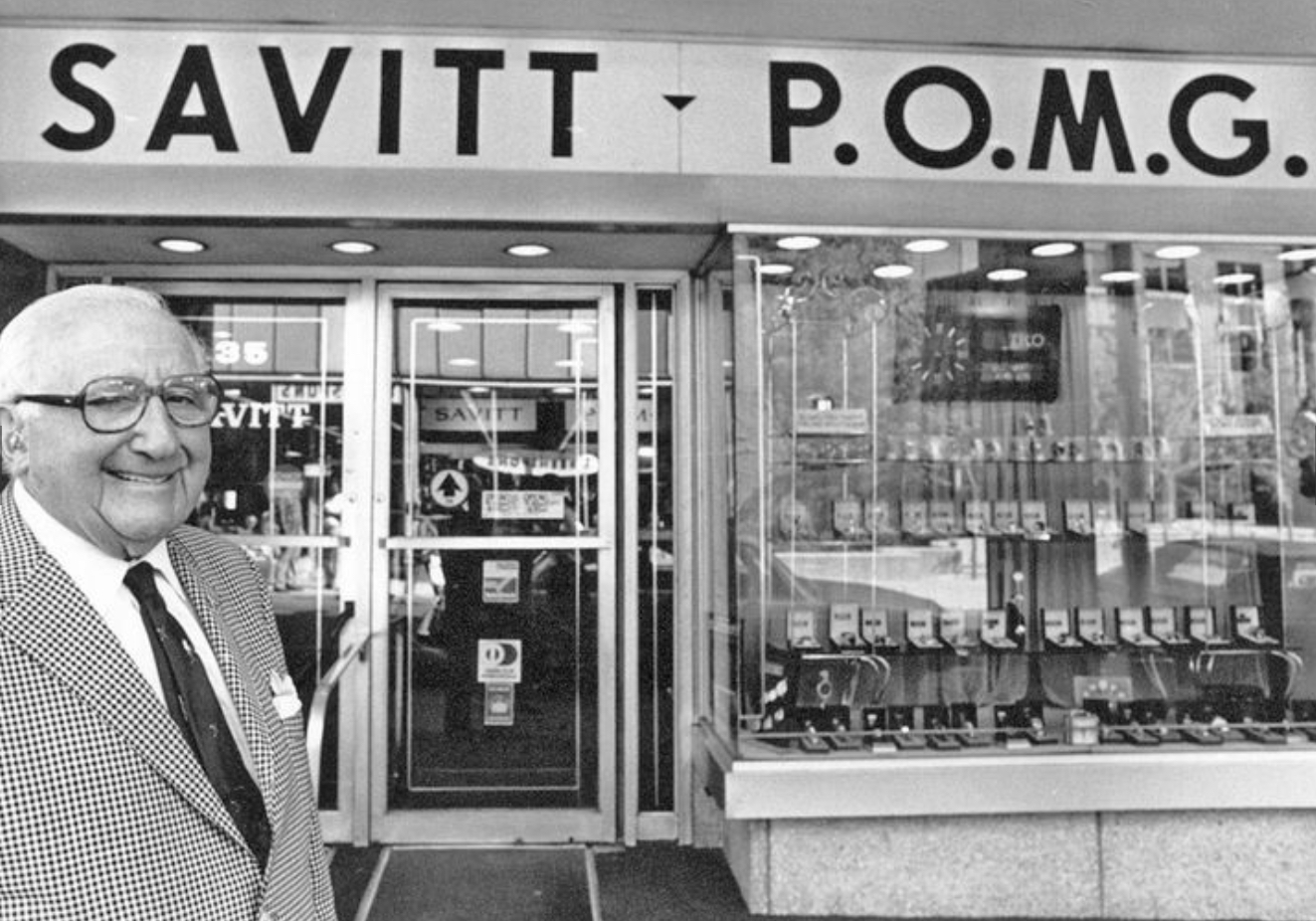

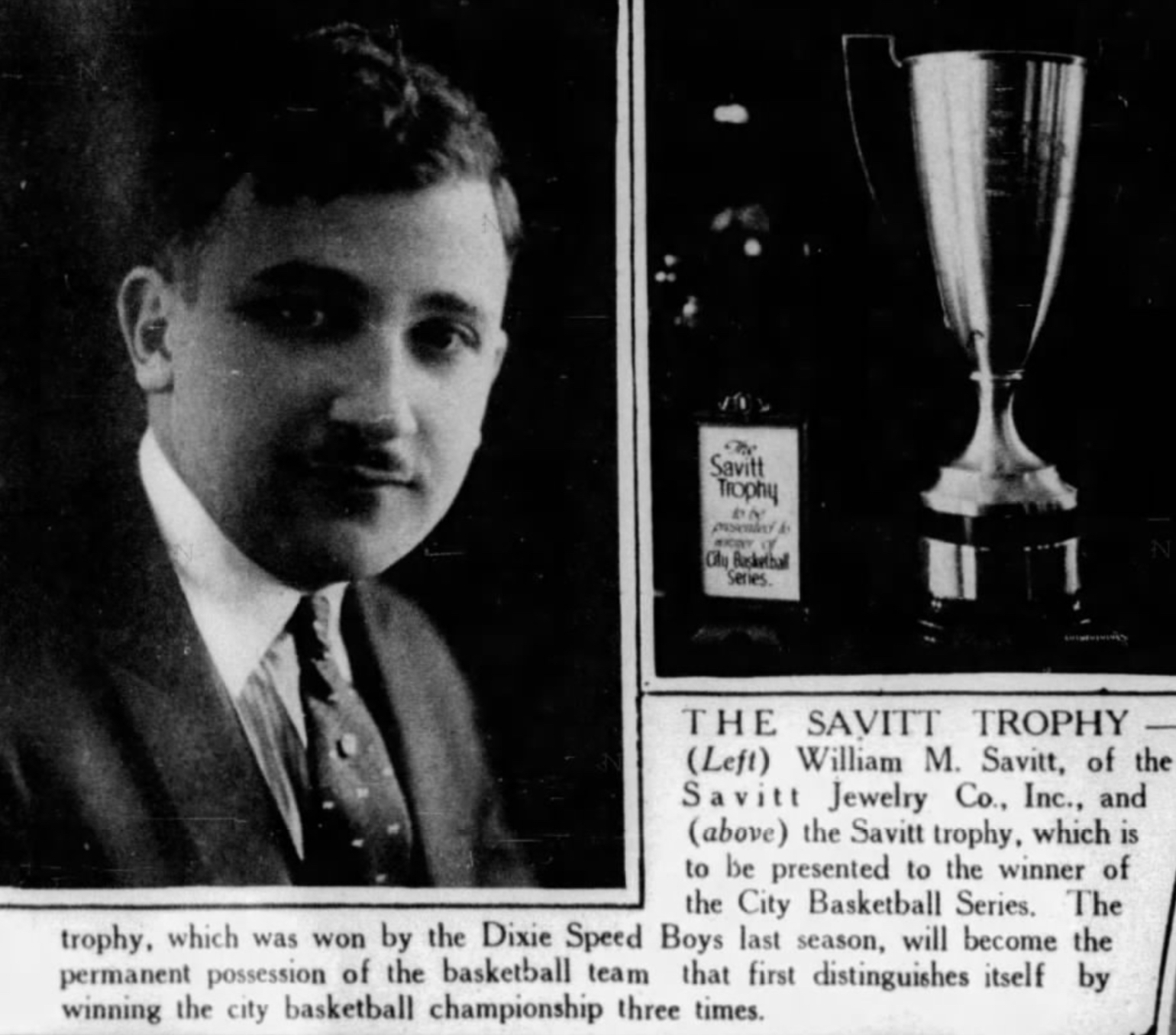

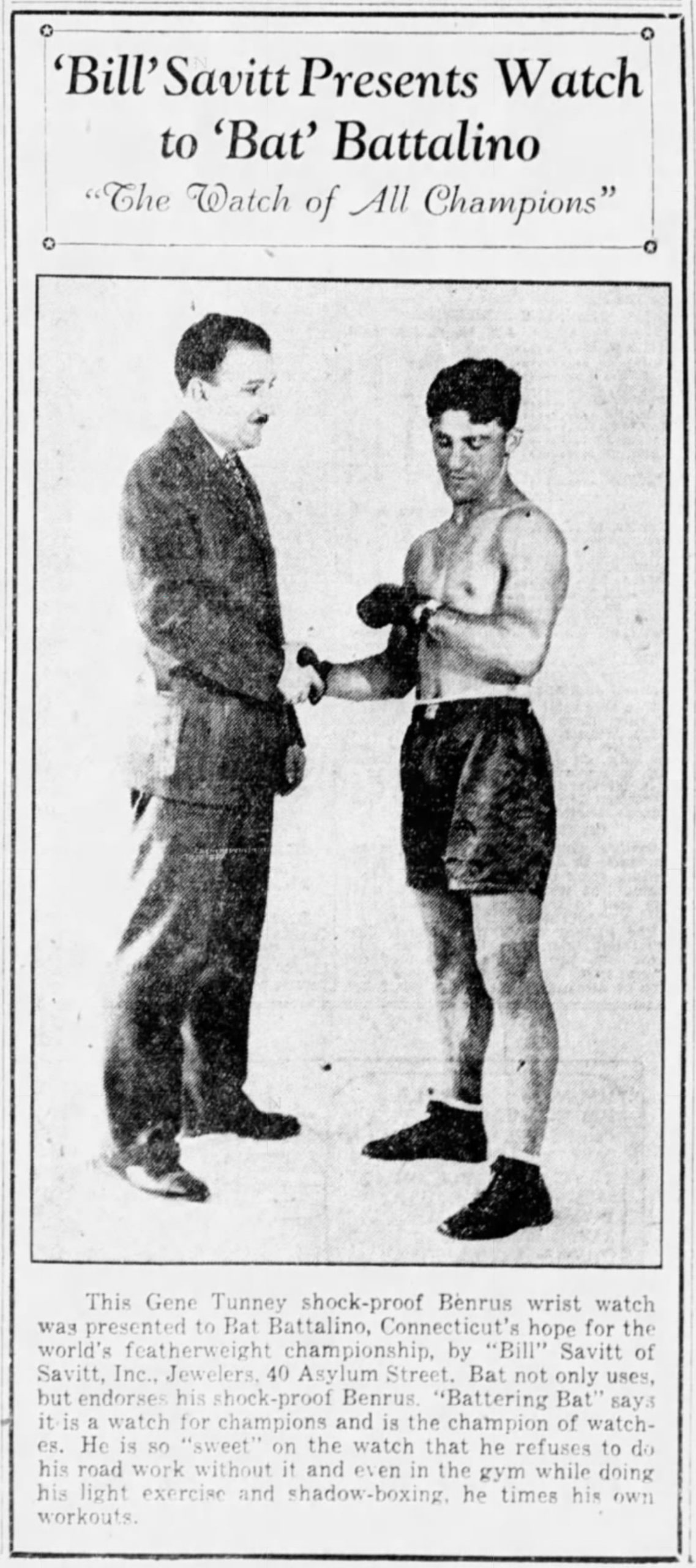

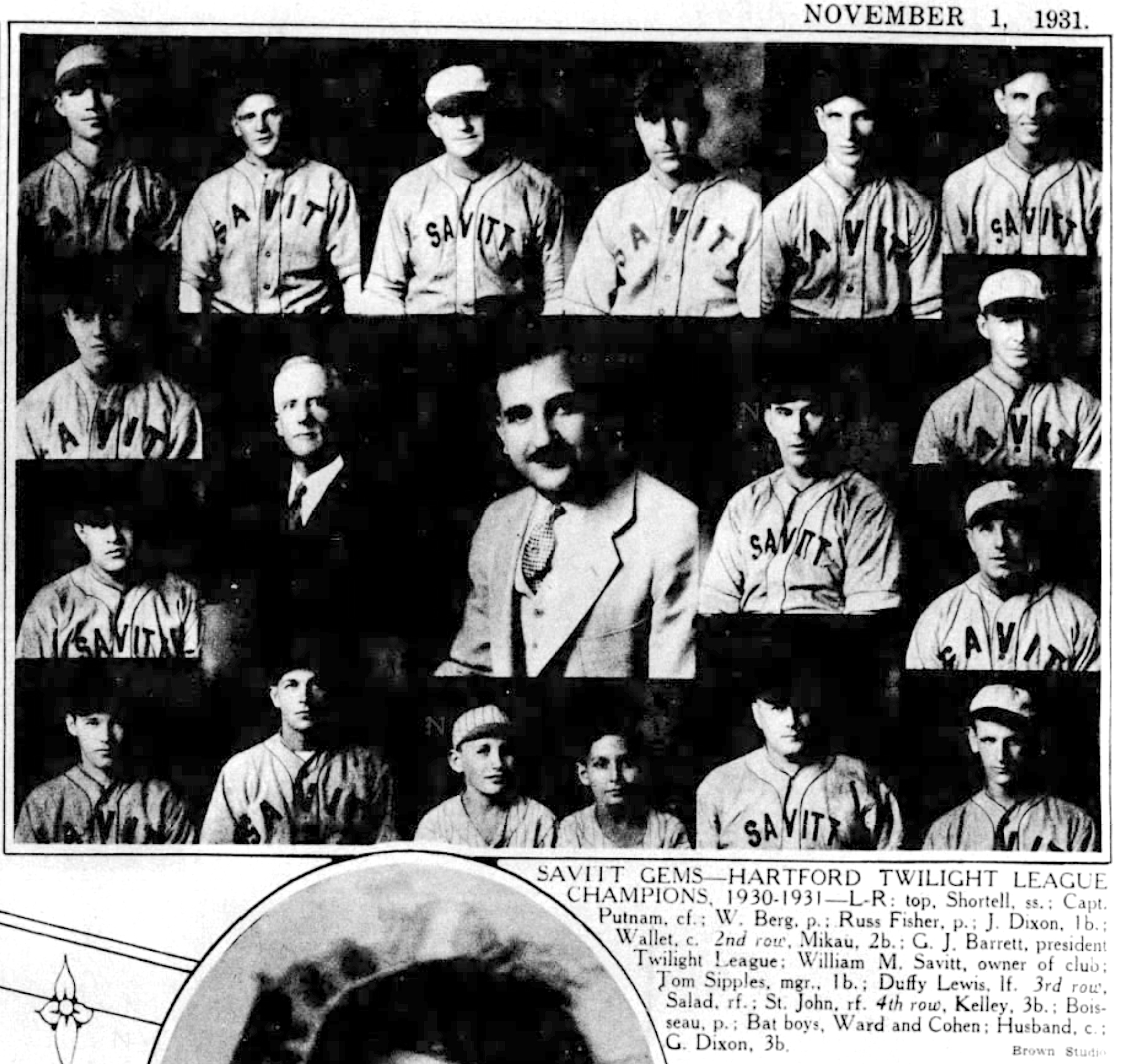

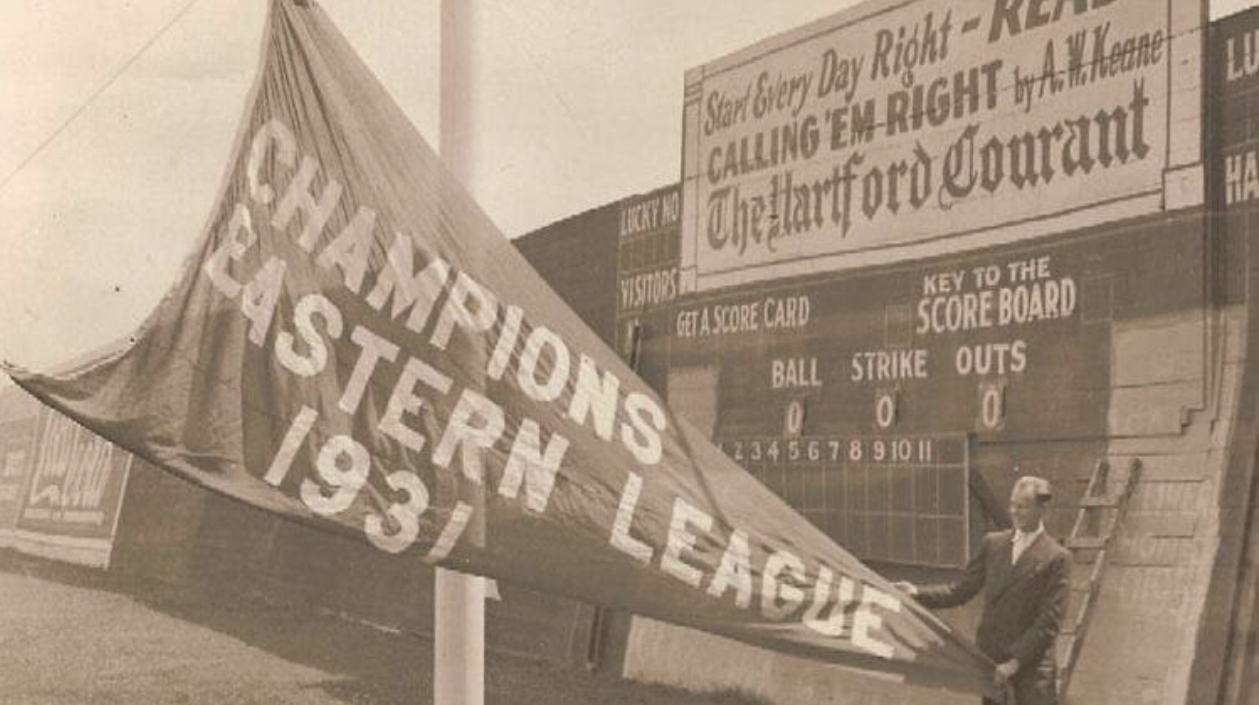

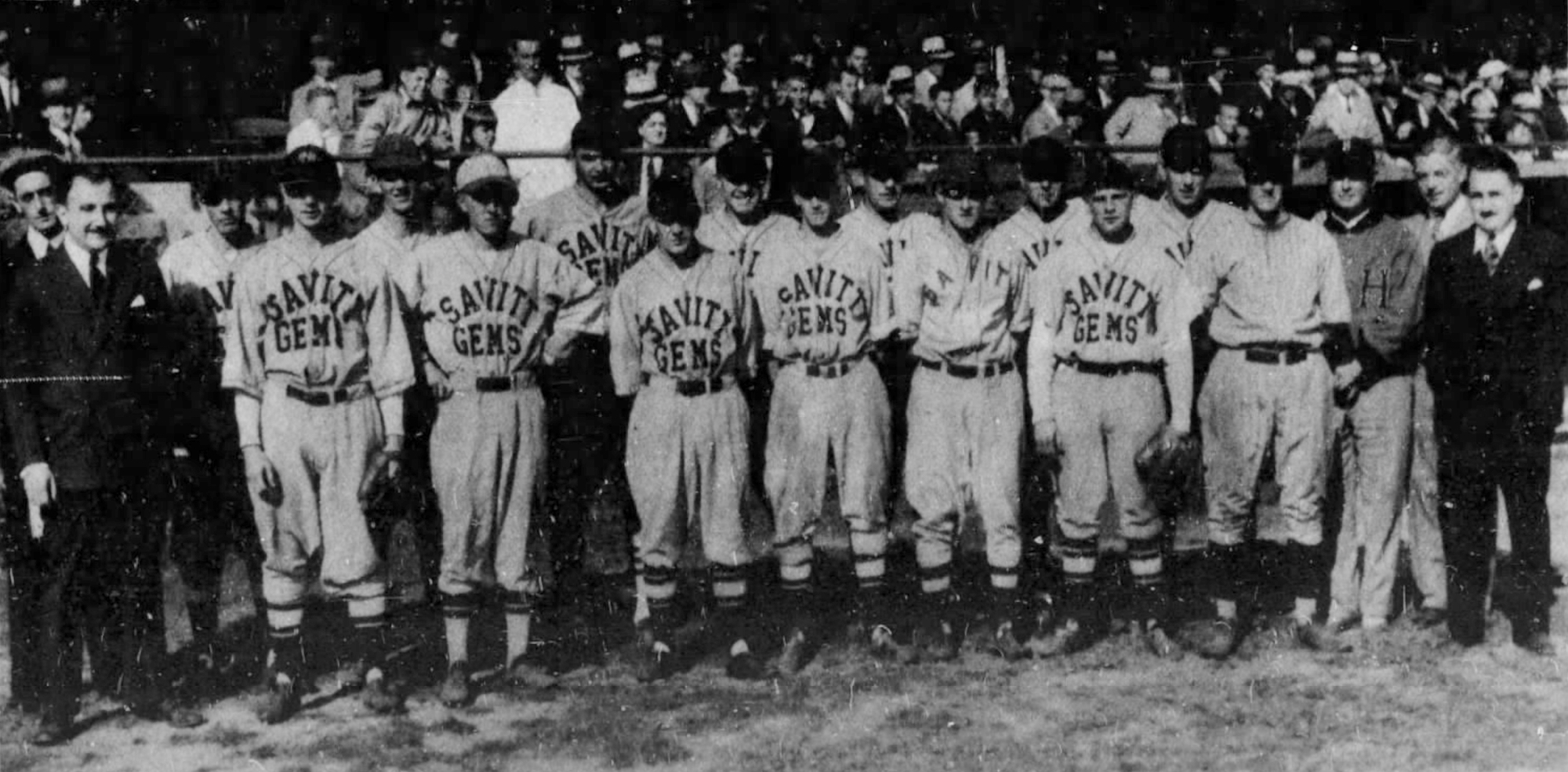

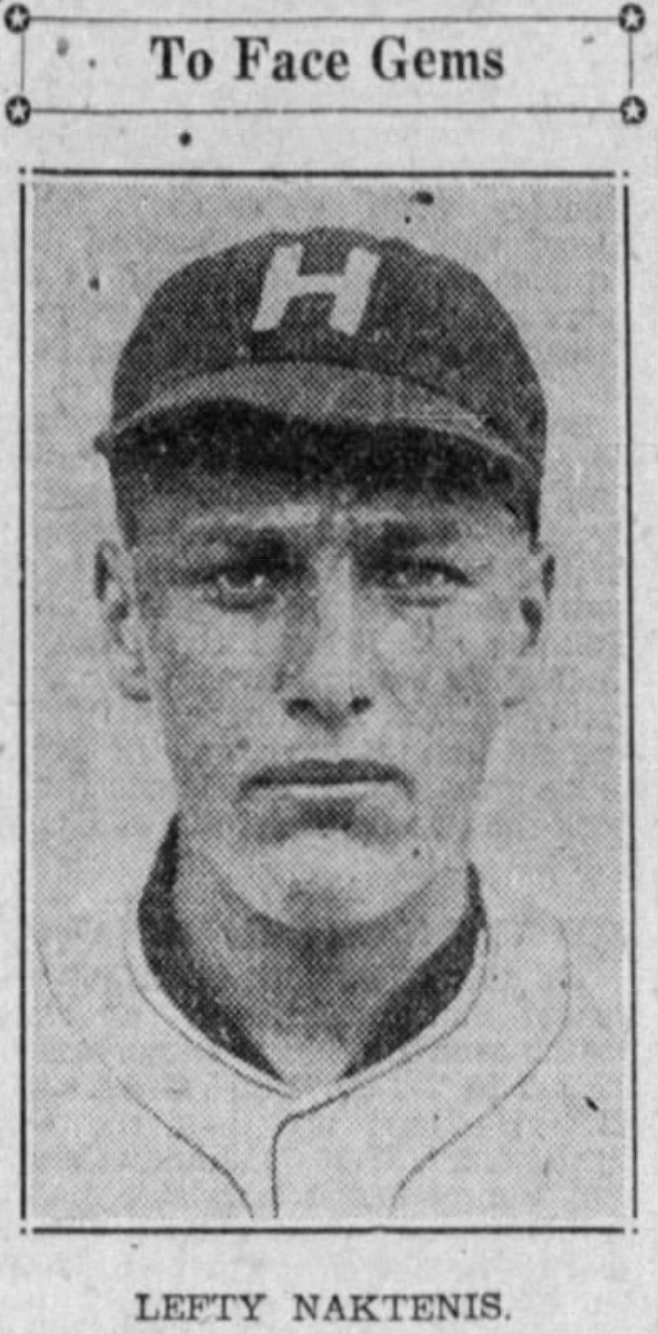

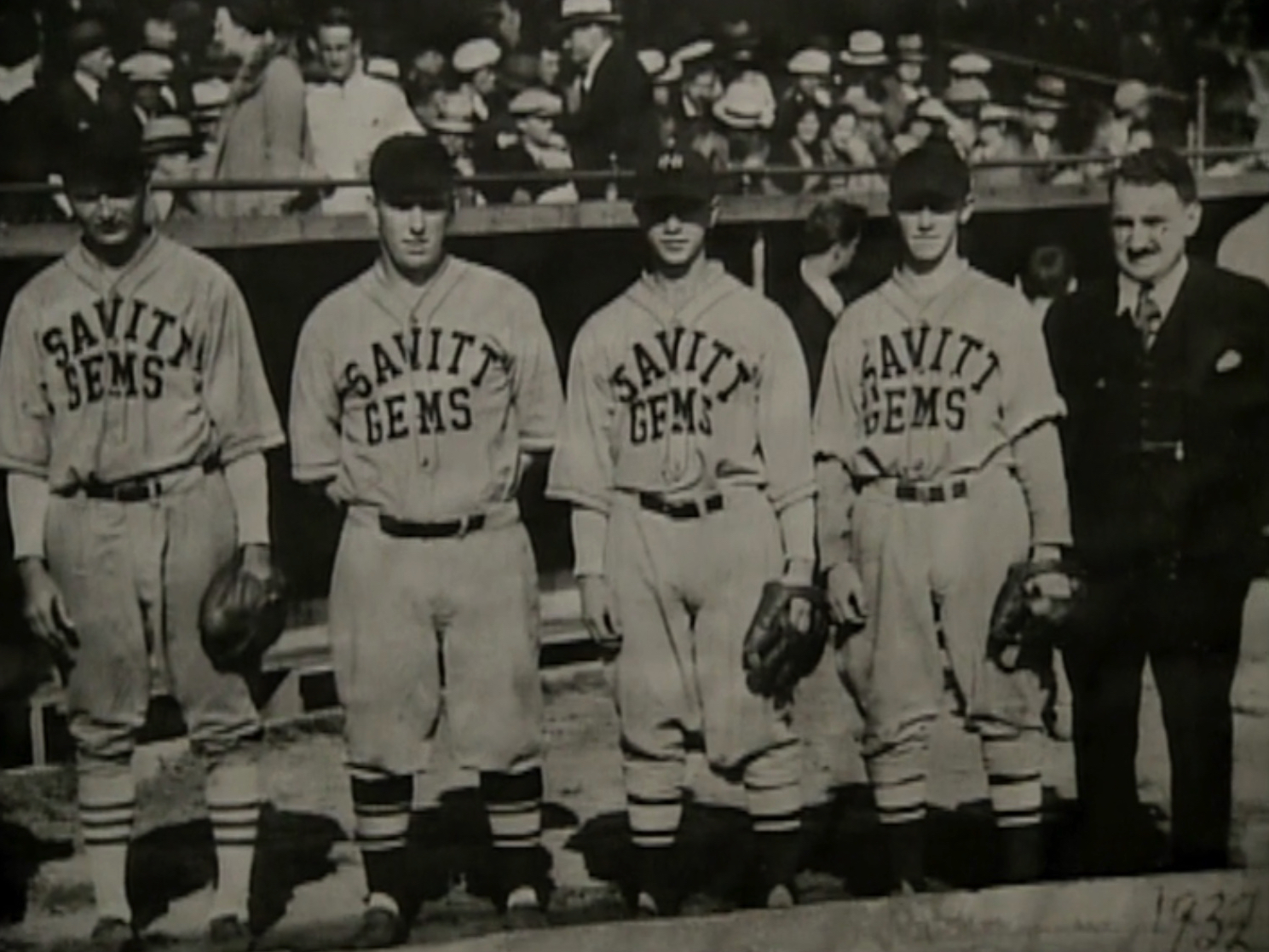

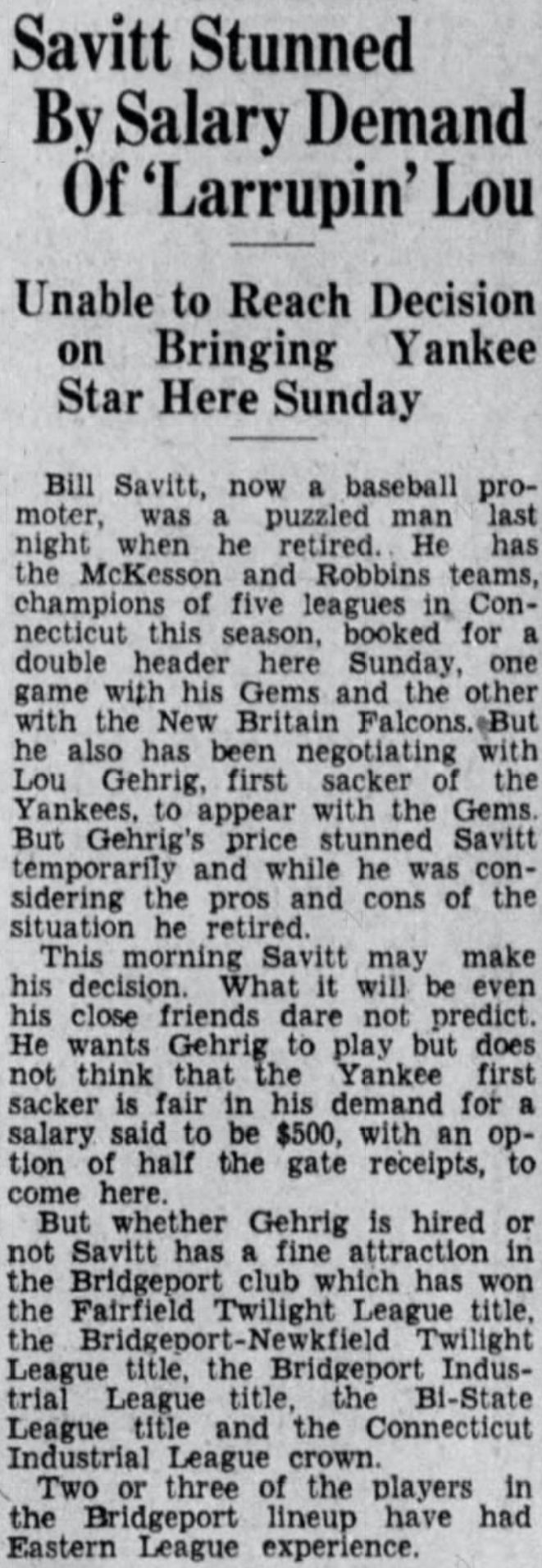

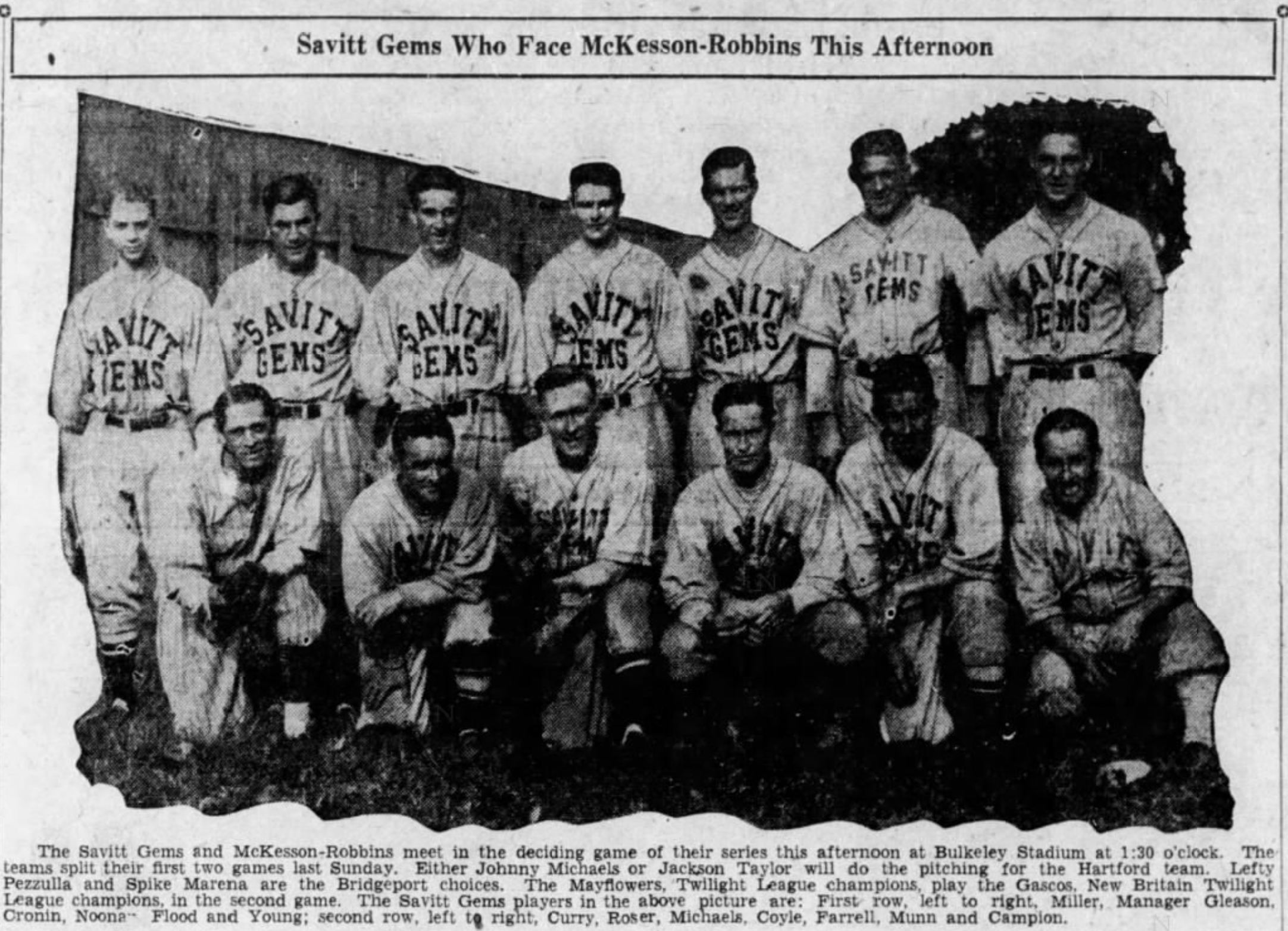

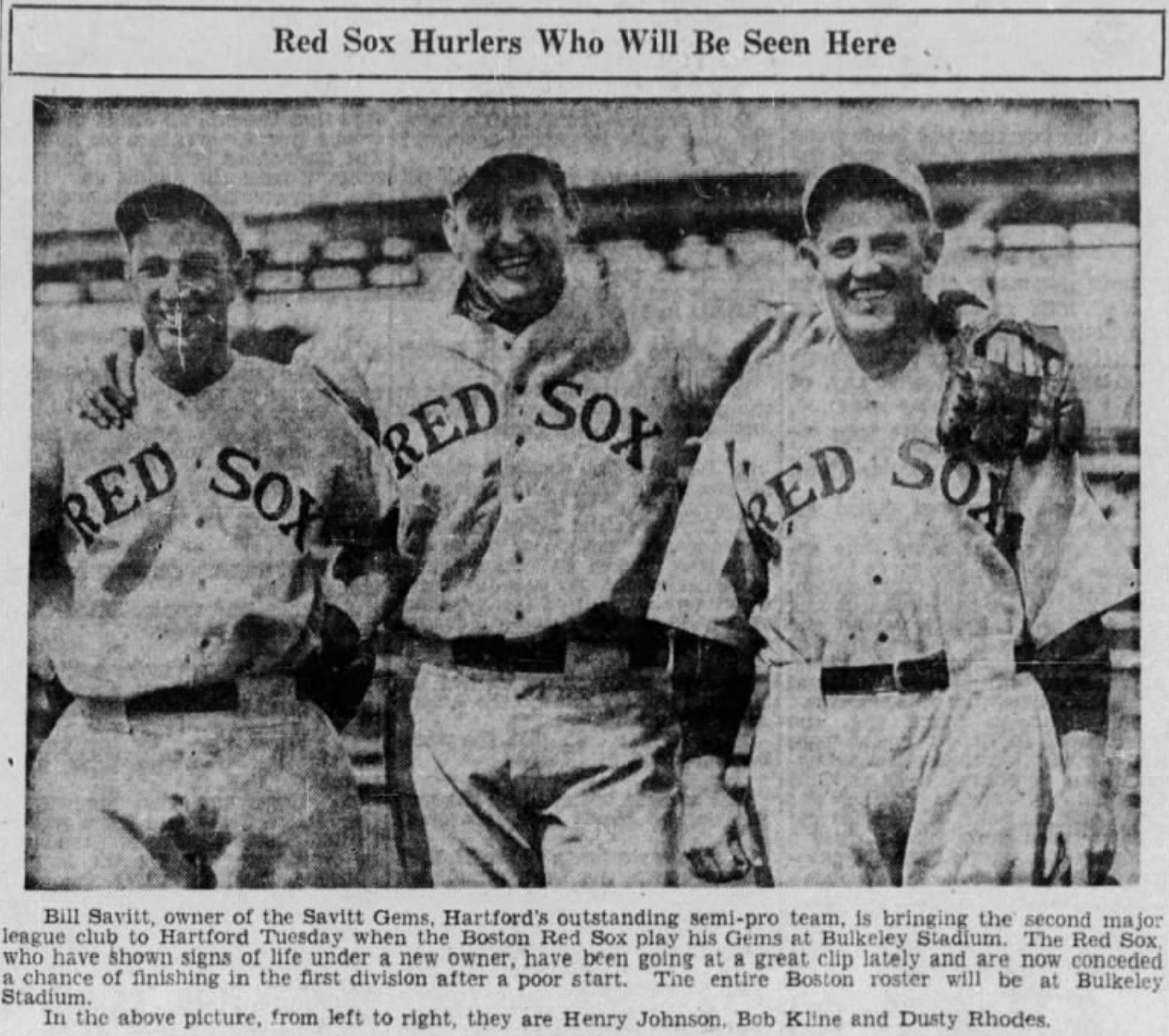

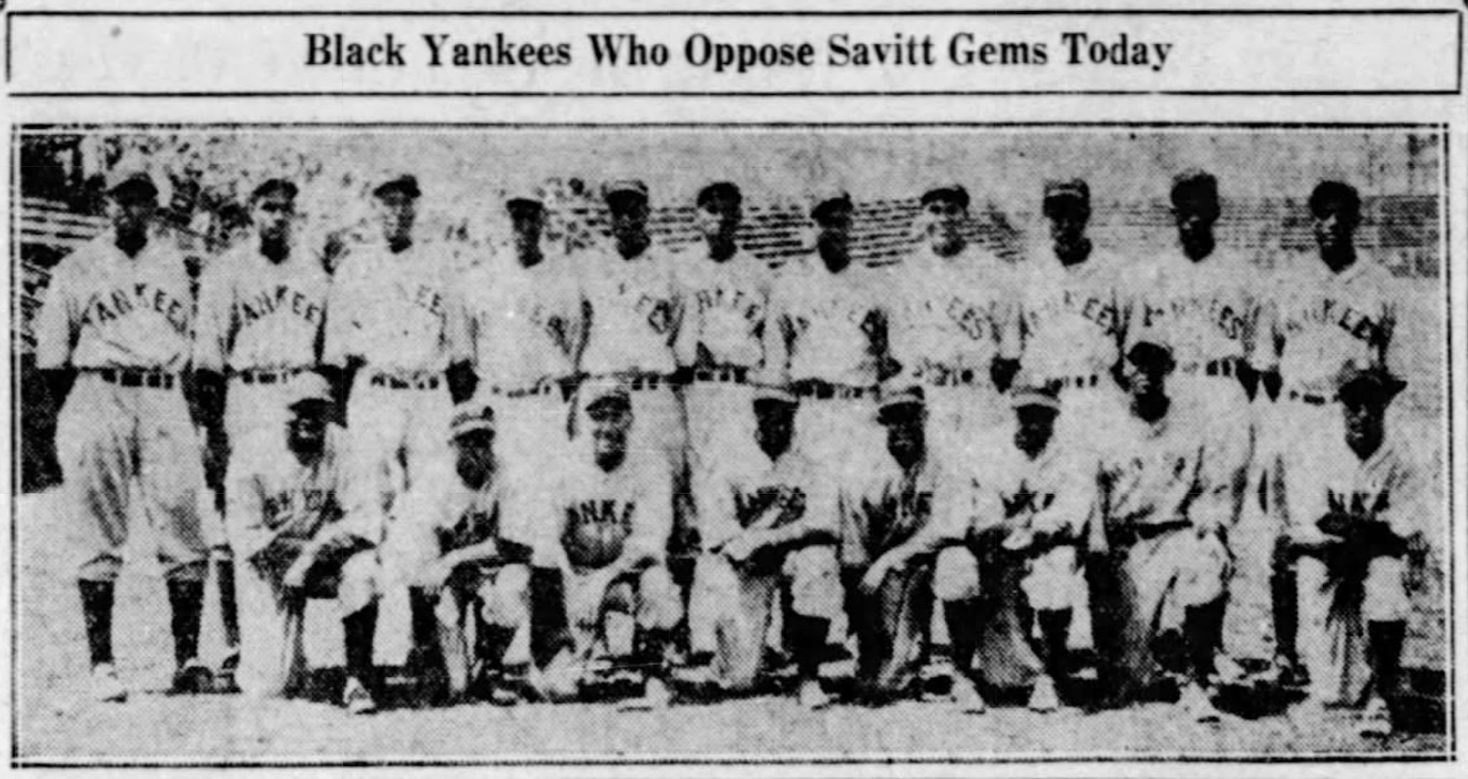

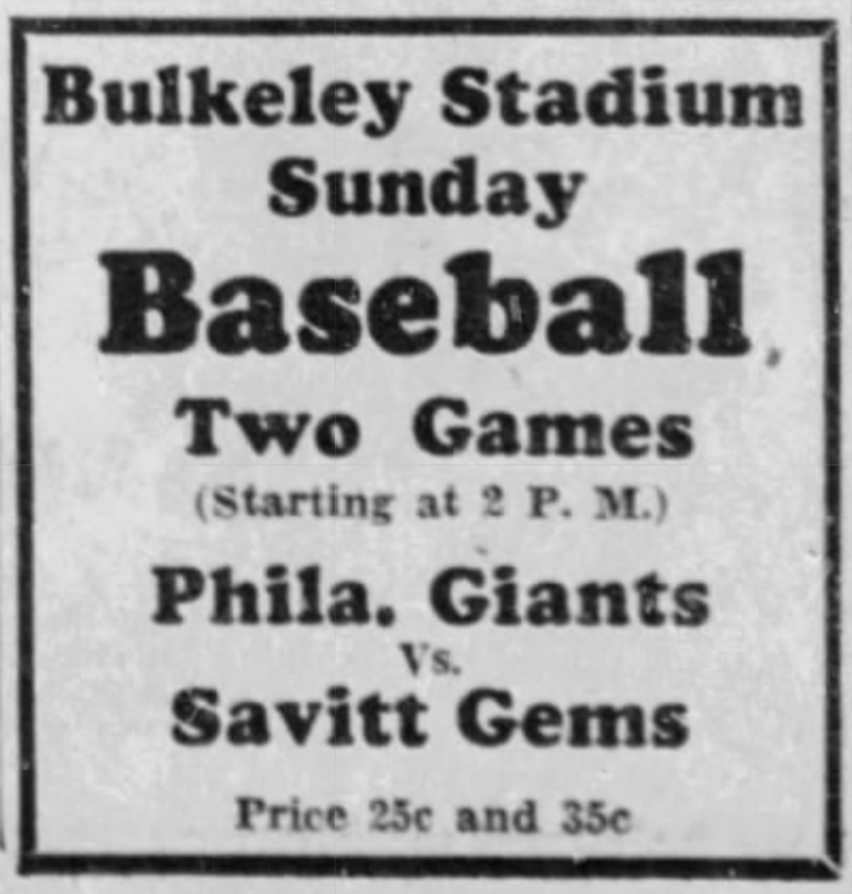

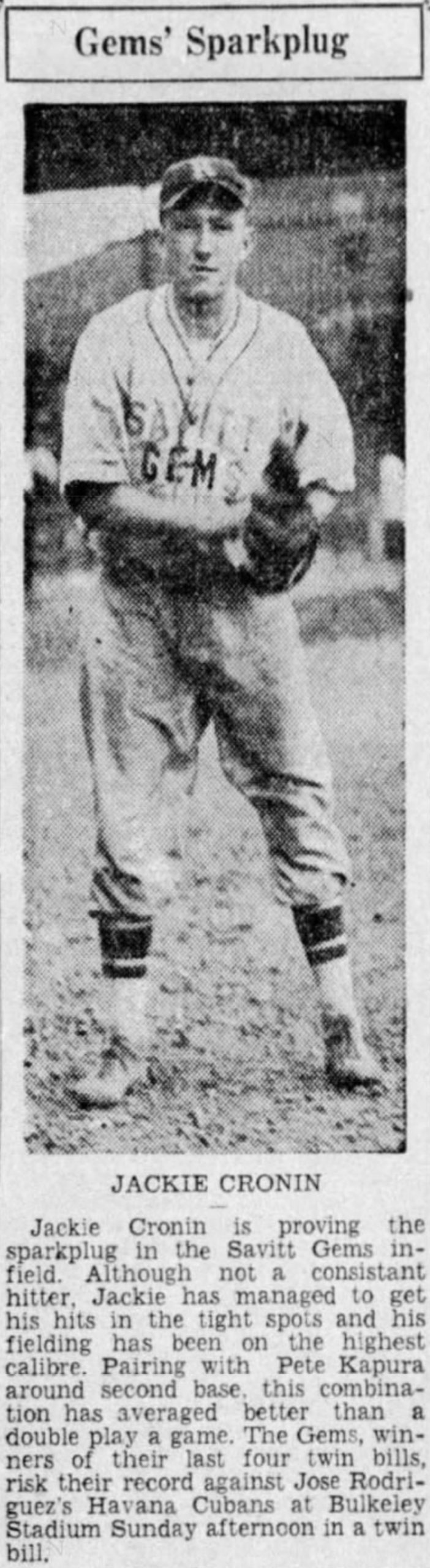

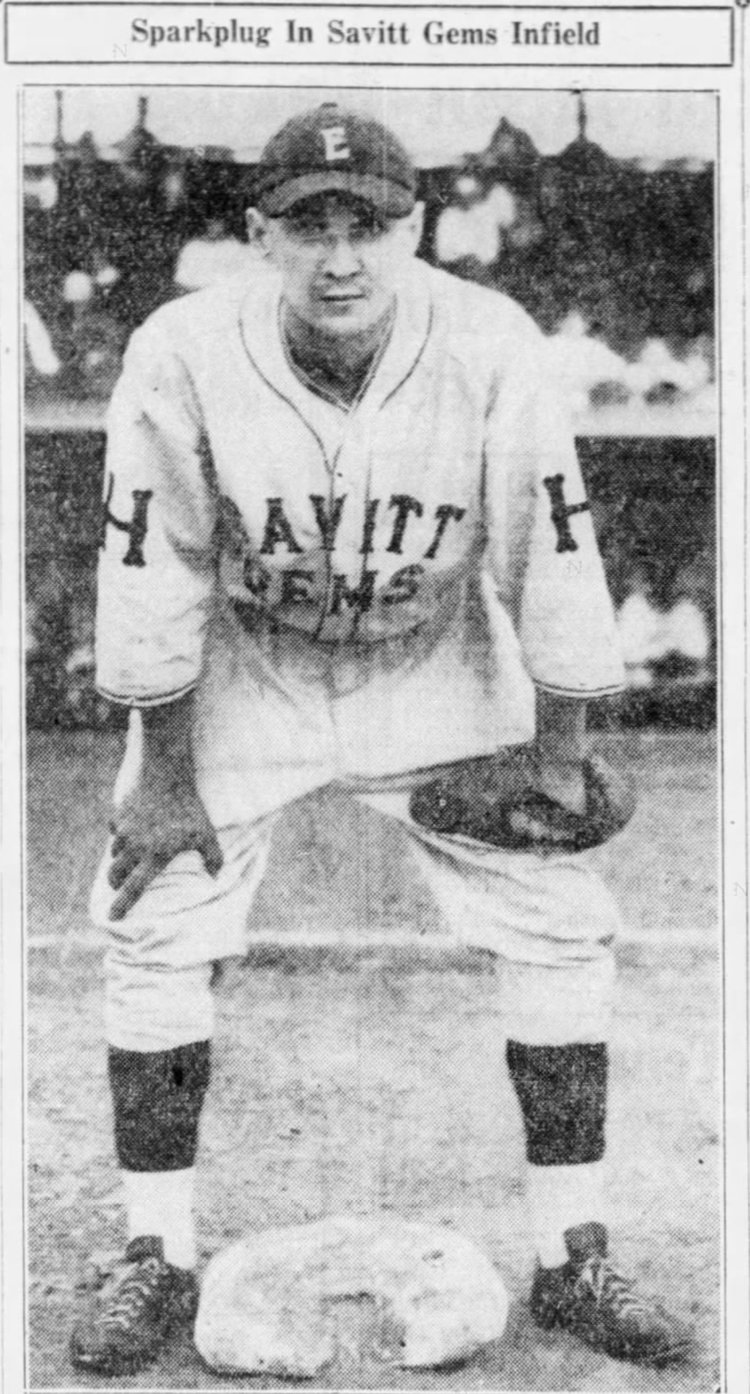

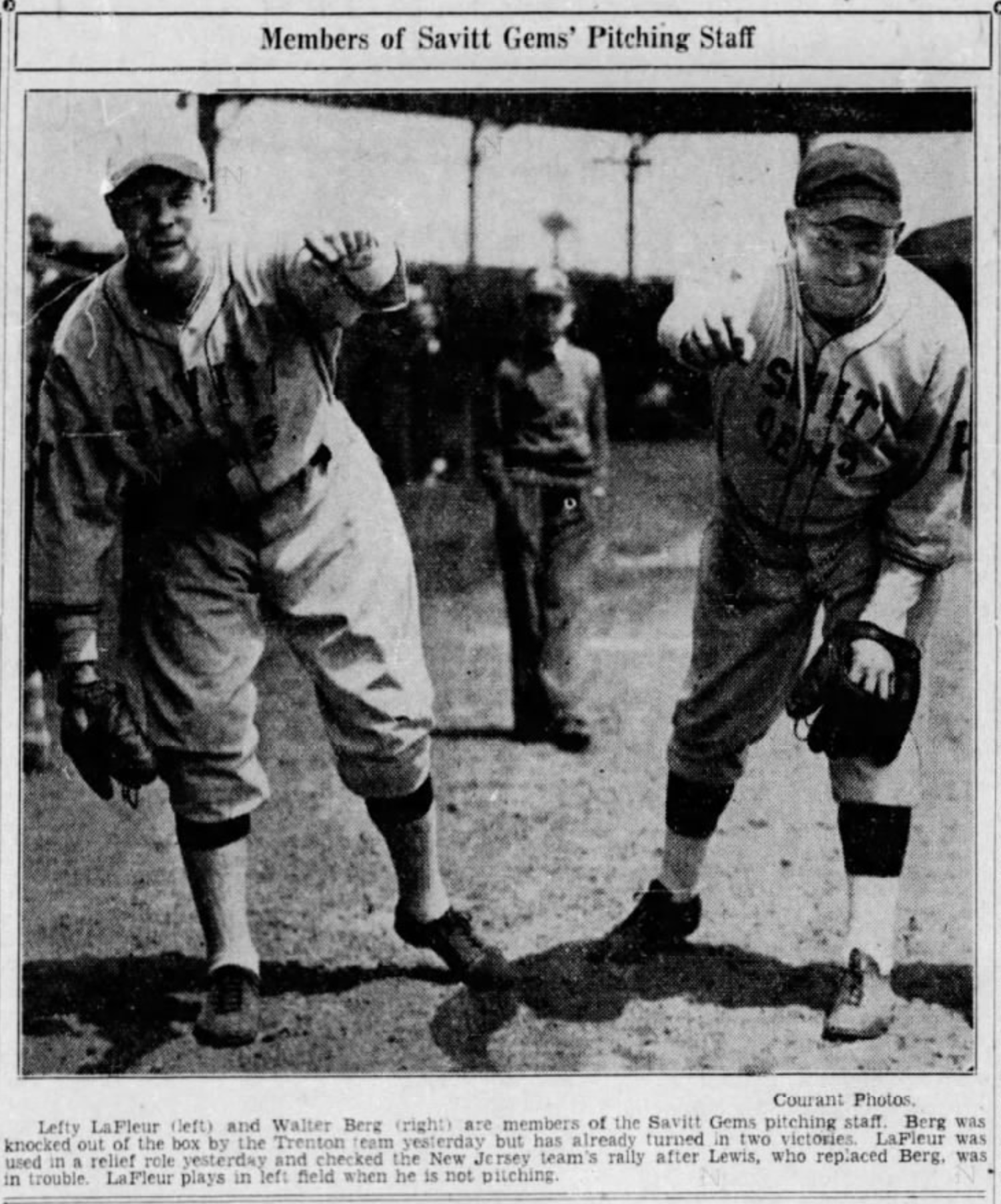

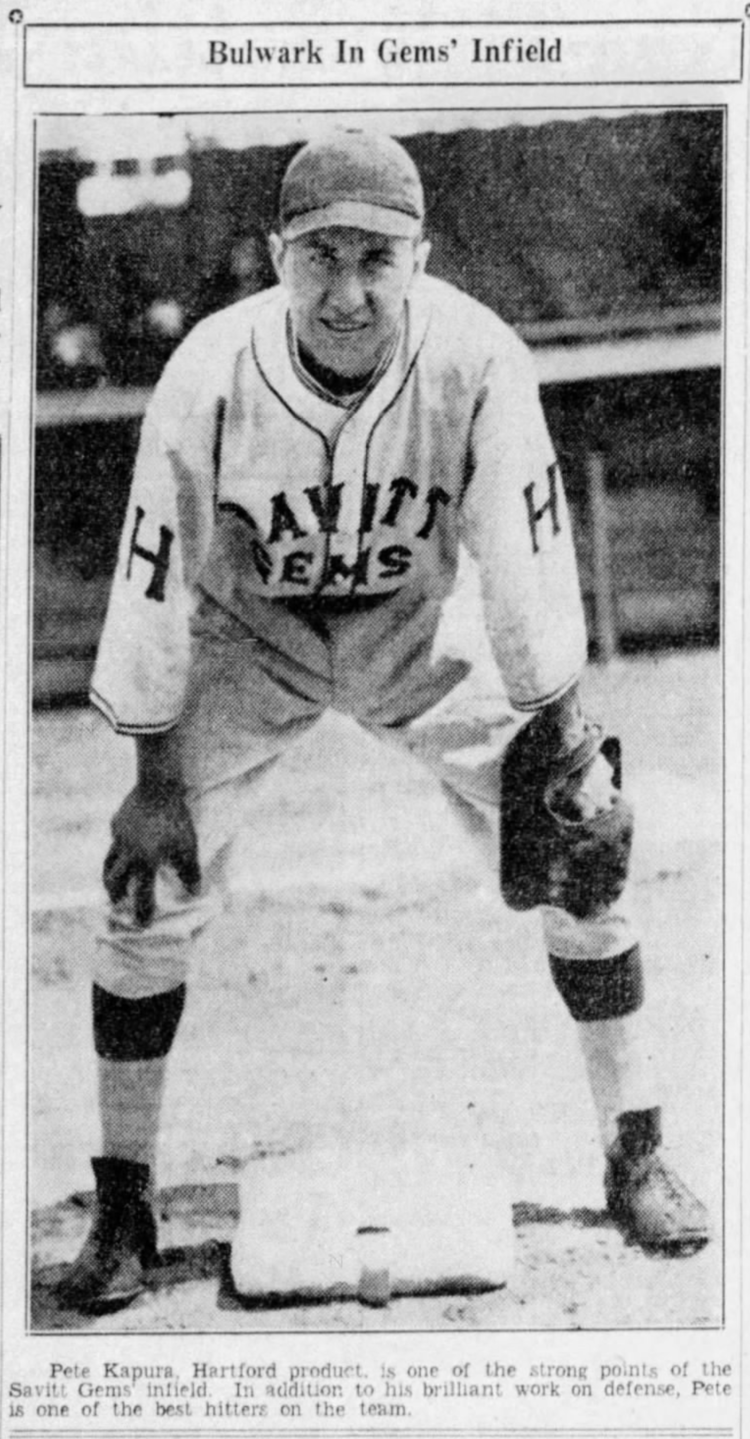

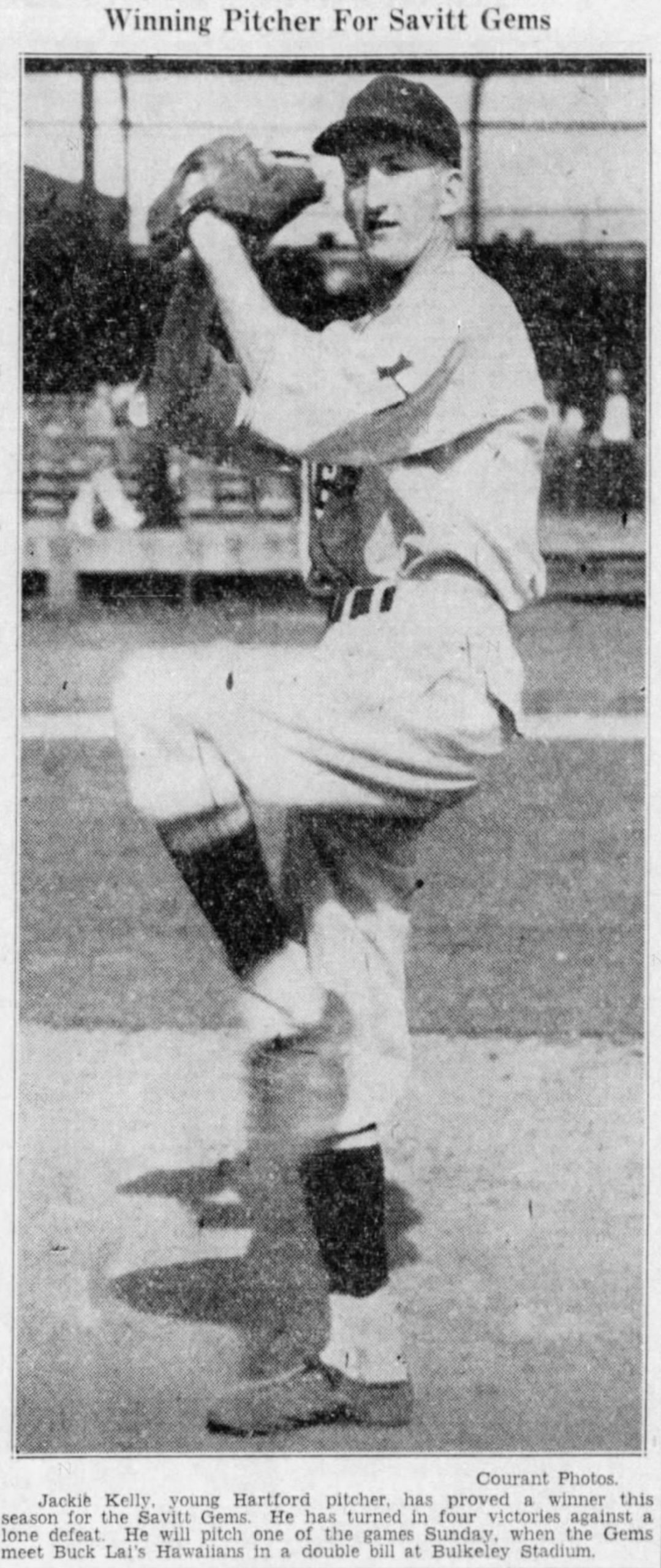

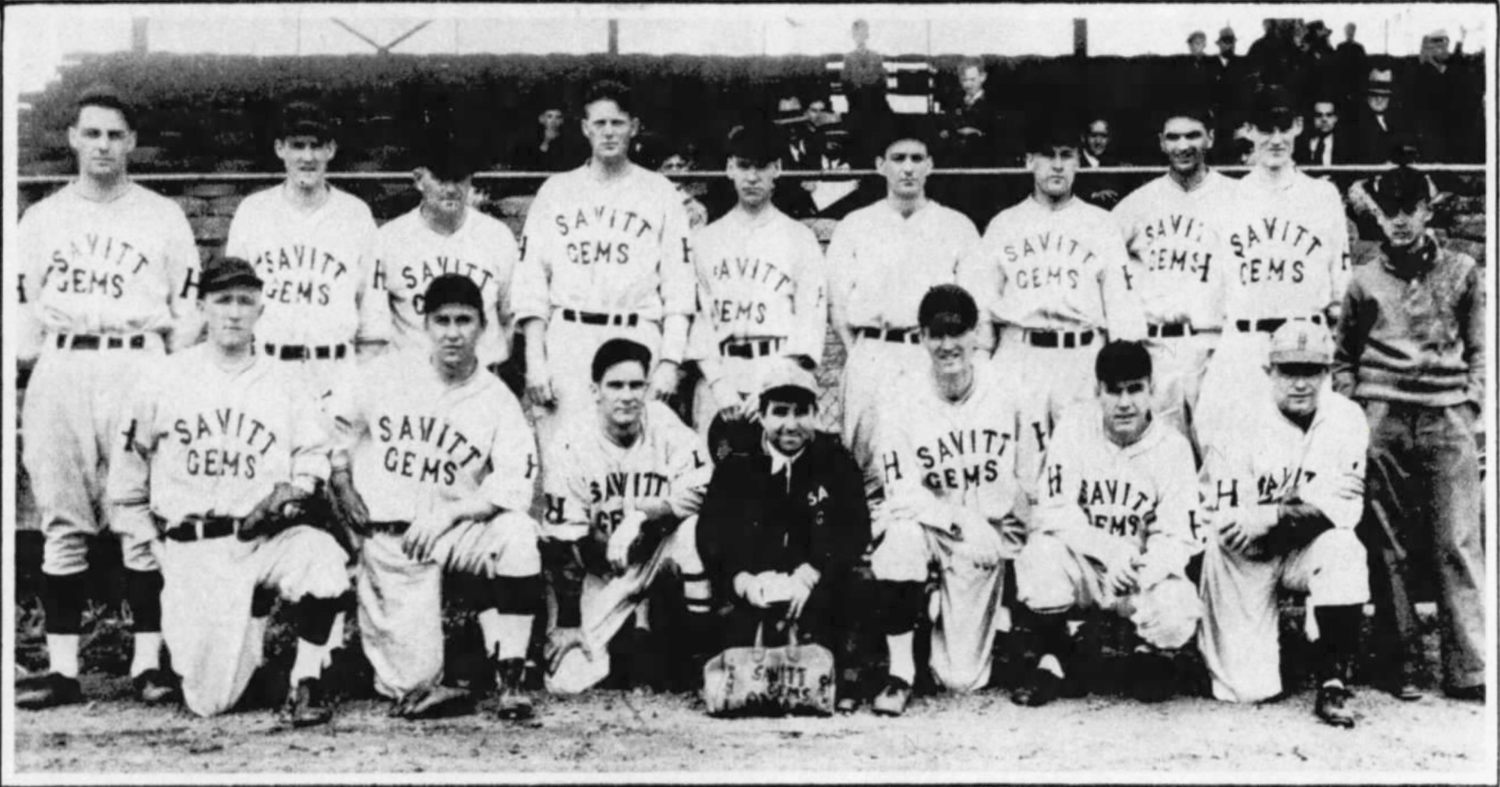

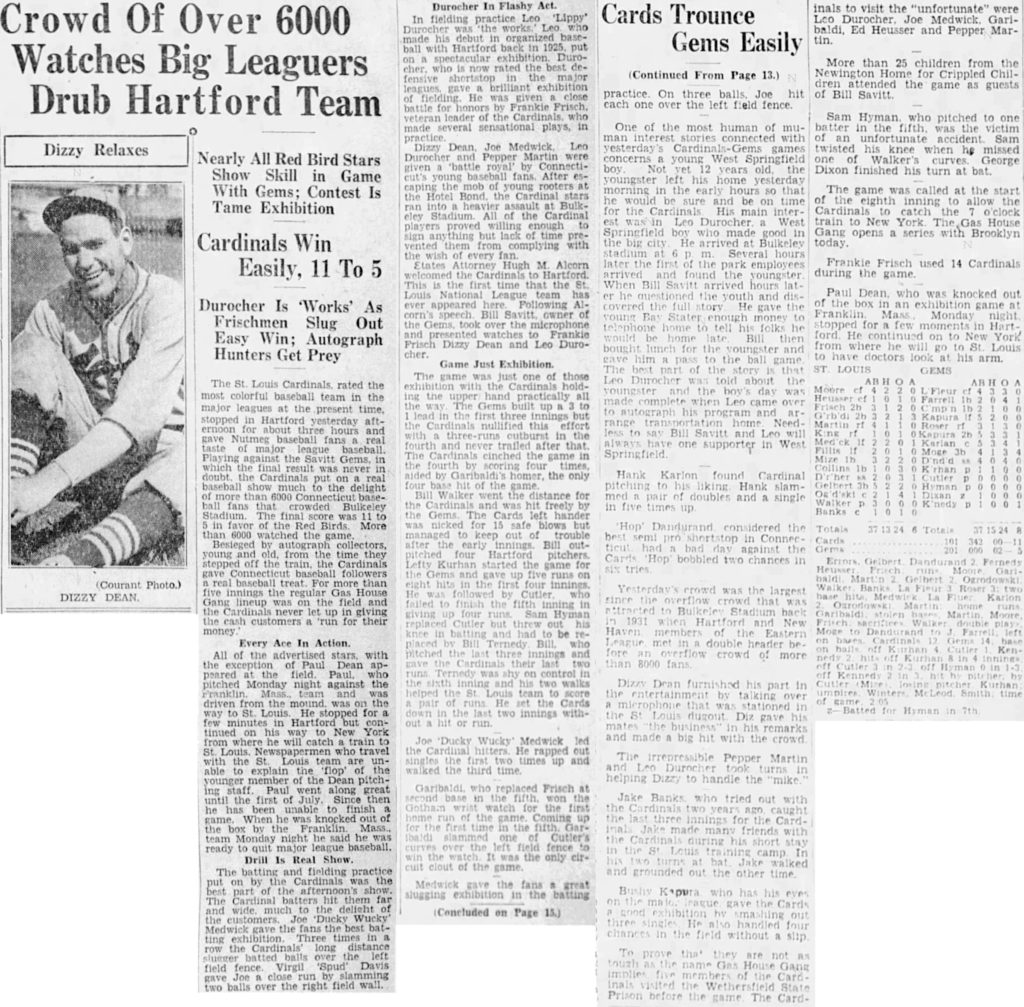

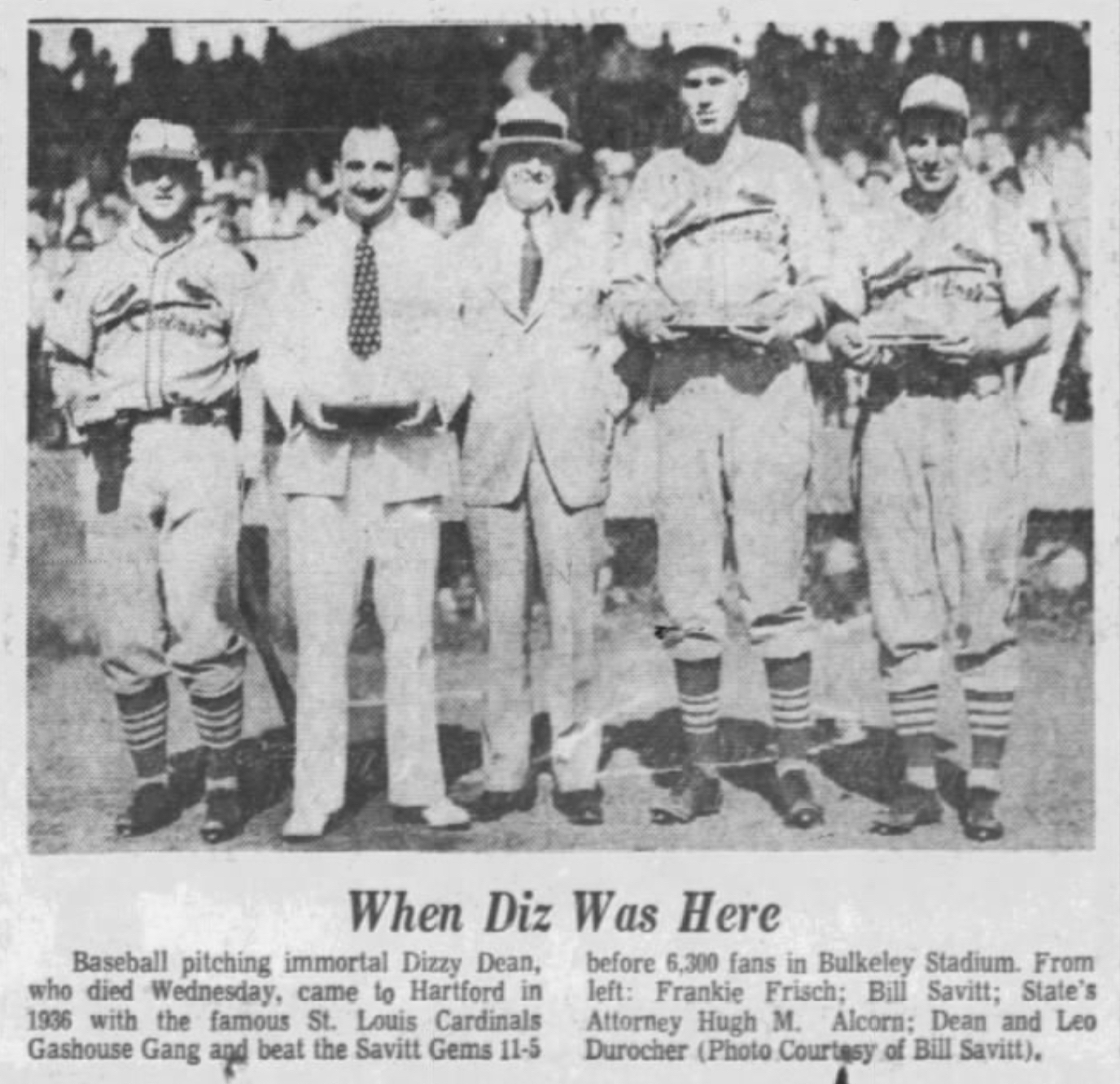

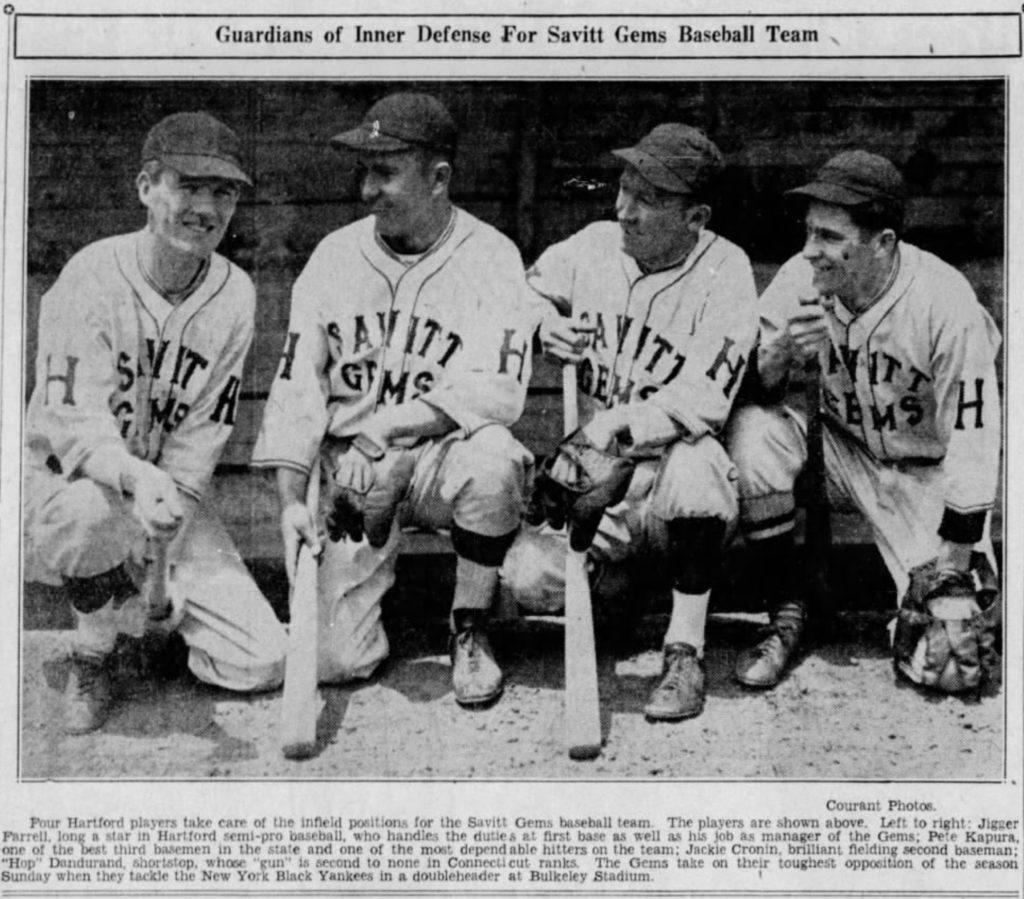

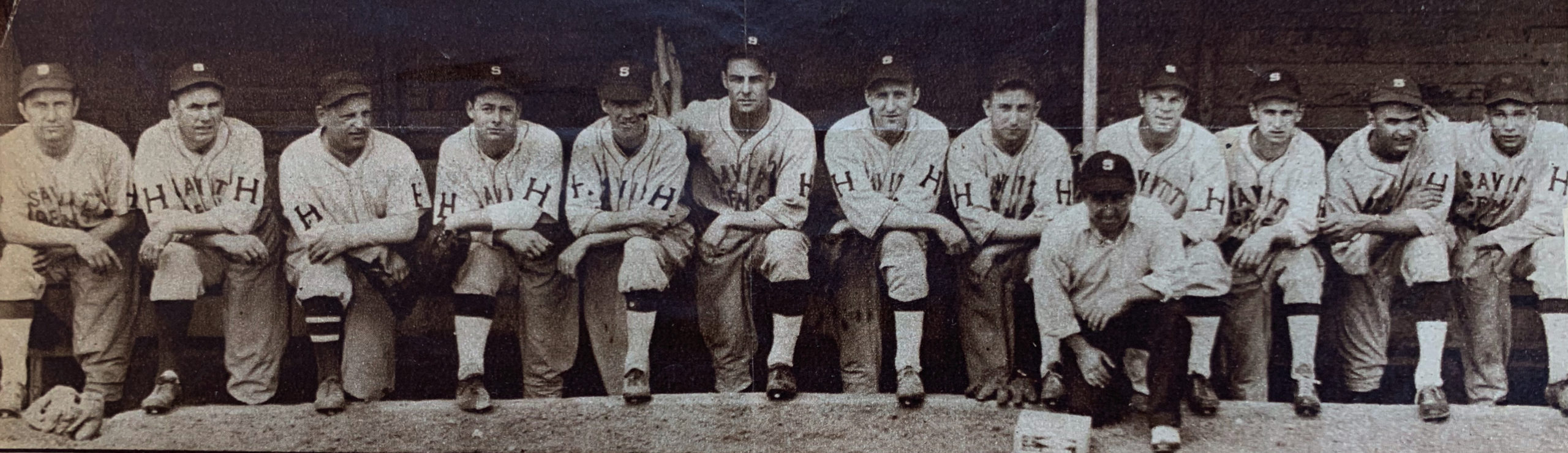

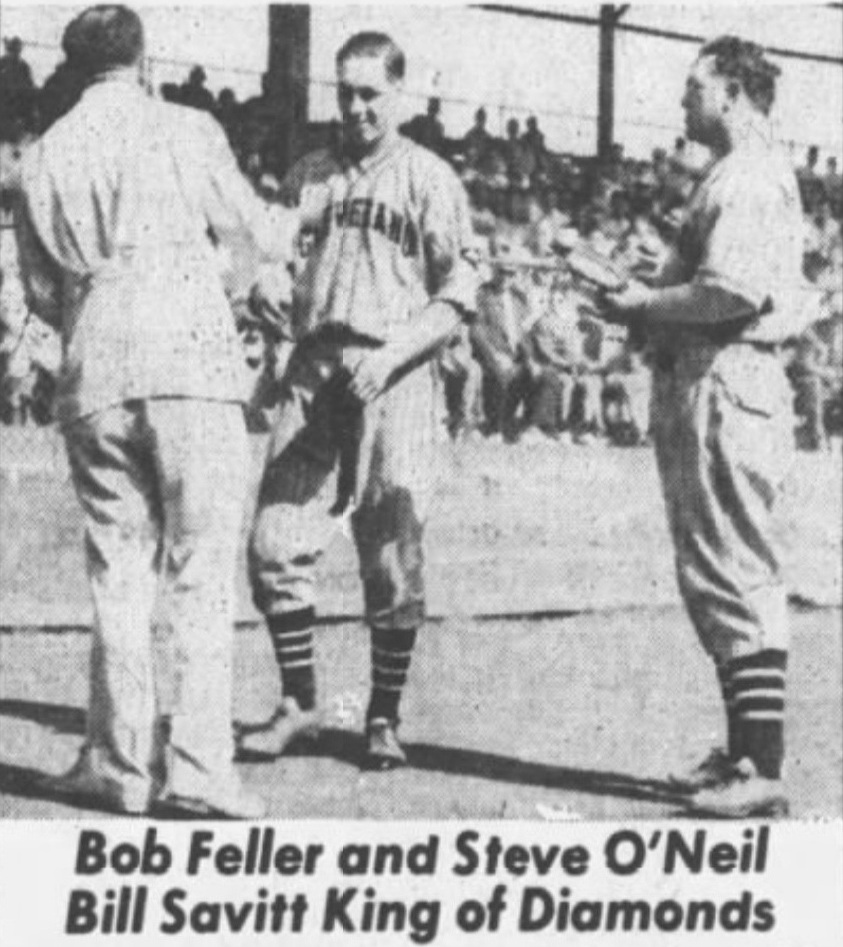

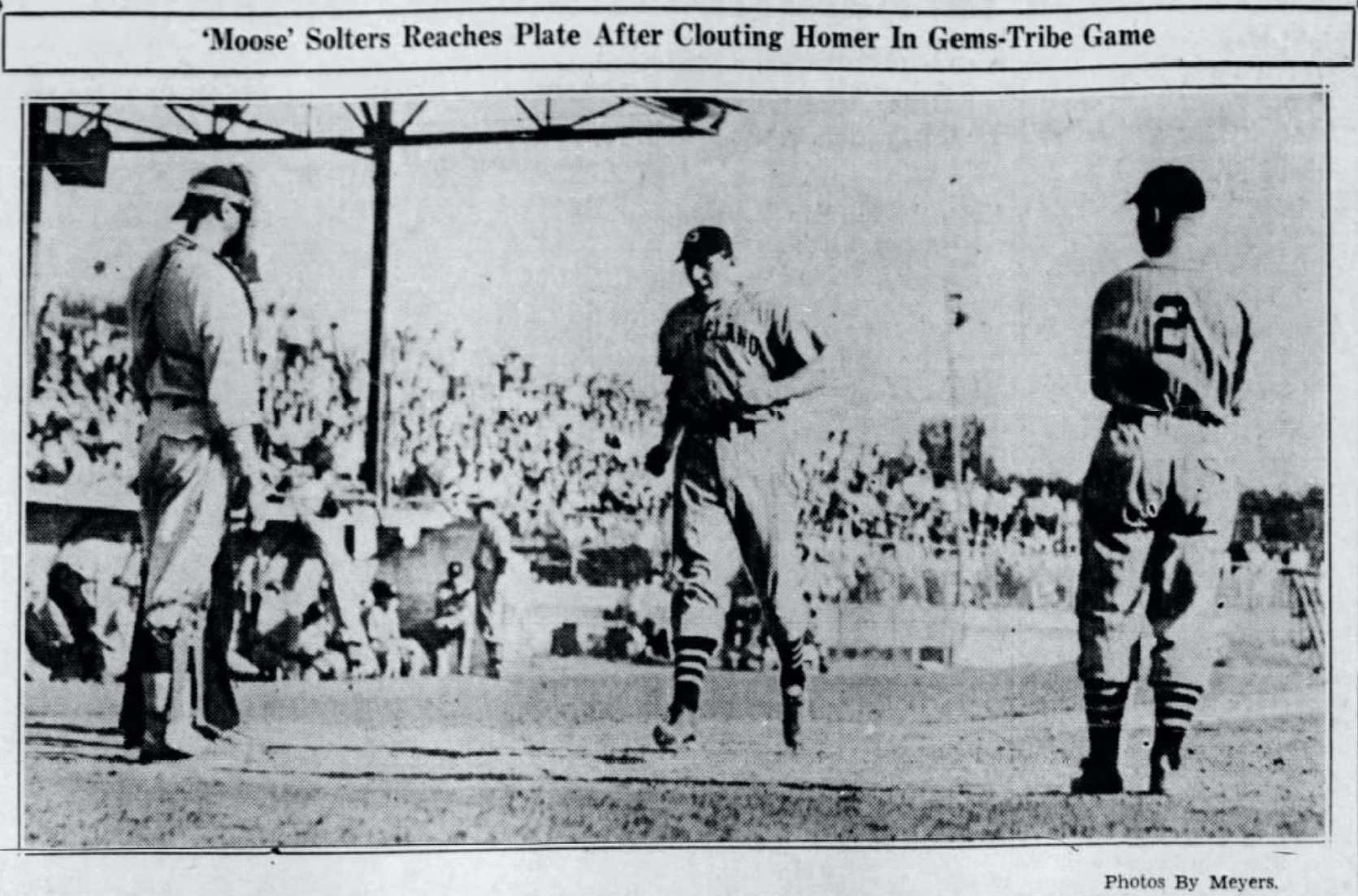

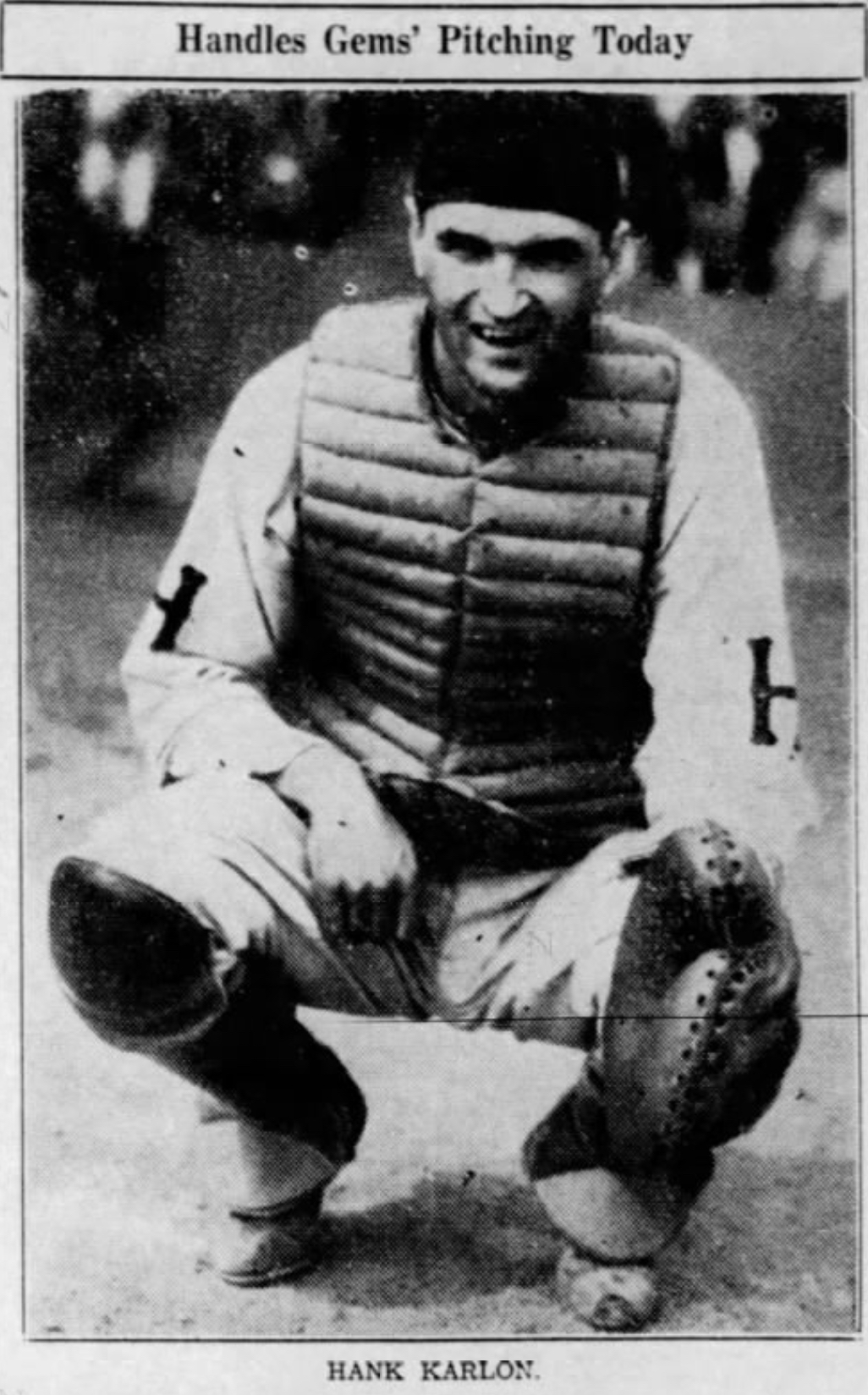

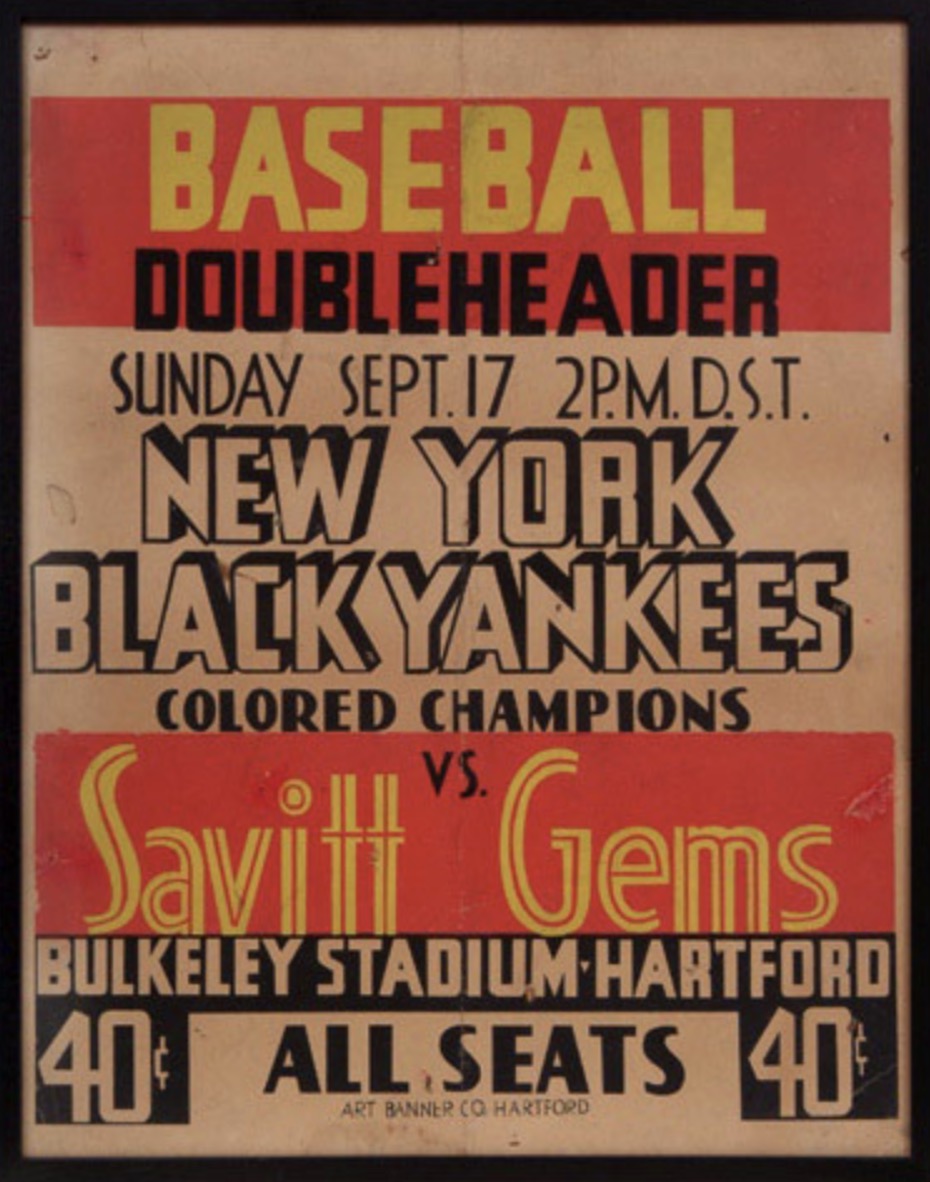

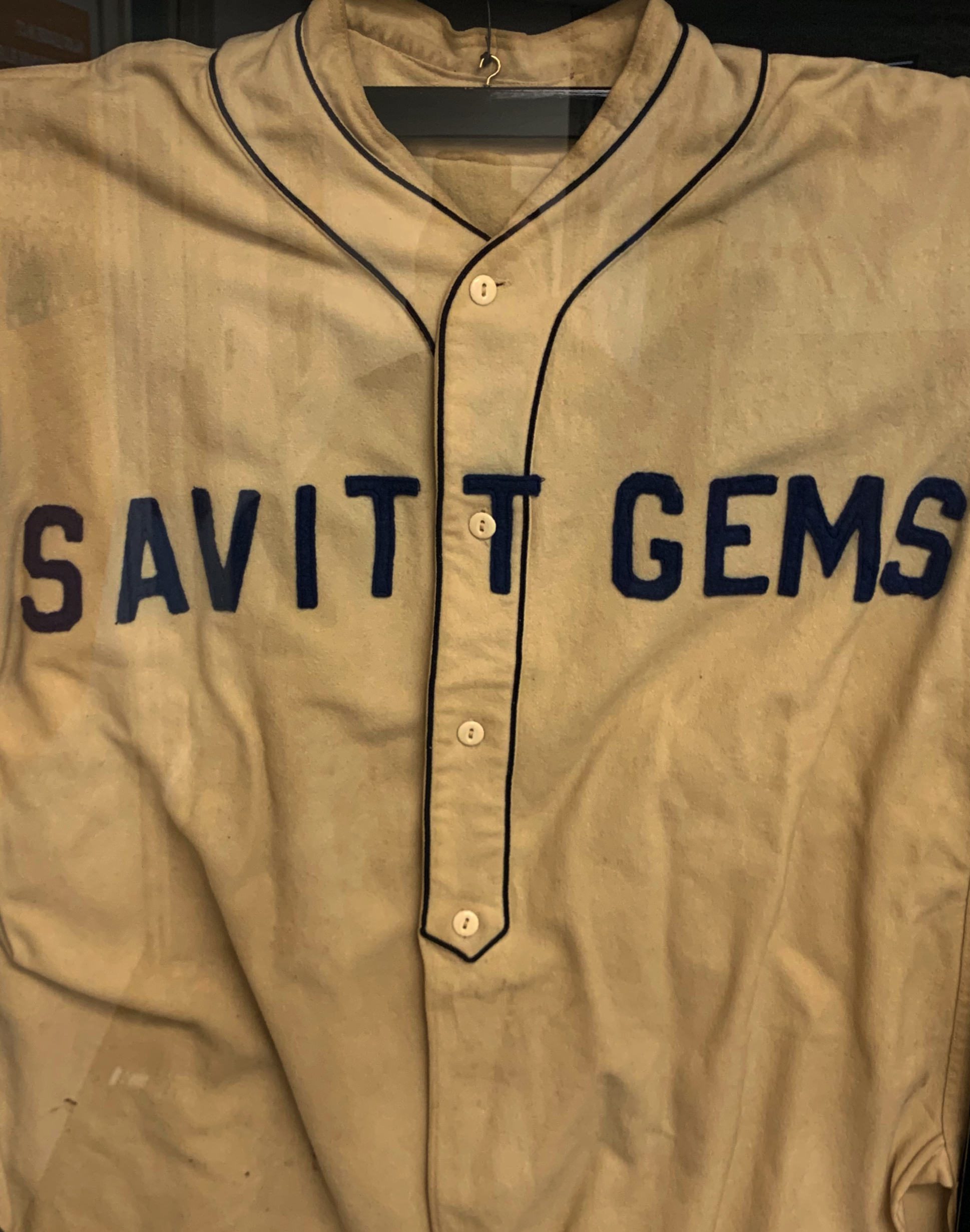

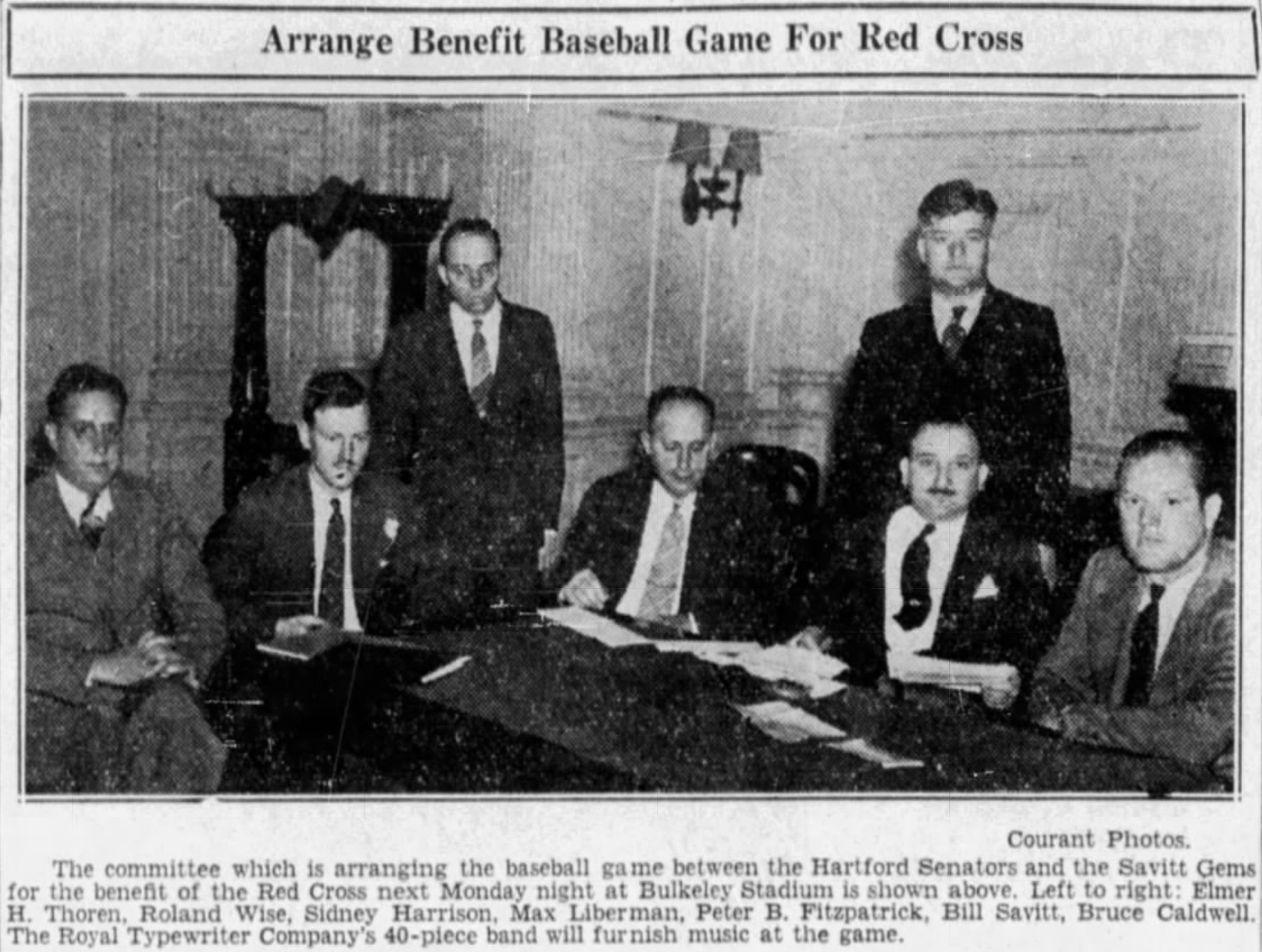

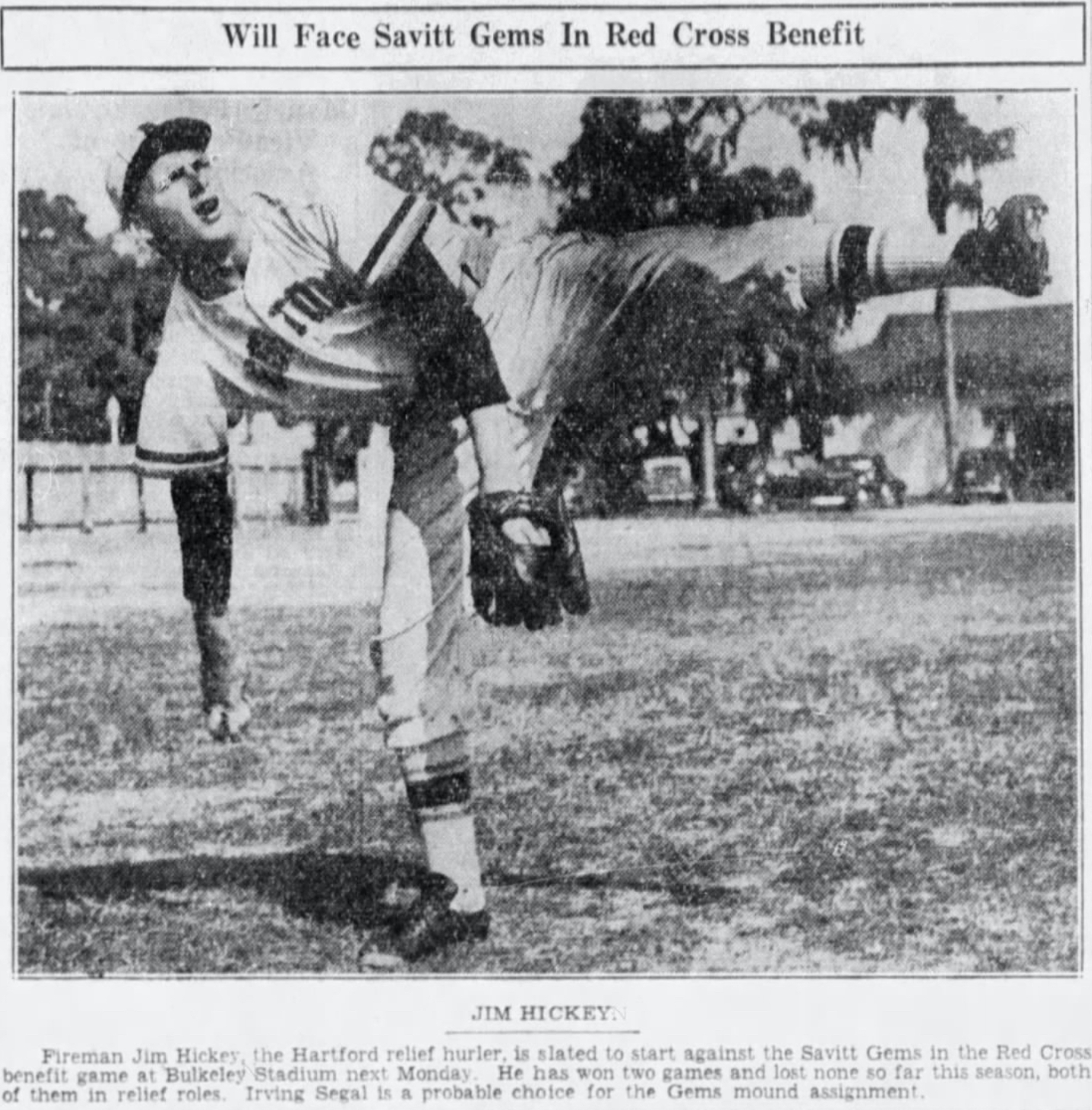

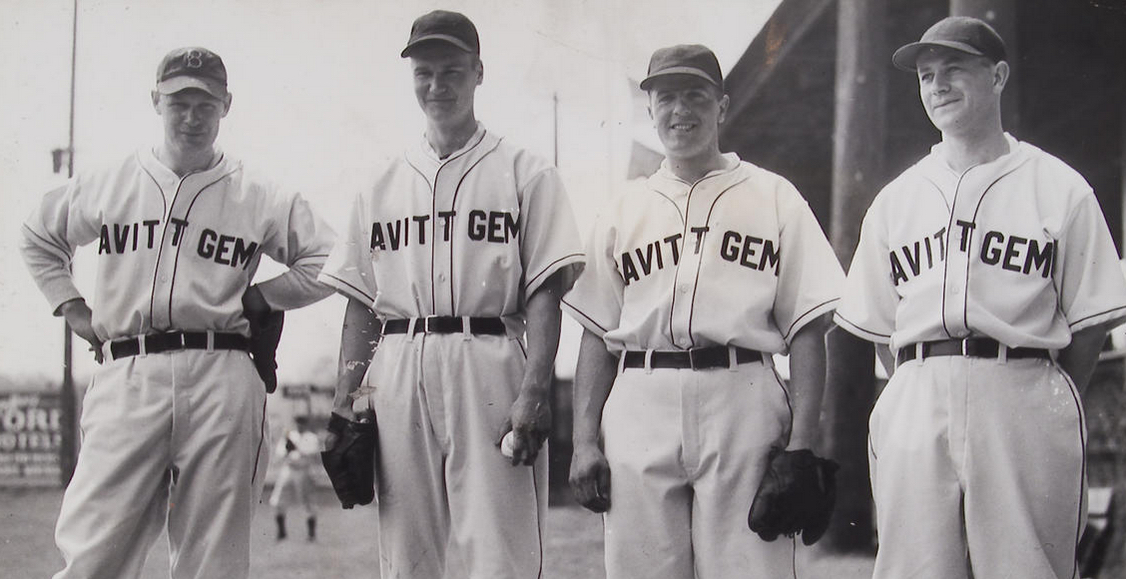

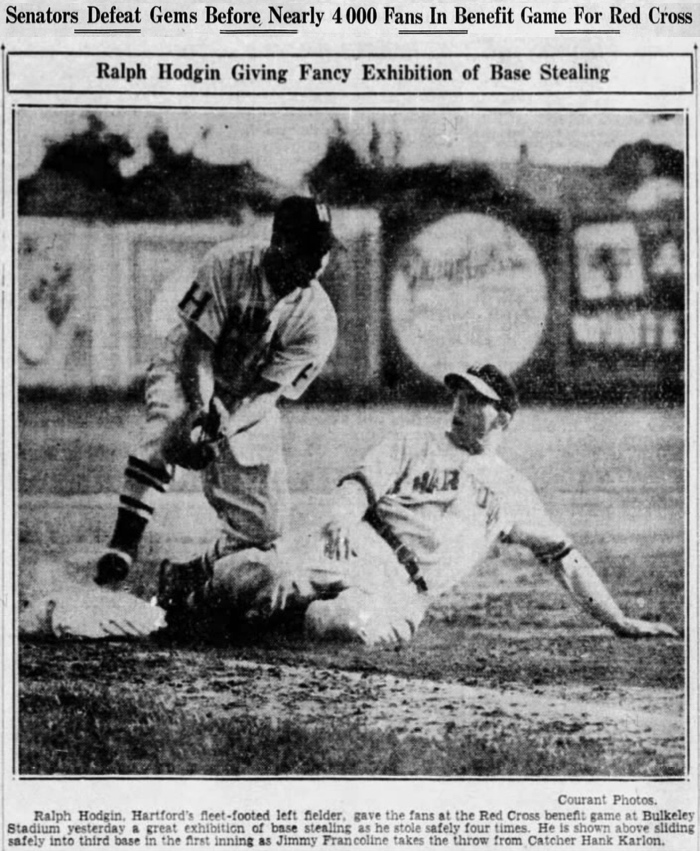

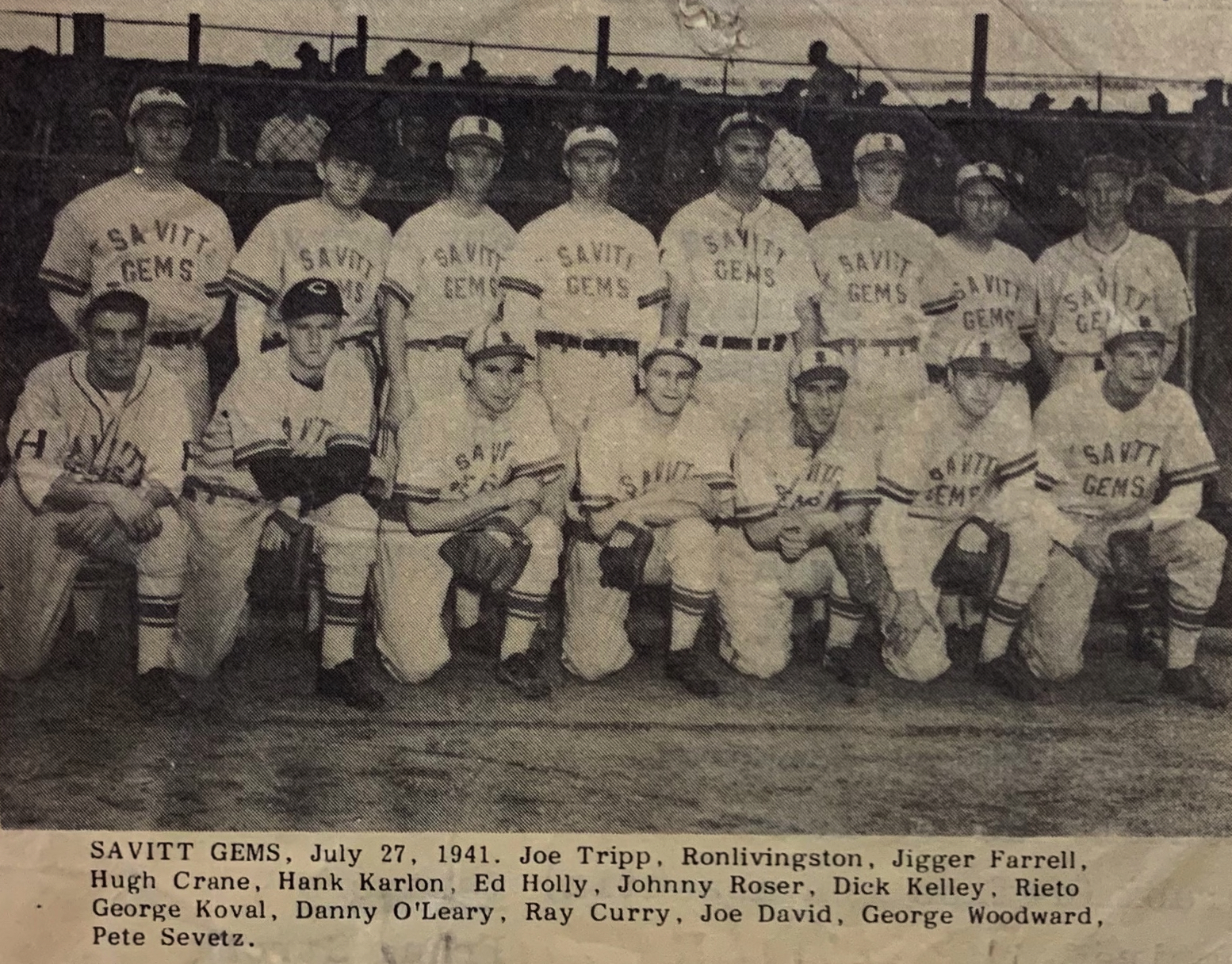

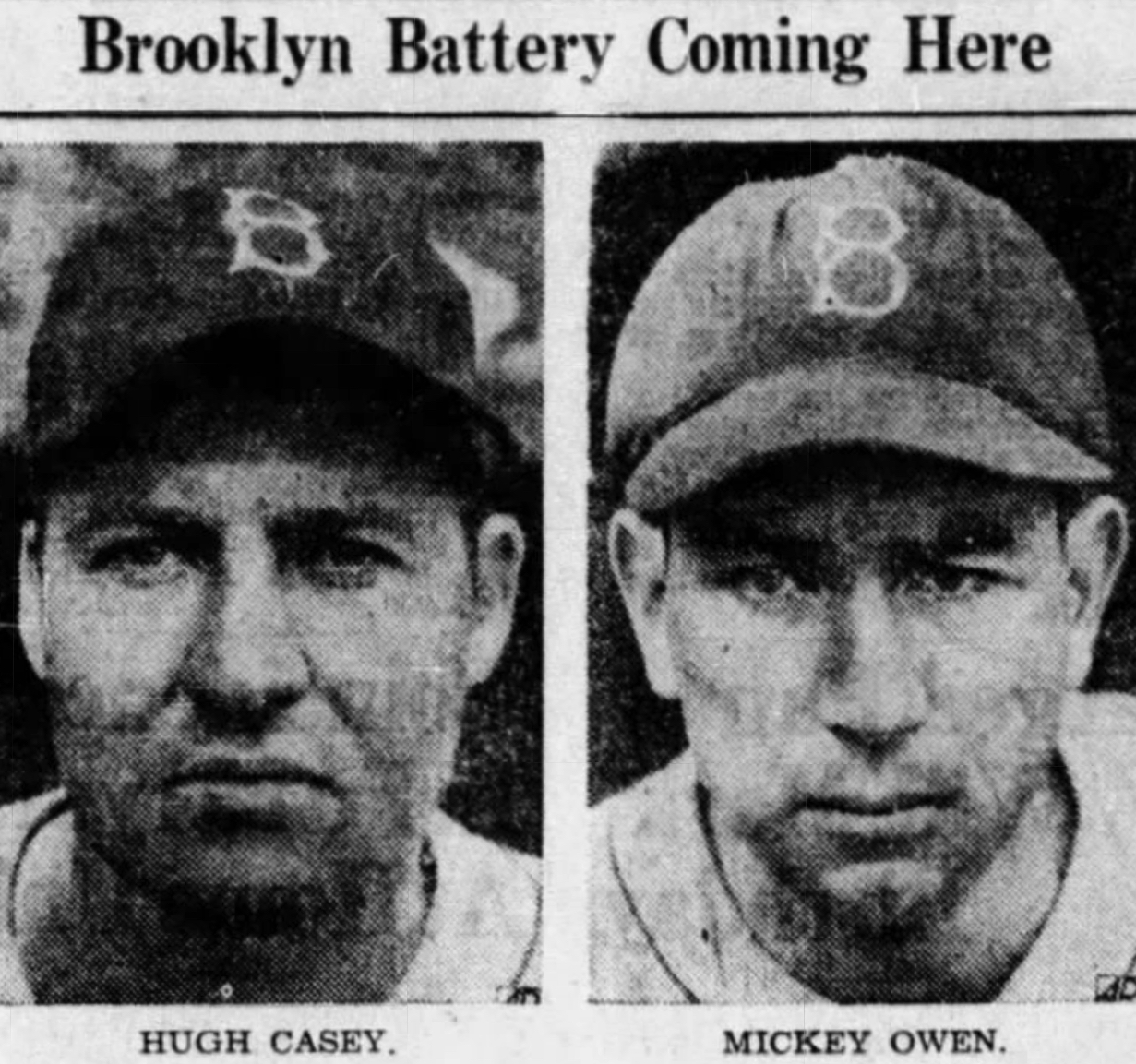

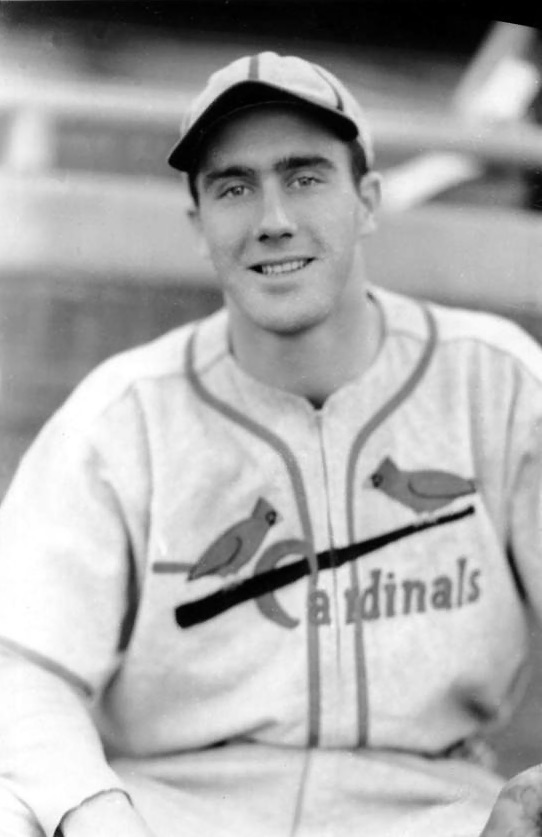

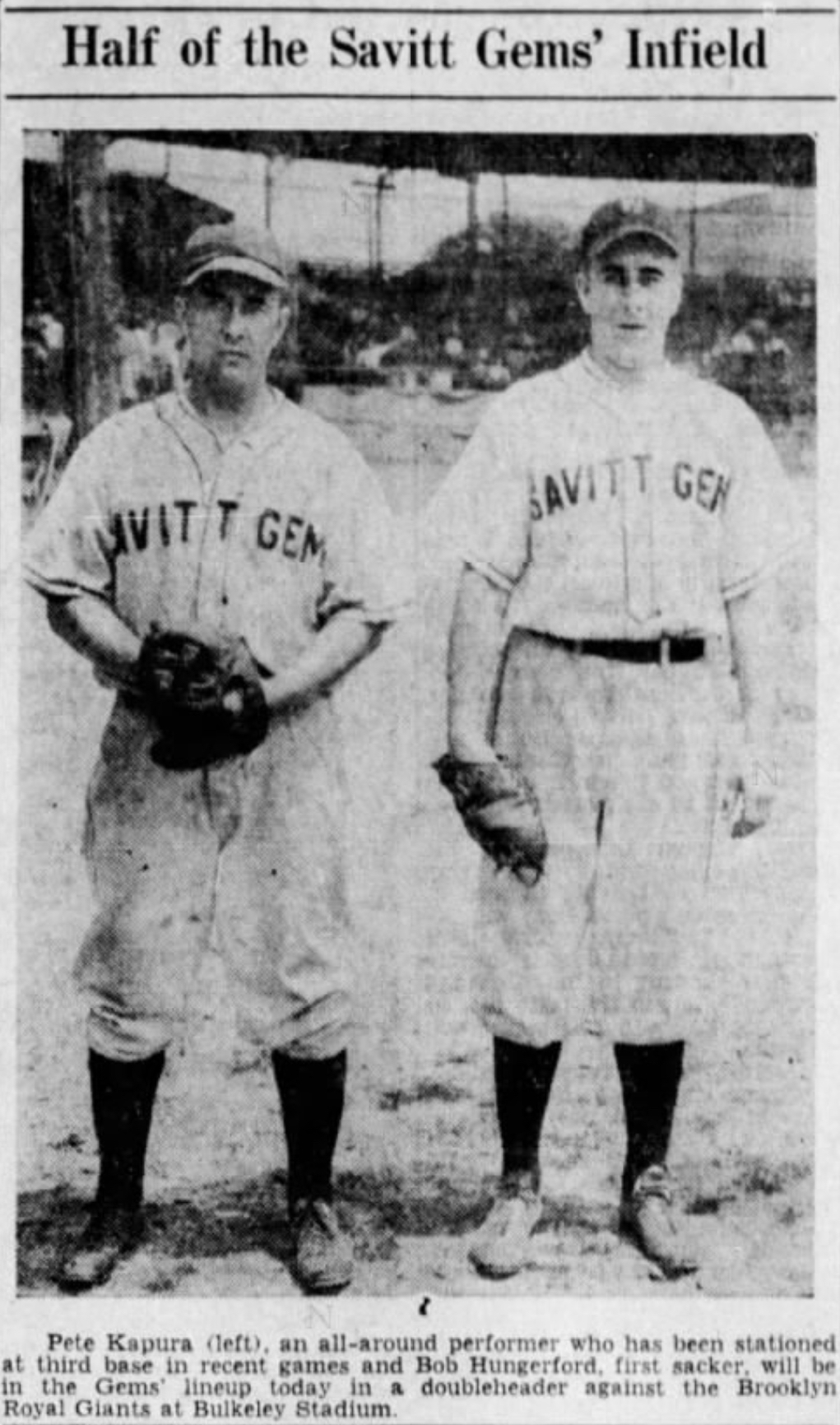

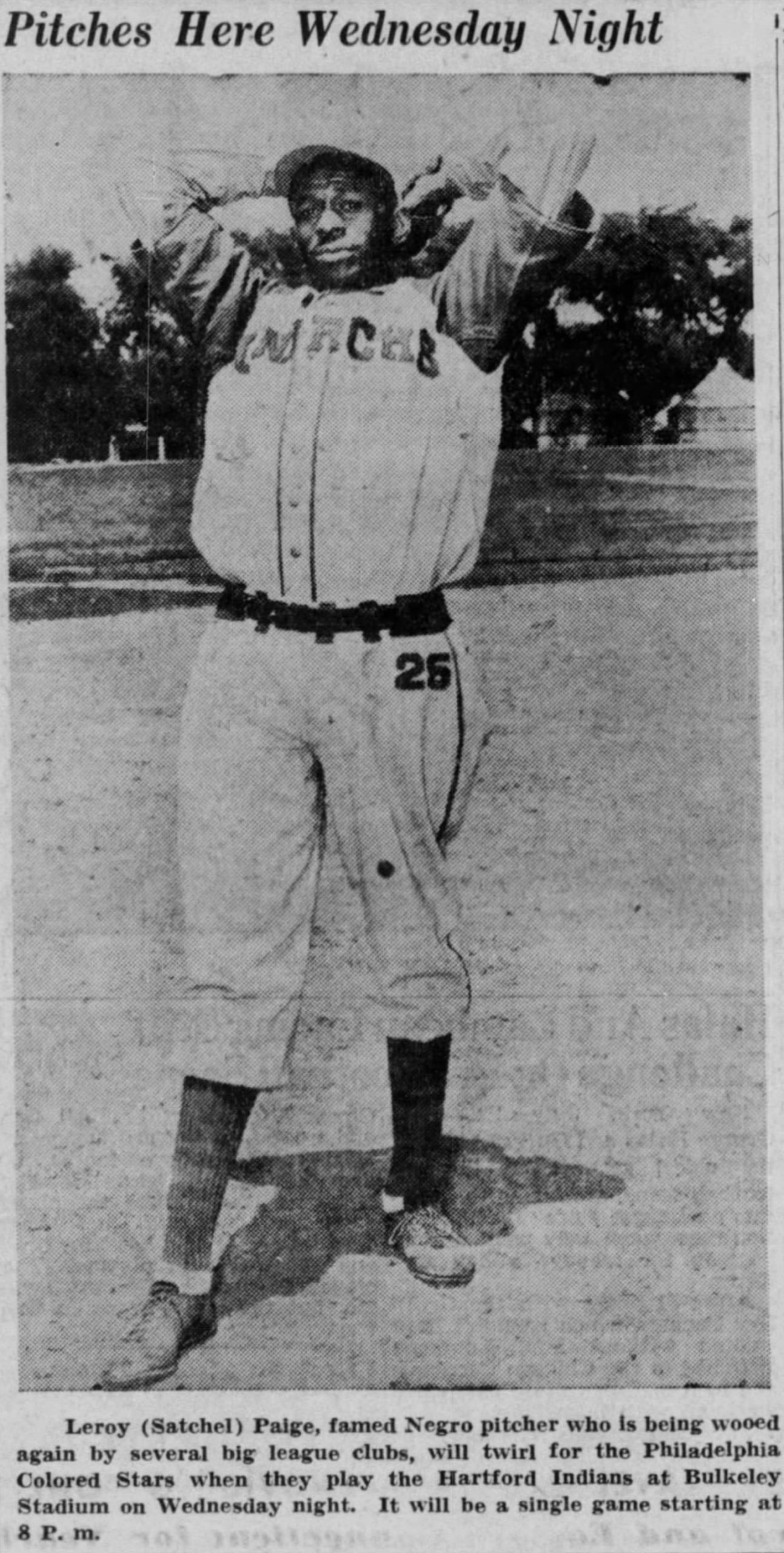

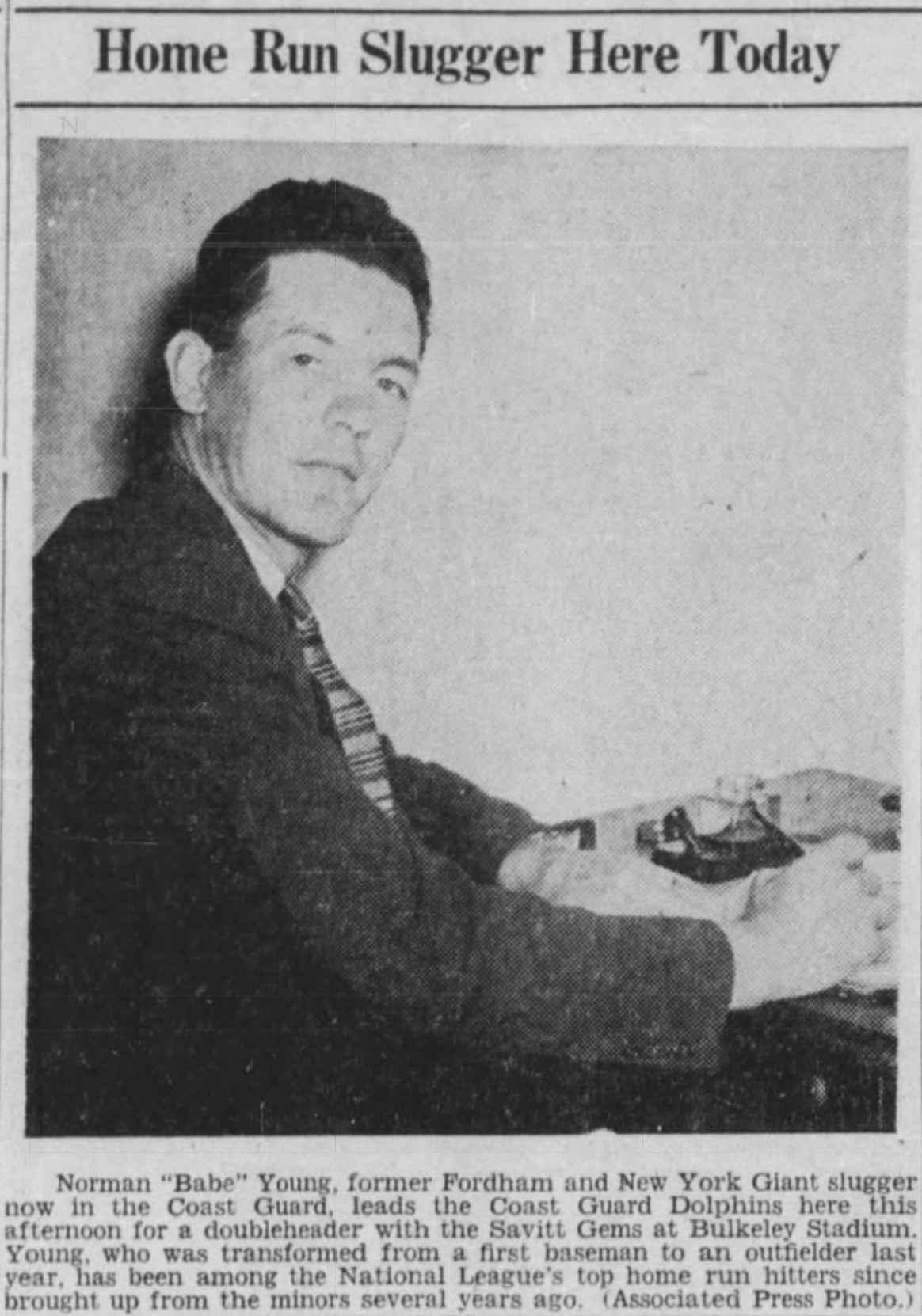

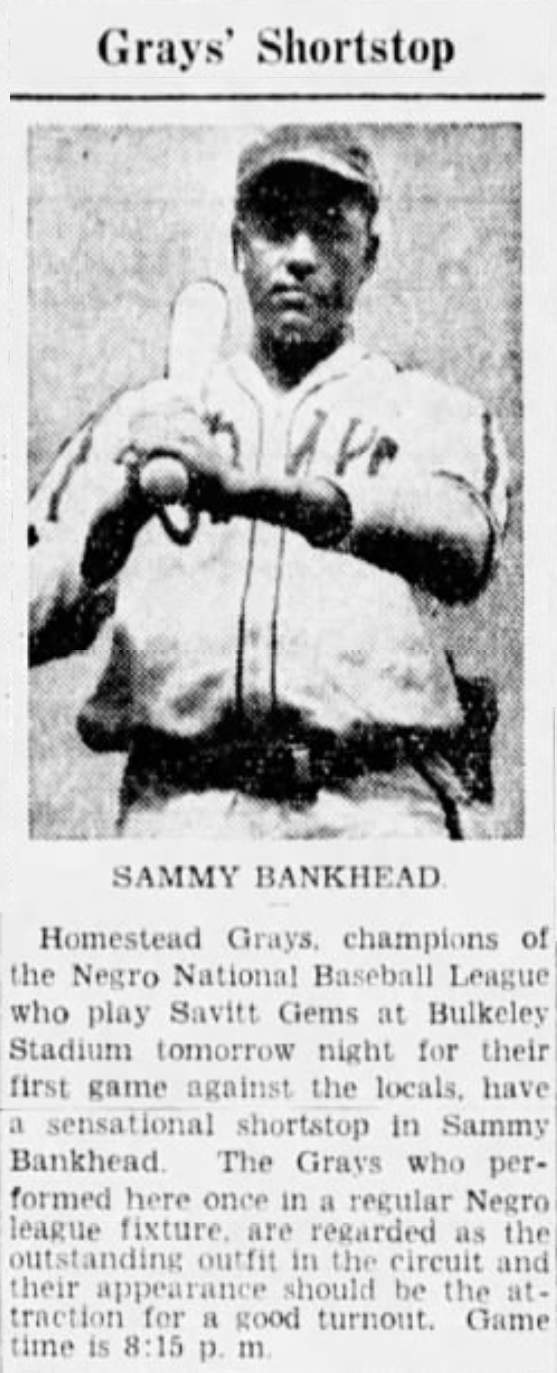

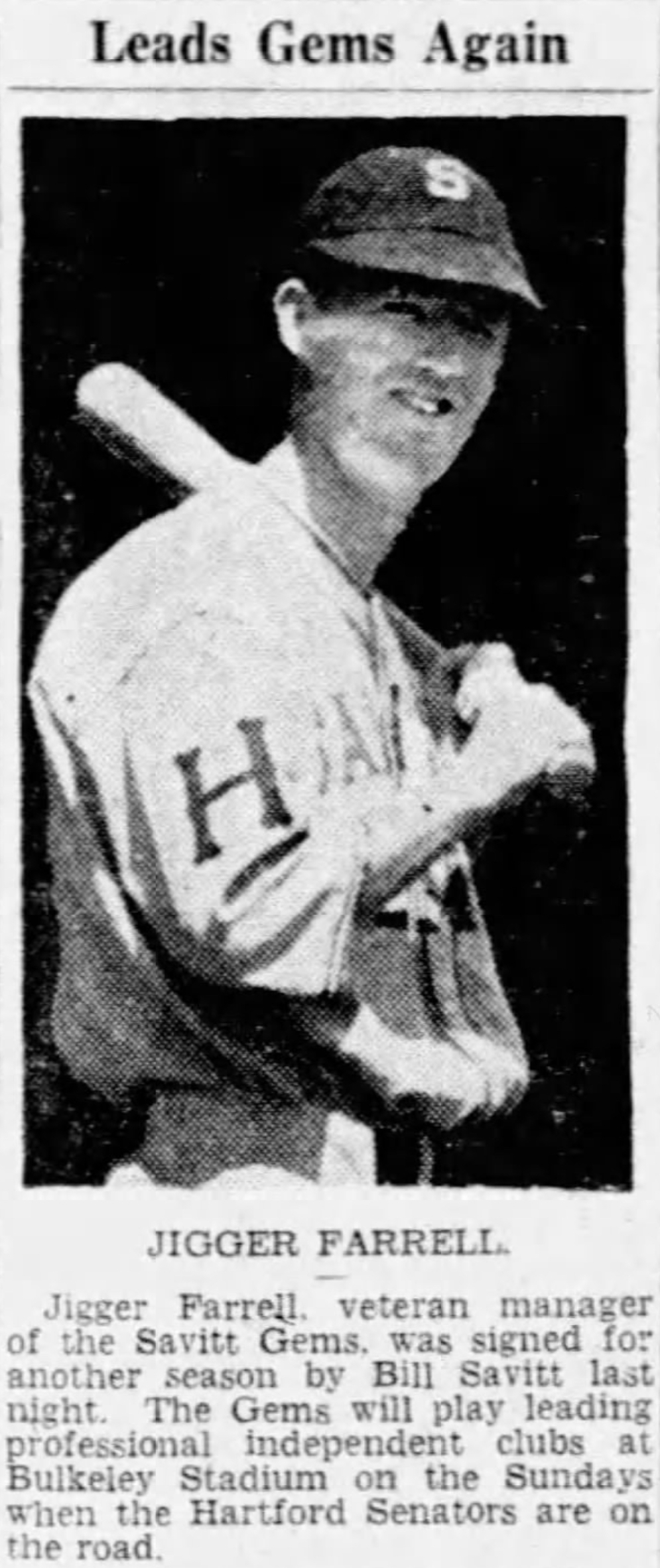

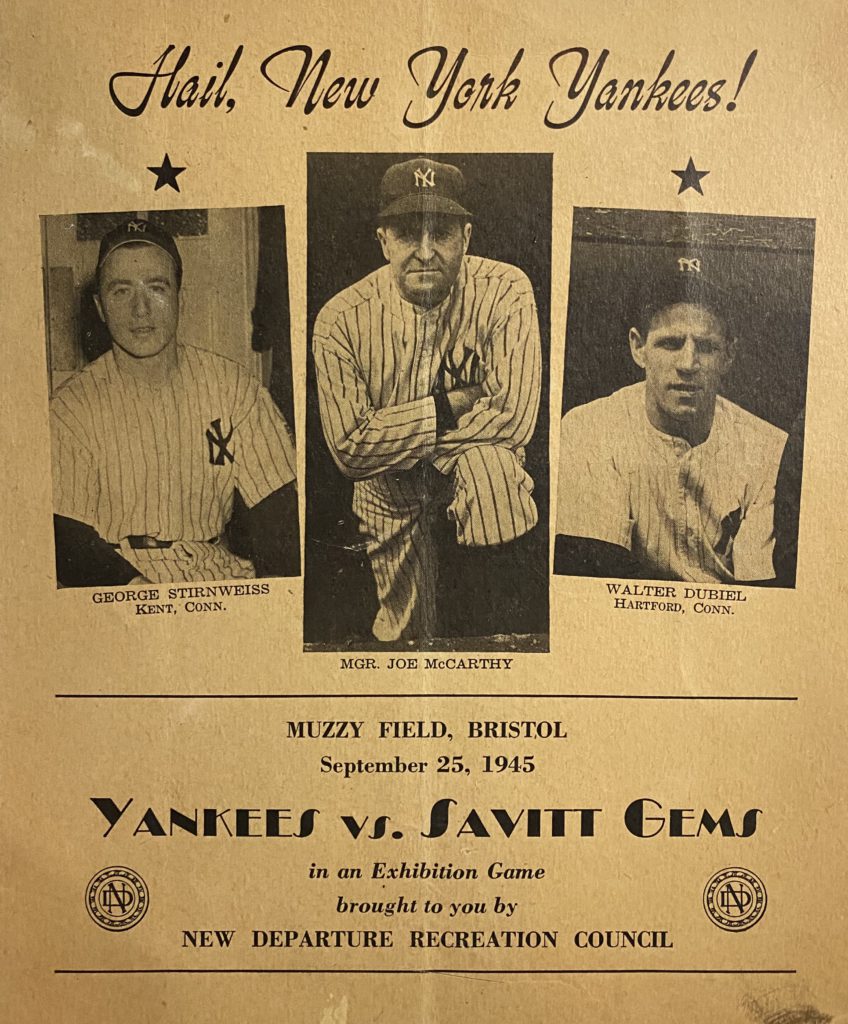

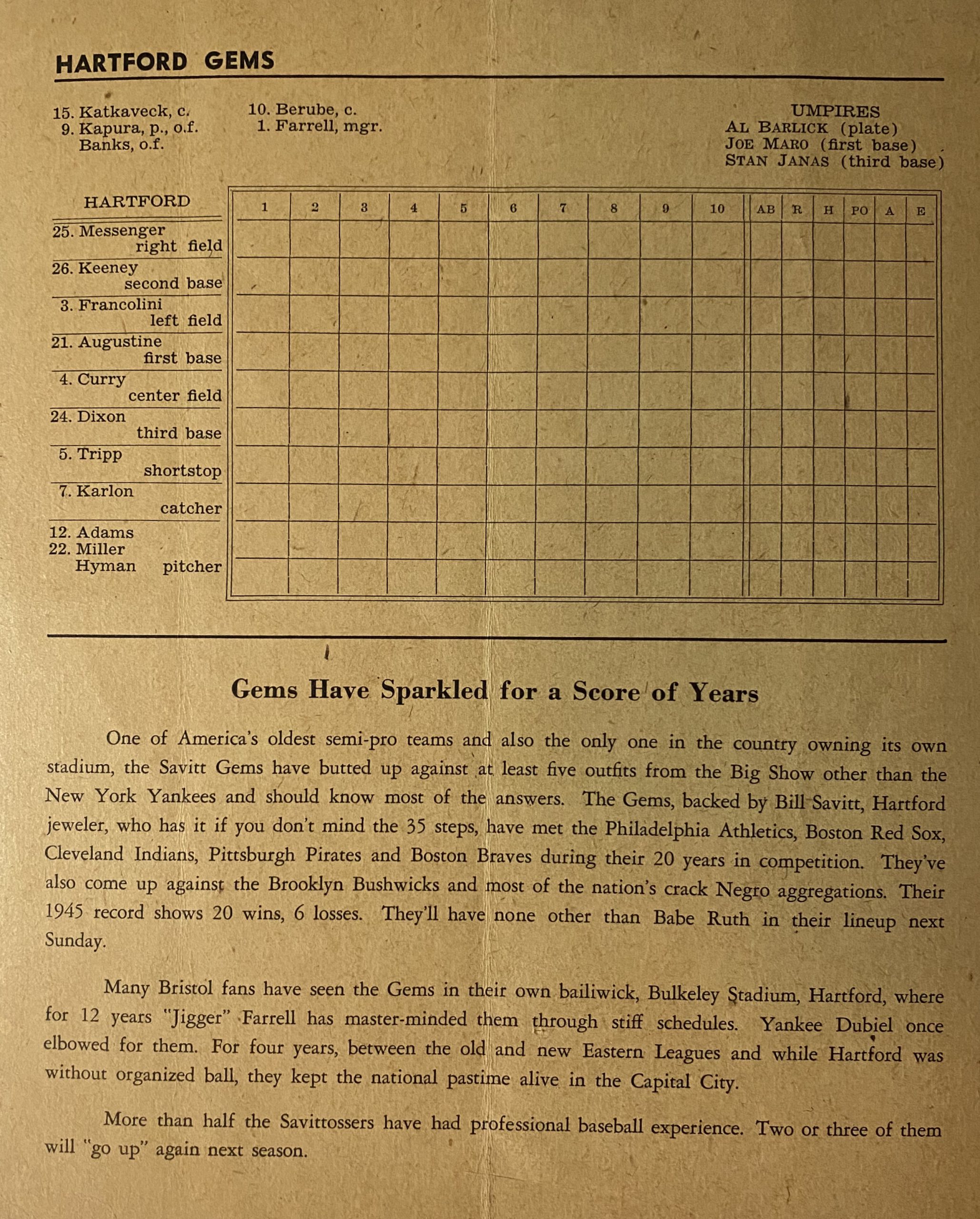

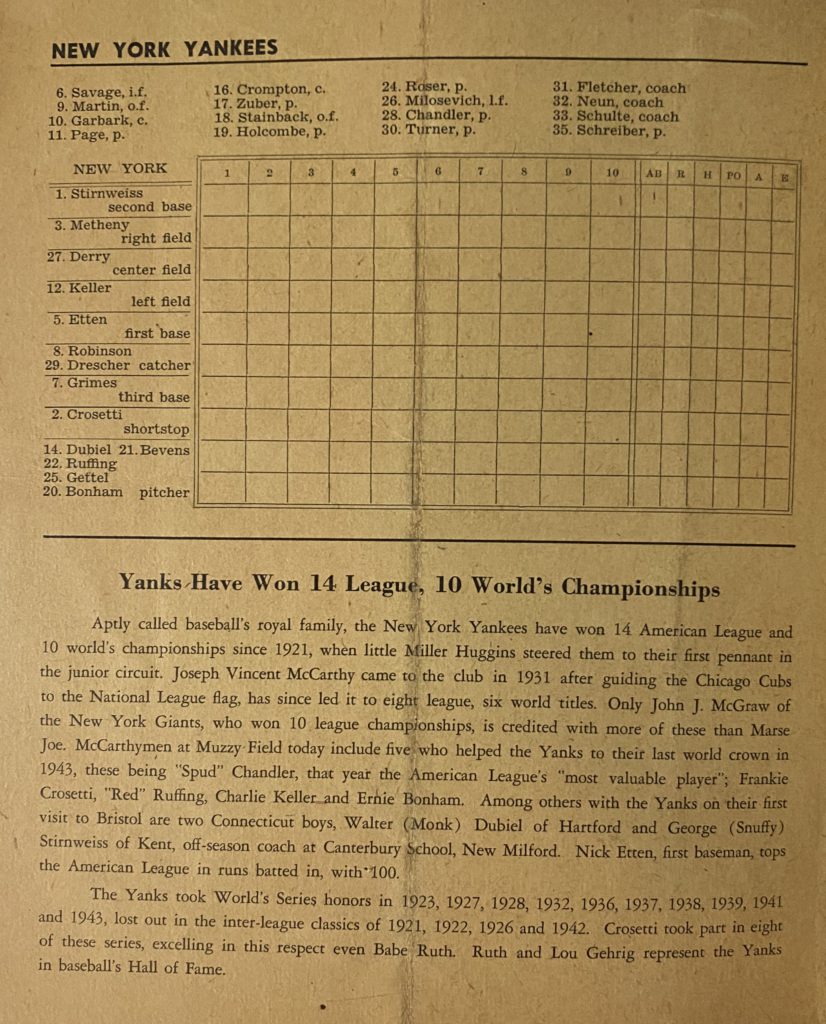

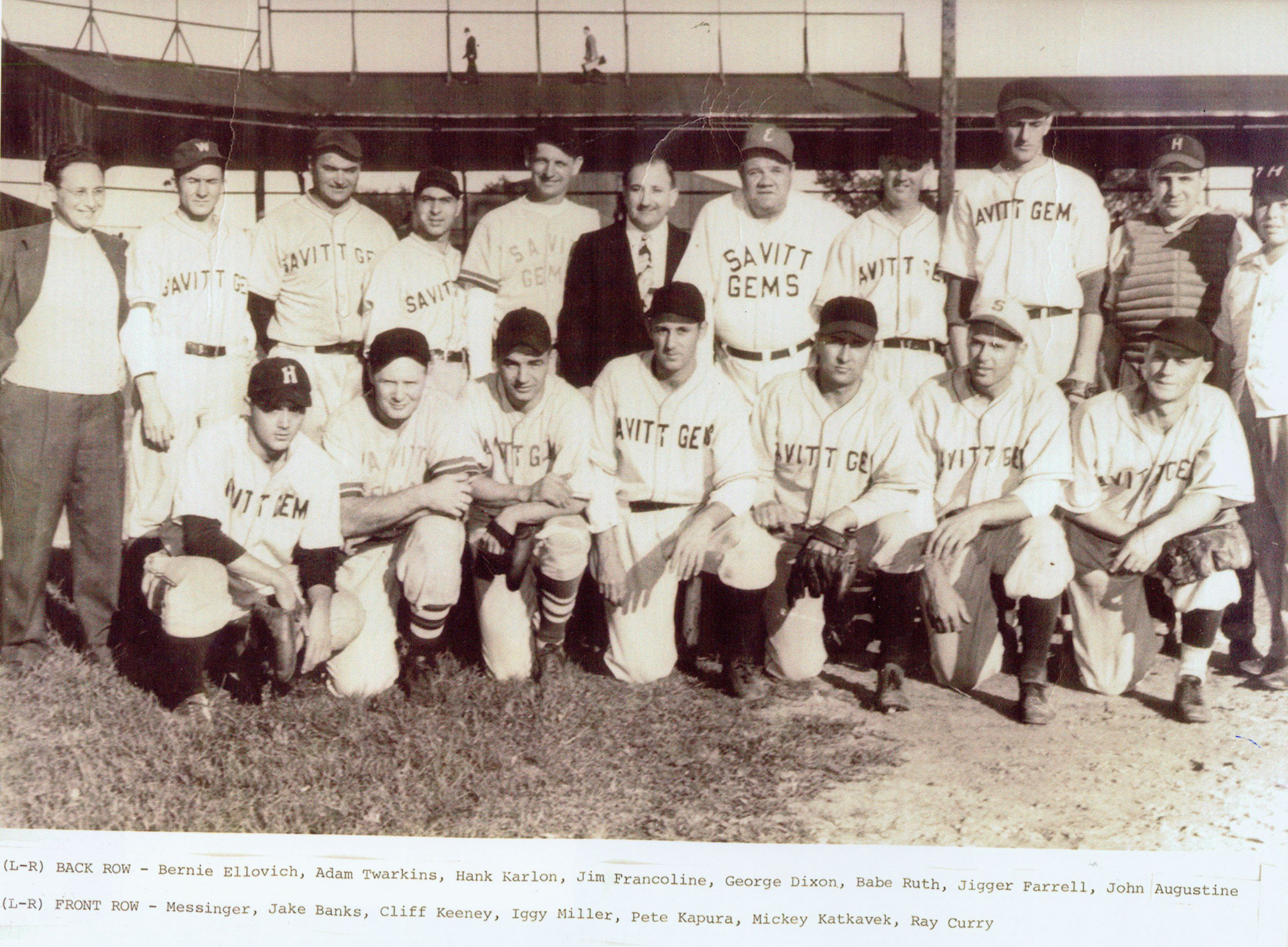

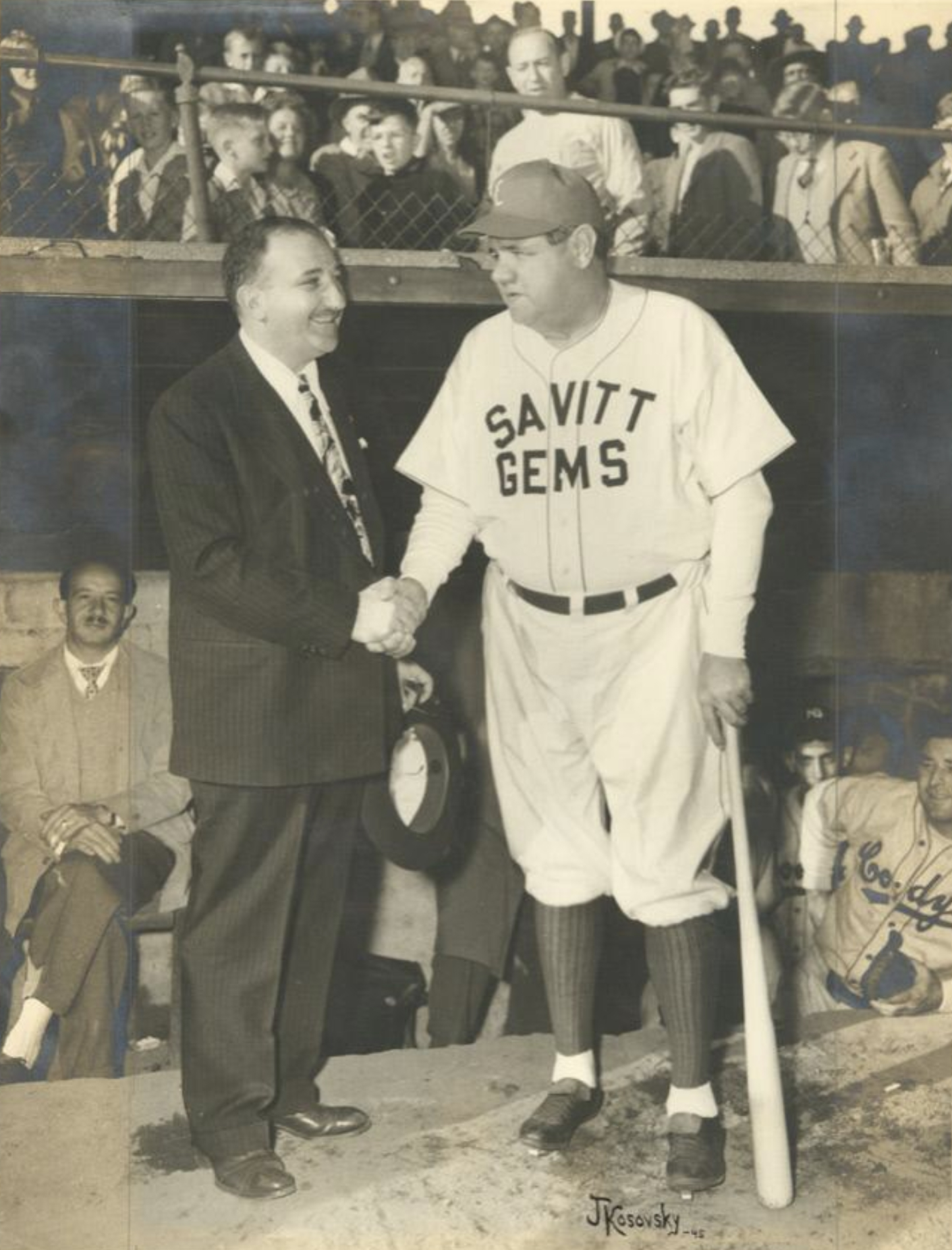

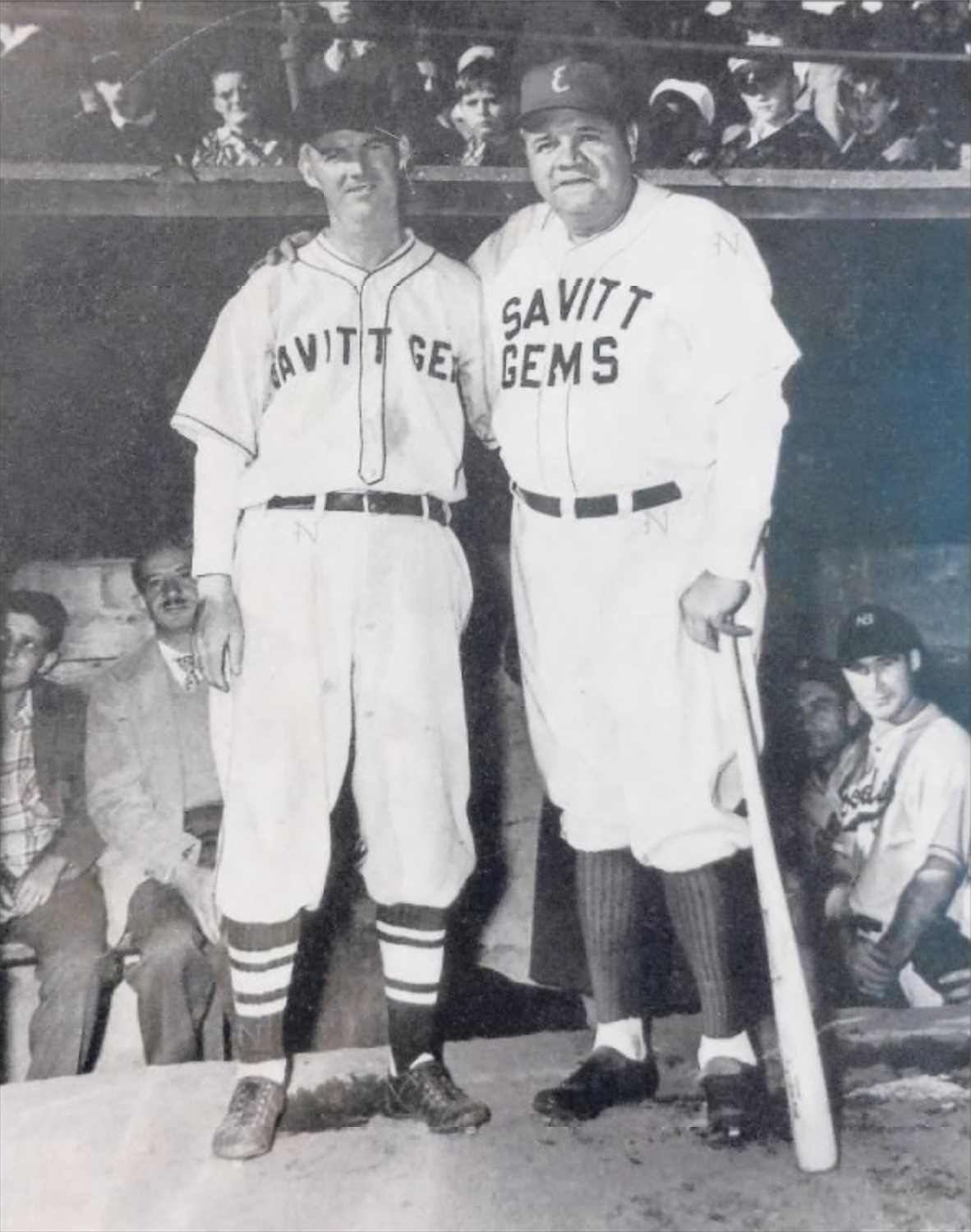

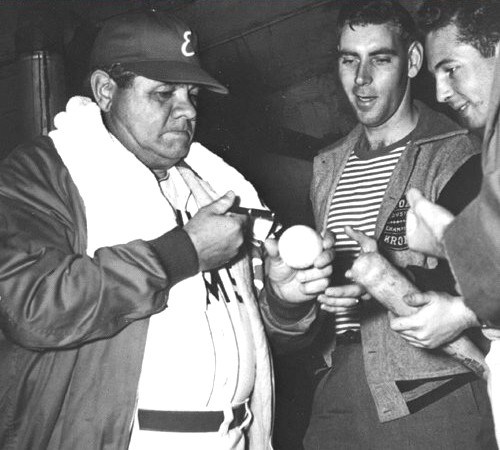

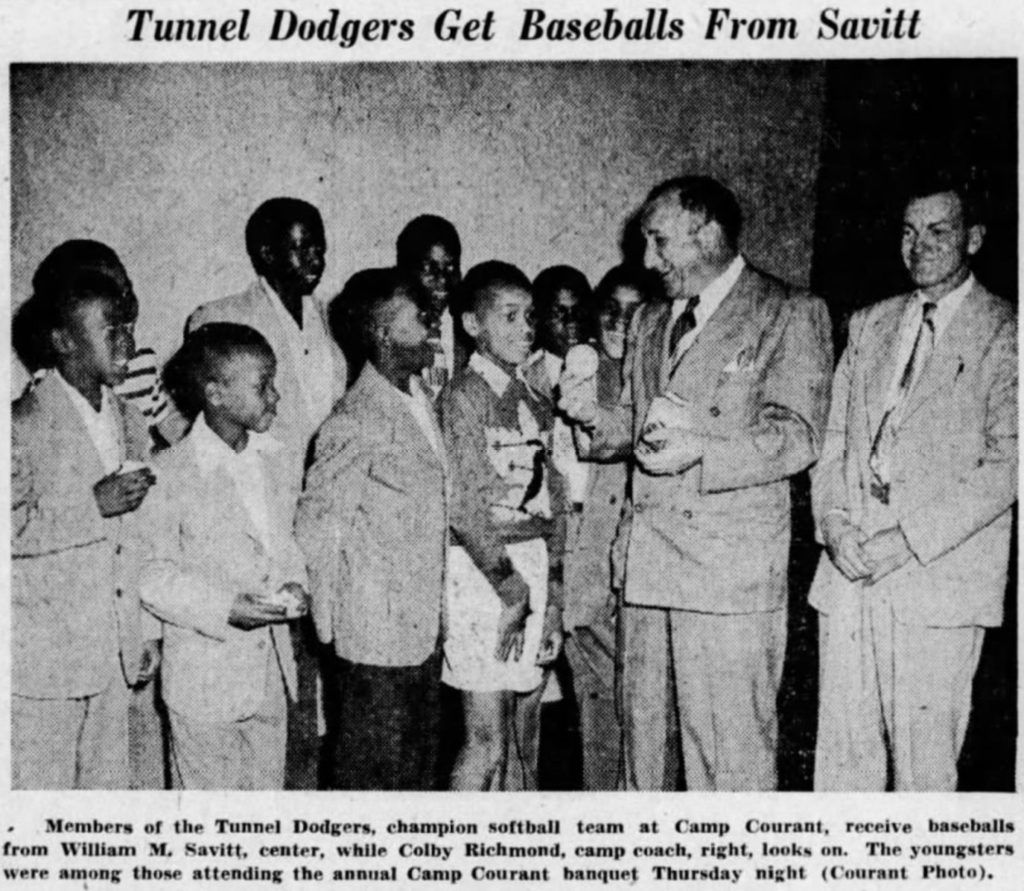

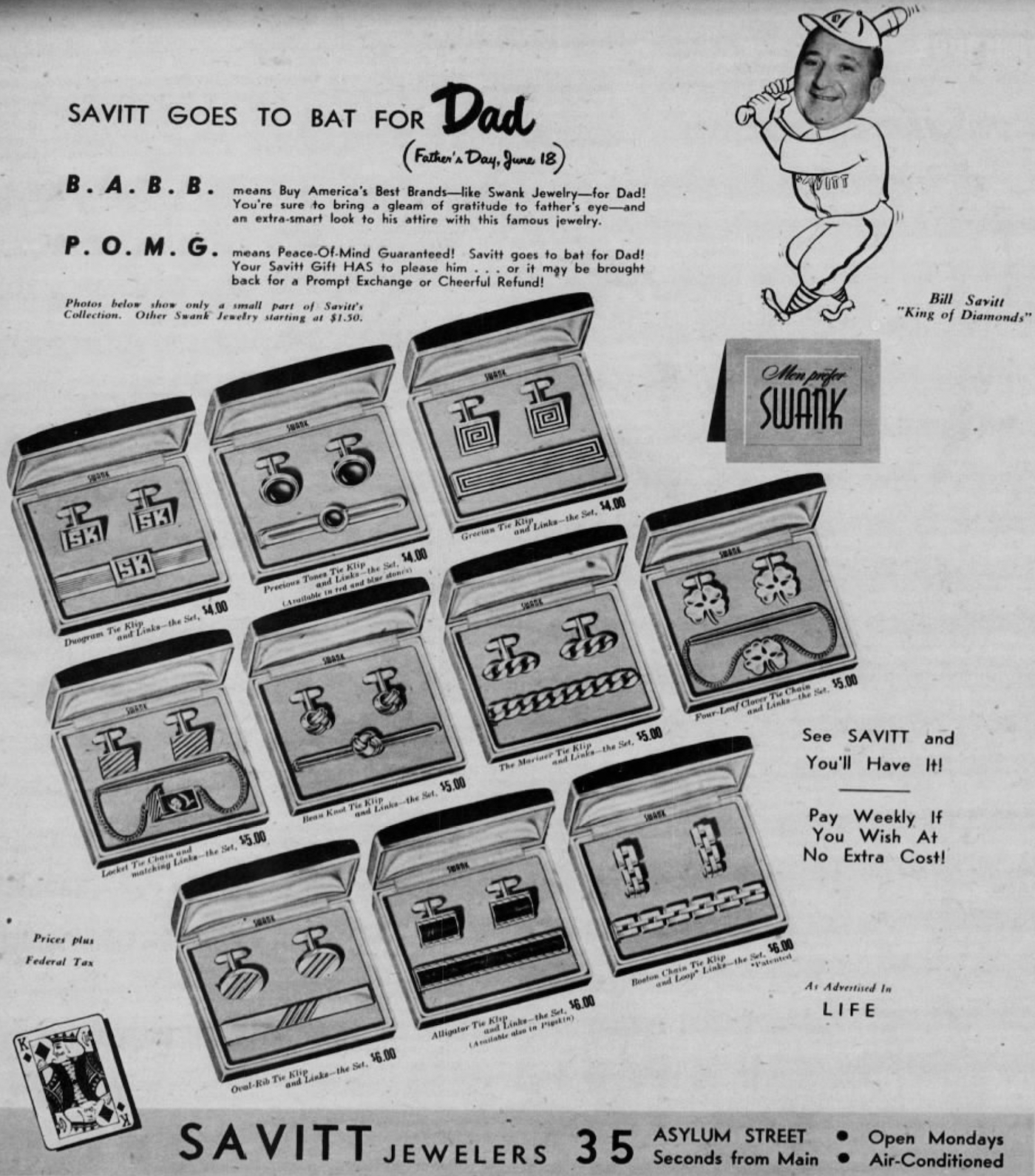

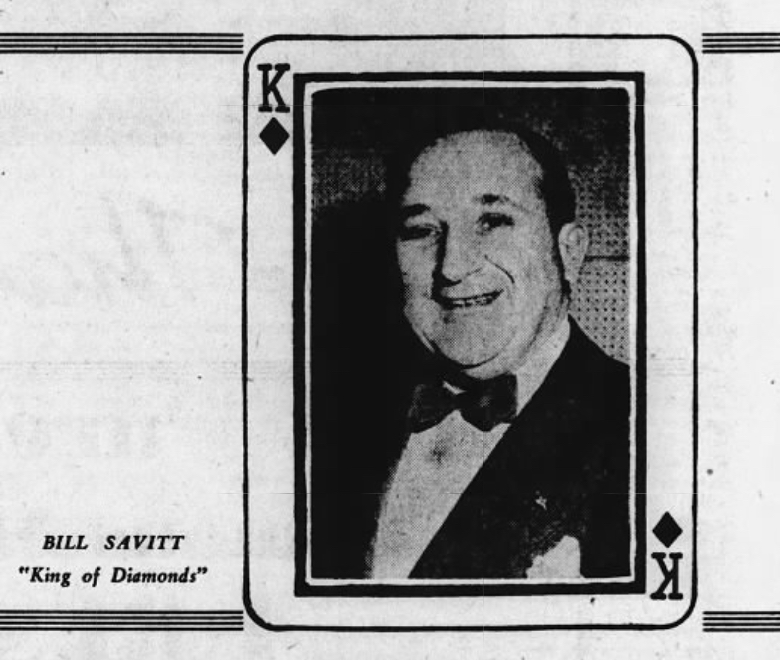

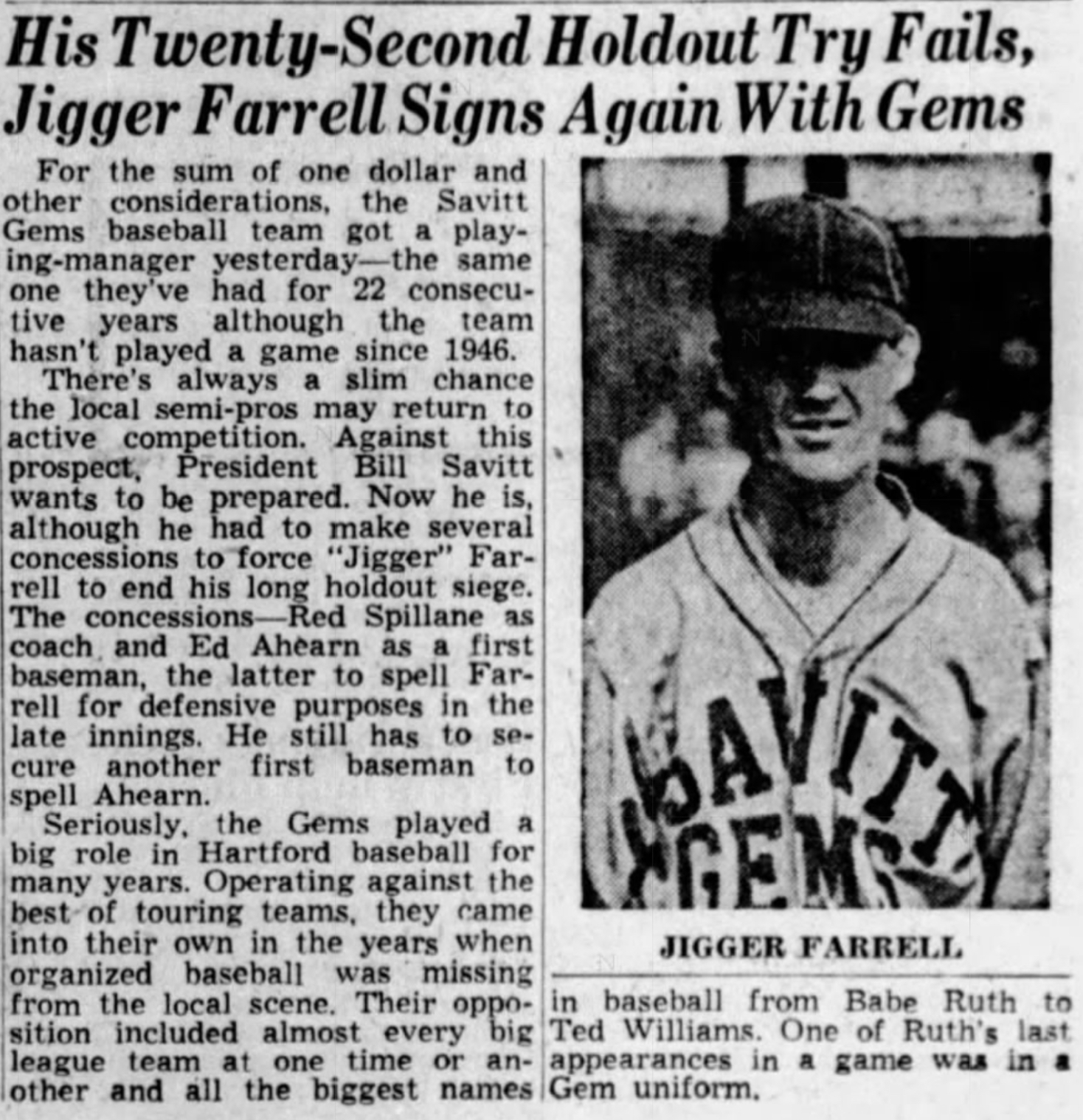

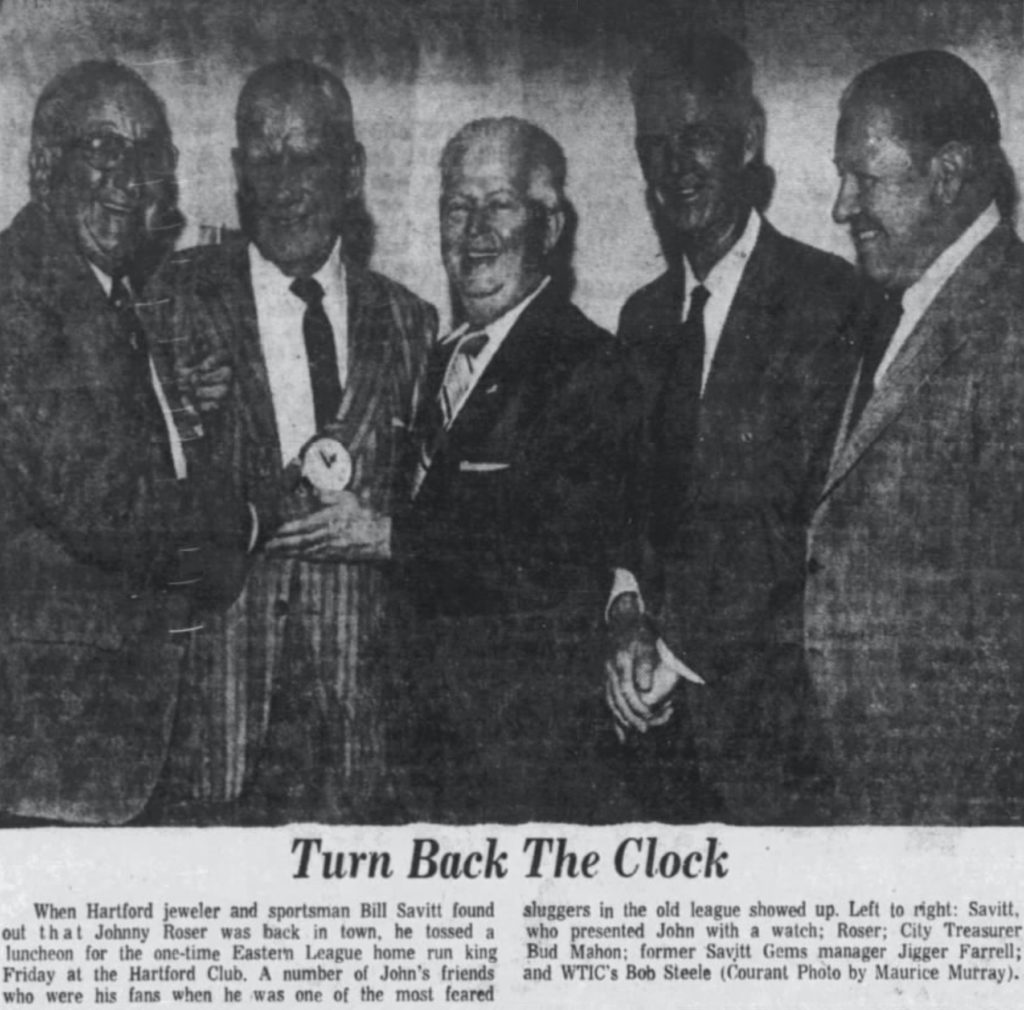

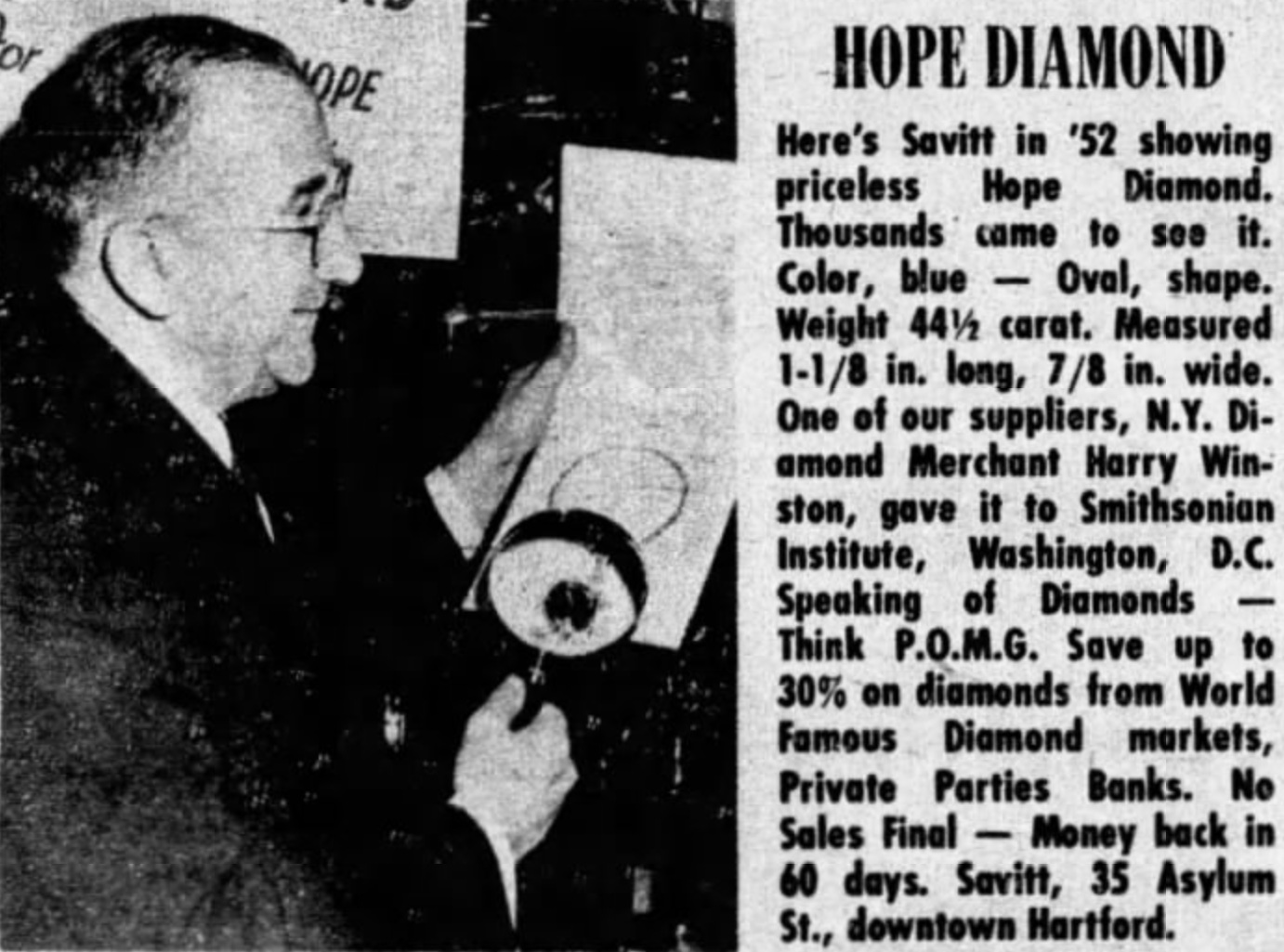

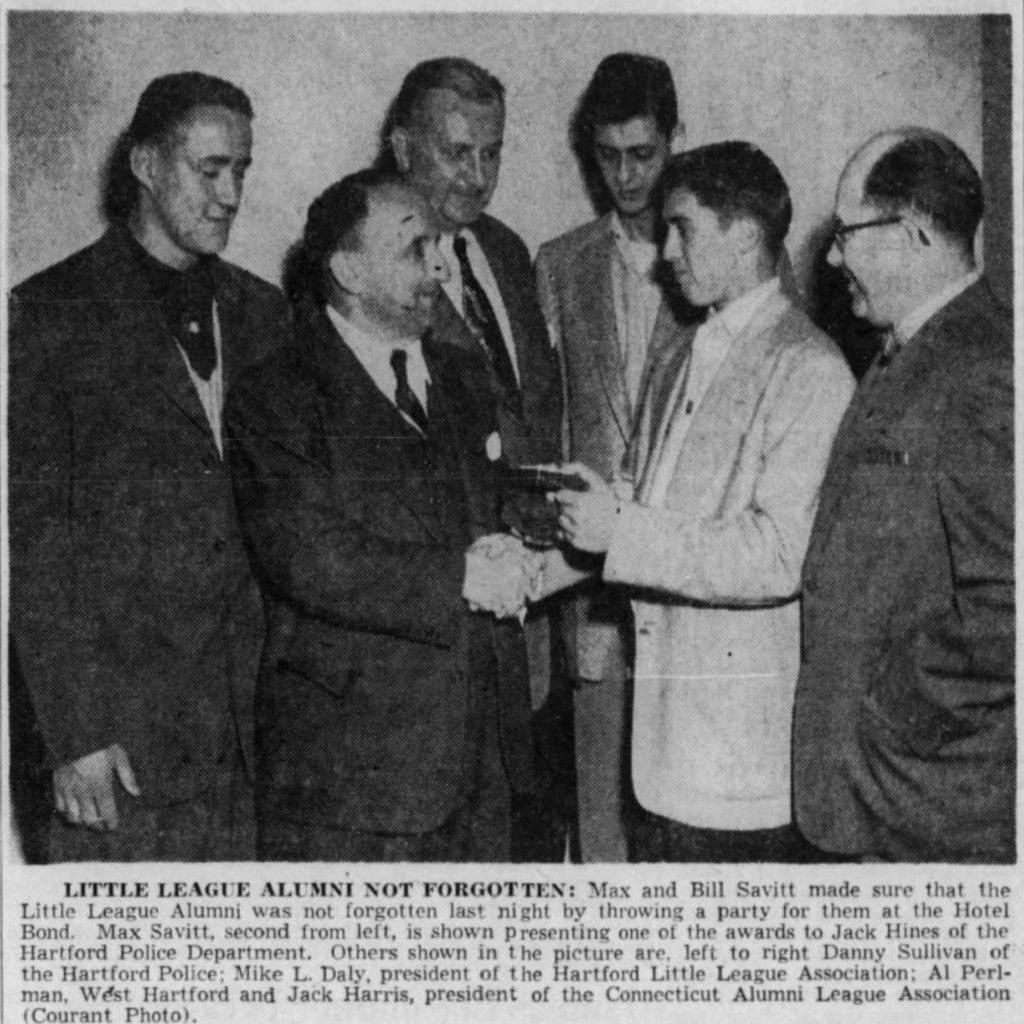

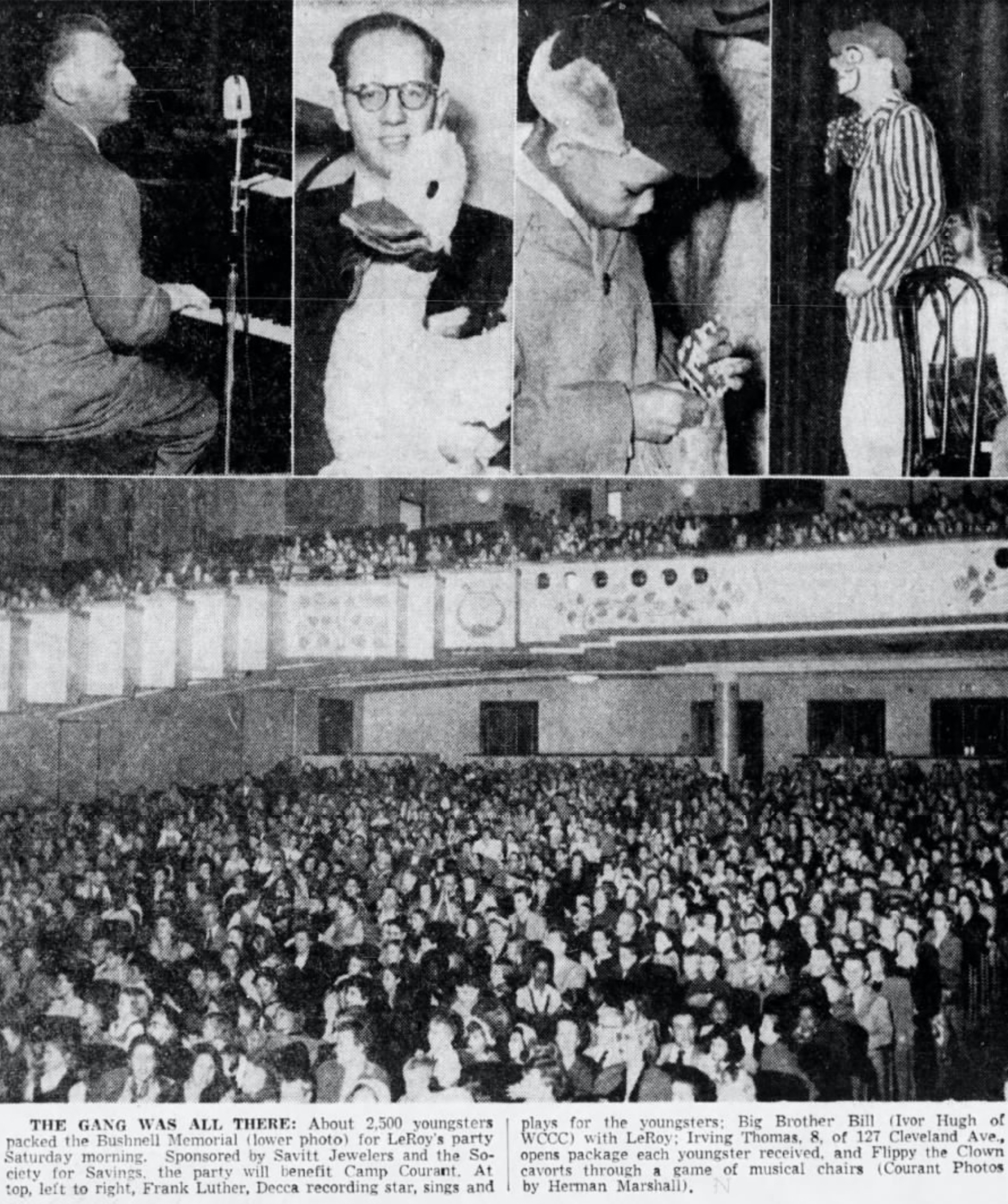

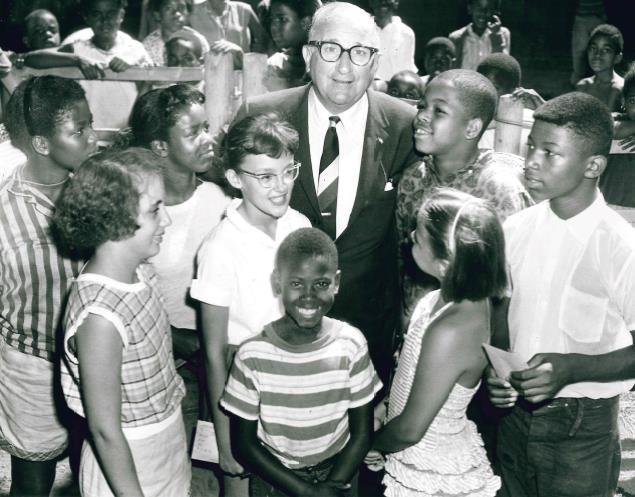

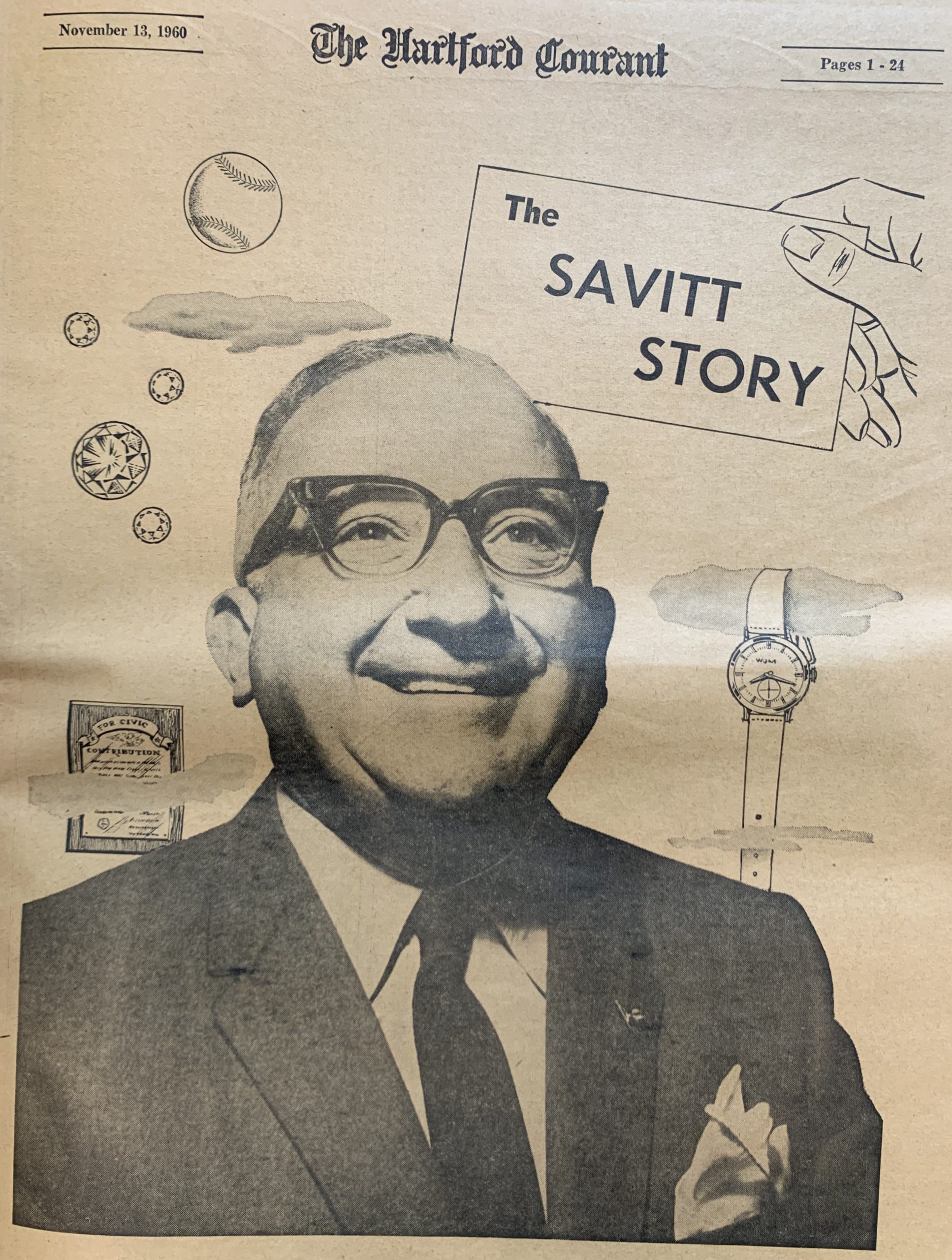

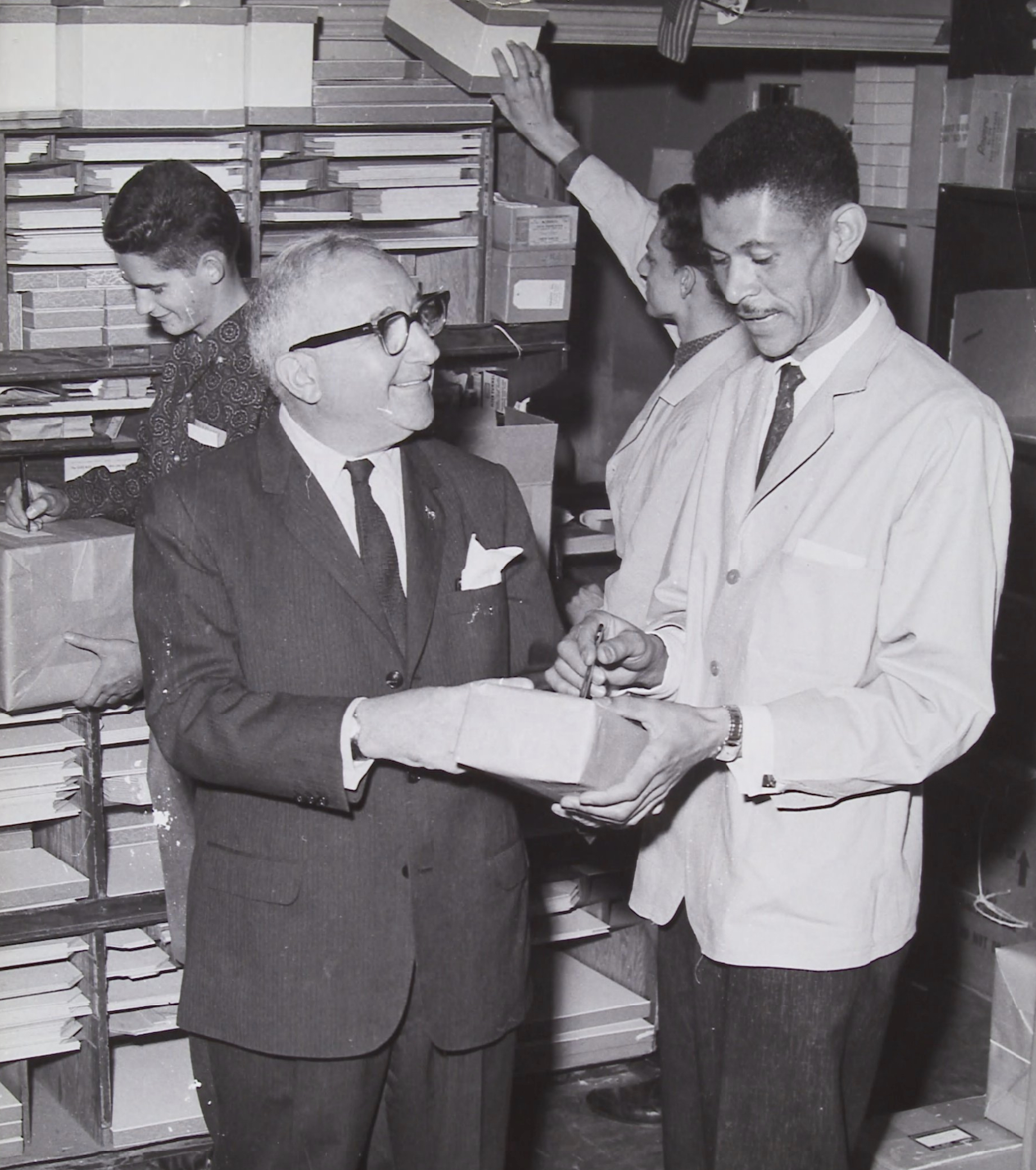

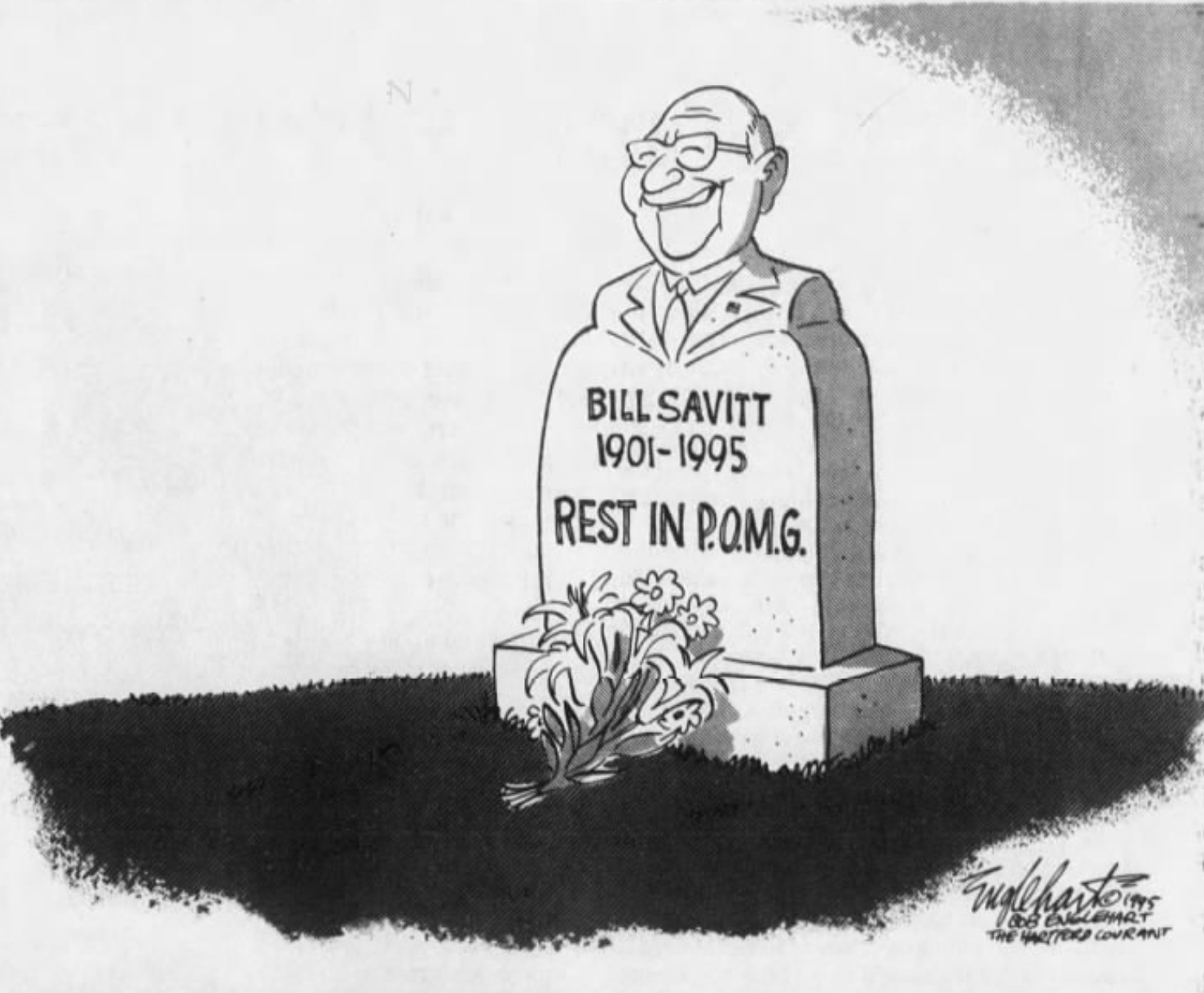

He spent three years in the minor leagues with the St. Louis Cardinals and the Philadelphia Phillies organizations. Piurek’s professional career concluded with the 1943 Utica Braves, managed by a 4-time World Series winner, Wally Schang. Piurek also played infield for several independent teams: Rutland Royals, Meriden Insilcos, Meriden Contelcos, West Haven Sailors, Waterbury Brasscos, Savitt Gems, Hartford Red Sox, Hartford Indians and New Britain Cremos. Among his peers on the diamond were big league stars Joe DiMaggio and Jimmy Piersall.

In 1943, Piurek accepted a teaching and coaching position at Plainville High School, where his teams won a state basketball championship and two state football titles. Then he moved on to West Haven High School as head baseball coach and remained there for 36 years. He was Athletic Director from 1965 to 1981 while also working as a history teacher. From 1948 to 1981, he was a professional scout for the Brooklyn Dodgers, Los Angeles Dodgers, Chicago White Sox, New York Yankees, San Francisco Giants and Seattle Mariners.

His coaching career at West Haven High School is nothing short of legendary. Piurek finished with an 526-115-2 overall record from 1945 to 1981. He was the first baseball coach in Connecticut history to achieve 500 victories. His clubs won two state championships (Class L in 1967 and Class LL in 1973) and finished runner-up twice (1955 and 1974). Under Piurek’s hard-nosed leadership, West Haven achieved 21 District League titles and a remarkable 34-game winning streak (1967-1968).

His coaching philosophy was grounded in fundamentals. West Haven Athletic Director Jon Capone, who played for Piurek and co-captained the 1973 title-winning team, recalled that, “Piurek was a stickler for the basic fundamentals of the game. He always said physical mistakes are excusable to a limit, but mental mistakes are never accepted.” Coach Piurek demanded excellence and precision from his players at all times, fostering the same discipline and focus key to his success.

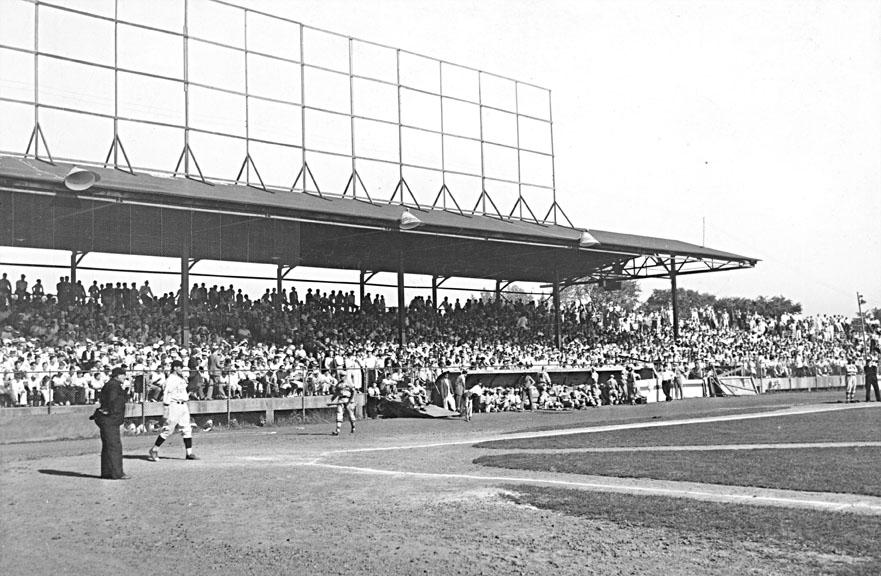

In addition to his accomplishments in baseball, Piurek’s football teams attained a 57-27-4 record. In 1948, West Haven High School football played before a record-breaking Thanksgiving Day crowd of 42,242 at the Yale Bowl against Hillhouse, a highlight in New England scholastic history. Piurek’s basketball teams accomplished a 114-59 record with eight state tournament appearances.

Yet his impact extended beyond scouting and coaching as an official and administrator. Piurek was president, commissioner and tournament chairperson for high school officiating in football, baseball, basketball, soccer and hockey. He helped organize the Connecticut High School Coaches Association and served as its second president. His devotion to local sports continued until his final days.

Piurek’s athletic legacy is enshrined in multiple halls of fame: the National Federation of High Schools Hall of Fame (1998), the Connecticut High School Coaches Association (1981), the Greater New Haven Diamond Club (1981), and West Haven High School itself (2000). He was also awarded High School Coach of the Year by the American Association of College Baseball Coaches (1967 and 1973) and the National Federation of State High School Associations (1968).

Piurek’s assistant coach and successor at West Haven High School, George Hanchette, stated, “Whitey had a knack of making the most out of every single minute at practice. He had it down to a science. If you couldn’t get the work done within two hours, you’d just be wasting time after that.” Piurek was ever focused on the present, never referring to past successes but emphasizing the importance of living in the moment.

Whitey Piurek’s contributions to West Haven High School were commemorated in 2004 when the school’s baseball field was named in his honor. His long-lasting influence on the school and community remains a point of pride for all who knew him. He passed away on December 3, 2009, at the age of 94, leaving behind an enduring legacy of excellence in coaching, sportsmanship and dedication to youth athletics. As one of Connecticut’s most accomplished and respected sports figures, Piurek’s life work continues to inspire.

Sources

1. Spiegel, Dan. “Hartford Kid Struck Out 25 But Never Got Chance at the Majors.” Hartford Courant, 7 Mar. 2014, www.courant.com/2014/03/07/hartford-kid-struck-out-25-but-never-got-chance-at-the-majors-2/. Accessed 4 Dec. 2024.

2. Lovelace, Leland. “Ex-Westies Coach Piurek Dies at 94.” New Haven Register, 18 Oct. 2017, www.nhregister.com/news/article/Ex-Westies-coach-Piurek-dies-at-94-11641164.php. Accessed 4 Dec. 2024.

3. Various news articles from New Haven Register, Record-Journal and Hartford Courant, Newspapers.com

4. Rutland Historical Society. Baseball in Rutland: The Rutland Royals. Rutland Historical Society. Retrieved December 6, 2024, from https://rutlandhistory.com/baseball-rutland-royals/